Winner take all science

Is it helpful for things to work this way?

By the early 1950s, it was known thanks to people like Miescher, Levene, and Chargaff that genes were carried by long polymers in the cell nucleus. It was also known that those polymers had a sugar-phosphate backbone and were composed of four different nucleobases—cytosine (C), guanine (G), adenine (A) and thymine (T)—and that there were always equal amounts of C and G and equal amounts of A and T.

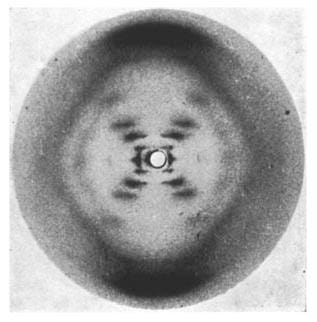

So we knew a lot about DNA. But we didn’t know the structure of it—what these polymers actually looked like. Many people were trying to figure this out including Wilkins, Franklin, Pauling, and Corey. Also working on it were Francis Crick and James Watson, who were worried that Pauling in particular would find the answer before them, so they rushed to find the answer. They—controversially—managed to get access to Photo 51 produced under Franklin’s supervision and were the first to publish the correct structure.

Crick and Watson are two of the most famous scientists of all time. And what they did was amazing and deserves to be celebrated. But still, arguably they are over-celebrated.

For one thing, many people mistakenly think they discovered DNA, rather than the structure of DNA.

For another, they had lots of help and helpful discussions with others. Wilkins even shared the Nobel but isn’t remembered as much. (Pauling won a different Nobel soon after.) Franklin sadly died before the Nobel was awarded, likely as a result of exposure to X-rays she encountered while making things like Photo 51. But Nobels can have a maximum of three winners, so some one had to miss out. This creates a huge nonlinearity in how much status one earns in terms of your perceived contribution.

Finally, there were lots of competitors. Imagine they didn’t get their hands on Photo 51 or took longer to find the answer, or just didn’t work on DNA at all. It’s certain that Pauling or Franklin or someone else would have published the true structure soon anyway. The marginal impact of their choosing to work on this problem is arguably not that big.

Natural Selection

When Darwin returned from the Beagle in 1836 at the age of 27 he already had the basic idea that living beings were adapted by natural selection. But he worried about controversy and gave priority to his geological research, so he didn’t publish his theory for more than 20 years. Then on June 18, 1858, he was startled to get a letter from Alfred Wallace that proposed essentially the same thing. Darwin immediately did two things:

He organized for a joint Darwin-Wallace paper which basically stapled together Wallace’s letter with some stuff Darwin was working on. This was read at the Linnaean Society on July 1, 1858.

Neither man attended since Darwin was in mourning and Wallace was still in Malaysia and as far as I can tell had no idea this was even happening.

Darwin decided that he must immediately-now-ASAP publish some version of his book, however imperfect. He took the notes he had been working on and rushed out a book, which appeared as The Origin of Species on November 24, 1859.

In the book, Darwin mentioned Wallace as coming to the same conclusion independently. In the 3rd edition, Darwin also noted that Patrick Matthew had anticipated the idea in 1831, and in the 4th edition, he gave credit to William Charles Wells for doing so in 1813.

Overall, this is a nice story. Darwin comes off as a good egg and Wallace always defended Darwin and shunned fame despite being given every possible award and honor. But still—you learned about Darwin as a child, maybe learned about Wallace later on but probably never heard of Matthew or Wells.

Again, it’s interesting to speculate: How much Darwin accelerated the theory of natural selection? My guess is quite a bit—it would have taken Wallace a while to publish his results without Darwin, and even if he did, they might have gone under-appreciated like Matthew and Wells’ ideas did. But still, it was going to happen eventually. (It would have been better if he didn’t wait 22 years!)

General Relativity

Einstein did many things but most people say his greatest achievement was general relativity. But most don’t know that there’s an ongoing debate about the priority of that theory.

When working on it in 1915, Einstein was in frequent communication with Hilbert, who was working on something similar. On November 20, Hilbert submitted a paper with field equations similar to those Einstein presented on November 25.

There was a bit of scuffling about the priority of this discovery, with some talk on both sides of “nostrification”. But Einstein and Hilbert didn’t want any public dispute and so quickly settled things.

