Optimizing tea: An N=4 experiment

what brewing temperature is best?

Tea is a little-known beverage, consumed for flavor or sometimes for conjectured effects as a stimulant. It’s made by submerging the leaves of C. Sinensis in hot water. But how hot should the water be?

To resolve this, I brewed the same tea at four different temperatures, brought them all to a uniform serving temperature, and then had four subjects rate them along four dimensions.

Subjects

Subject A is an experienced tea drinker, exclusively of black tea w/ lots of milk and sugar.

Subject B is also an experienced tea drinker, mostly of black tea w/ lots of milk and sugar. In recent years, Subject B has been pressured by Subject D to try other teas. Subject B likes fancy black tea and claims to like fancy oolong, but will not drink green tea.

Subject C is similar to Subject A.

Subject D likes all kinds of tea, derives a large fraction of their joy in life from tea, and is world’s preeminent existential angst + science blogger.

Tea and brewing

For a tea that was as “normal” as possible, I used pyramidal bags of PG Tips tea (Lipton Teas and Infusions, Trafford Park Rd., Trafford Park, Stretford, Manchester M17 1NH, UK).

I brewed it according to the instructions on the box, by submerging one bag in 250ml of water for 2.5 minutes. I did four brews with water at temperatures ranging from 79°C to 100°C (174.2°F to 212°F). To keep the temperature roughly constant while brewing, I did it in a Pyrex measuring cup (Corning Inc., 1 Riverfront Plaza, Corning, New York, 14831, USA) sitting in a pan of hot water on the stove.

After brewing, I poured the tea into four identical mugs with the brew temperature written on the bottom with a Sharpie Pro marker (Newell Brands, 5 Concourse Pkwy Atlanta, GA 30328, USA). Readers interested in replicating this experiment may note that those written temperatures still persist on the mugs today, three months later. The cups were dark red, making it impossible to see any difference in the teas.

After brewing, I put all the mugs in a pan of hot water until they converged to 80°C, so they were