Still, there’s an unbelievably convoluted history of what information was shared in letters between them, what revisions were made to their papers at what time, who claimed priority for what, and even if Einstein was capable of understanding the mathematics in Hilbert’s work. The debate continues today. For example, Corry et al. (1997) found the original printer’s proofs of Hilbert’s 1915 paper and argued these don’t anticipate Einstein. But then Winterberg (2014) suggests that a crucial part of that paper was cut off, and speculates this was “a crude attempt by some unknown individual to falsify the historical record”.

But… do we care if Hilbert presented his equations five days before Einstein? The consensus seems to be that Einstein made the larger contribution, but both had novel insights and benefited from each other. Don’t we want them to collaborate? Isn’t that the best way to make progress?

The trenches

Similar things happen every day in the trenches of workaday science. The idea of there being a single person/group that is first just doesn’t match very well with reality and has weird effects.

In biology today many are paranoid about being scooped, which makes people cagey when talking about their work. Many avoid presenting posters before publication and some are even intentionally vague in grant proposals. This paranoia happens even inside single labs, with grad students and postdocs suspicious of each other. (It must be said that the rise of bioRxiv has helped here, in allowing people to put their “stamp” on something more quickly.)

Or say two groups send papers with the same idea to the same computer science conference. What happens? Well, reviewing is known—via both universal griping and randomized trials—to be pretty random. If a typical accepted paper were sent through peer review again, it would be rejected around 50% of the time.

So there’s a good chance one paper will be accepted and the other rejected. Then the rejected group is sort of screwed—if they submit their paper somewhere else, the other group’s paper will count as prior work.

Or say you’re a company and you want to bring a drug to market. If another company gets a drug approved before you, it causes big problems. First, if doctors get used to prescribing one drug, you’ll have a hard of a time convincing them to switch. Beyond that, as time goes on it becomes harder to convince the FDA to approve new drugs. The reason is that the first drug for a given indication just needs to prove superior safety and efficacy compared to the current “standard of care”. But once that drug becomes the standard of care, every other drug trial must compare to it, which is more difficult.

Drug companies are obsessed with figuring out what stage other companies are at with drug approvals. If you get approved first, then not only do you have the first-mover advantage, but you make it more expensive for anyone else to get a drug approved for the same condition since they must compare to yours and show their drug is at least as effective. Tons of resources are poured into developing drugs, only to be dropped when another company gets an approval.

Small companies often do a (cheaper) phase-one trial of a drug and then use that data to raise more money. But once some other company has a drug approved, potential investors know that the later-phase trials will be more expensive, and the FDA might decide they don’t want any more drugs for that condition. The first company to bring a drug to market sort of pulls the ladder up after them. In the end, lots of people end up taking drug A rather than drug B just because company A happened to start their trials earlier.

Why are things like this?

So why is science so winner take all? I think that several different forces act in parallel.

First, winner take all dynamics create many good incentives. Encouraging people to move fast might make people a little sloppy and encourage infighting, but we also want people to go fast! It’s often good to have multiple people working on important problems since any single group might fail. And if you’re constantly getting scooped, you’ll probably switch to a less crowded niche, which is also good in terms of reducing redundant effort.

However, the incentives aren’t perfect. Say you’re guaranteed to make a Momentous Discovery in a year. If I compete with you, I’ve got a 50% chance of beating you by a week. Alternatively, I can work on some other problem that no one else could solve but will be seen as only one-tenth as Important. It’s probably better for society if I work on the other problem, but my expected value is 5x higher if I compete with you.

Second, people are lazy. When writing a paper and choosing citations, most people don’t really care about fairness—they just want to quickly put in some citations and go get coffee. Just think about it—to truly get citations right, authors would have to trace the ancestor tree for every idea they use, which would be a crazy burden. So most just copy whatever citations other people use for the same idea.

If that doesn’t convince you, I also have much stronger evidence for laziness. Go take a random paper and see how it describes the papers it cites. Then, go read the cited papers. Half the time, the descriptions are completely incorrect. It seems crazy to me that people don’t talk about this more, given that citations are the lifeblood of academia, but I guess it’s a kind of Gell-Mann amnesia—everyone notices that the descriptions of their own papers are totally wrong, but merrily assumes the other descriptions are still OK.

Third, just like all other human activities, there are natural status hierarchies. Say two people make the same discovery simultaneously. If the less-famous person is giving a talk and failed to mention the famous person, someone will instantly chide them. The same is not true for the famous person. Even if the famous person makes a point of mentioning the other person—which many do—people are still more likely to remember and cite Dr. Famous.

Fourth, people like good narratives. A tangled history of dozens of people making little contributions and sending letters back and forth is not a good story. And there are good reasons for having good narratives. For example, in science education, it’s much easier to digest ideas if they are attached to a good story. It’s not crazy to sacrifice some fairness to help educate the next generation.

Fifth, organizations like the FDA are kind of inscrutable. Their stated mission is basically “protect public health by making sure drugs are effective and safe”. That sounds nice, but the real world is full of difficult tradeoffs and I can’t understand what framework the FDA is using to navigate them, or why some of the rules exist. How do they prioritize scientific progress vs. controlling costs vs. addressing rare diseases vs. economic growth? Are there institutional constraints? Why has the FDA gotten more stingy about approvals in recent years? Companies pay the FDA huge amounts for applications, so it wouldn’t seem to be a cost-saving measure, but maybe they’re just overwhelmed?

People in industry don’t generally seem to worry about why—they just try to clarify what the FDA wants and then give it to them. Ex-FDA employees are highly valued for their insight and connections, which is understandable but also disturbing when you think about it.

Finally, good incentive schemes are hard. After all, a lot of the same dynamics in science also happen in normal capitalism. Say you and I are both building social networks. They will equally good, but due to network effects, one will eventually take over the world and the other will go bankrupt. Likely we’ll both invest tons of resources competing with each other even if this doesn’t benefit the consumer. So this kind of thing isn’t unique to science.

But I think things are worse with science because you can’t compete on “quality” in the same way. I can launch a better social network after you and still win. But say you and I make the same discovery. You rush out a poorly written paper, while I take a few months to write some masterpiece that conveys much more insight and can be read with 1/4 the effort. You will still get most of the credit—even if I manage to publish my paper people will likely take the insights and attribute them to you.

And imagine we somehow found a way to drive credit equally for independent discoveries. This might make things worse. You might have heard an argument against minimum prices for ridesharing services: When per-ride prices go up, more drivers enter the market. This leads to drivers sitting idle for longer until average earnings are much the same as before. So riders pay higher prices, more resources are wasted, with little impact on hourly earnings for drivers.

The same thing might happen if we gave out equal credit for independent discoveries. In theory, more and more people work start working on the problem until the expected reward was down to that of normal boring problems. This could mean even more redundant effort than we have now.

Despite all that, I still think that one major reason things are like this is that we just aren’t trying that hard.

I don’t claim to have any kind of ultimate solution. I just think people are always strangely uninterested in innovating with social systems. Like, here’s an idea that’s so simple it seems stupid to even write it down. But if the goal of science prizes is to accelerate scientific progress why don’t we have a prize that… measures how much someone accelerated scientific progress?

Currently, prizes tend to look at who is first to produce an idea that has high impact. Those are good, but they aren’t exactly the same as maximizing progress. Say that person A makes a Miracle Discovery that 20 other people were on the verge of making, while person B makes a Decently Important Discovery that no one else would have found for 100 years. Is it crazy to give the prize to person B?

To maximize progress, we should incentivize behavior on the margin. In principle, the best way to measure that is to try to gauge what would have happened without the person in question. In a counterfactual world where A or B didn’t do their work, how different would the world look today?

Of course, you might object that measuring this would require lots of subjective judgment calls. True. But current prizes already involve lots of subjective judgment calls. It’s not obvious this would be much worse.

Thank you SO MUCH! I never understood why Watson and Crick were so worshiped. They didn't discover DNA, they didn't discover that it was life's code, they didn't figure out how it worked. They were the kings of PR.

Hello Dyno,

I have been reading your substack for a while now and I have no idea what it is about, what you do, who you are...

Today I decided I was going to support it... only to find a message I somehow never noticed before: dynomight is unsupported. Crazy.

Your writing blows my mind most of the time. Thanks a lot and lots of love.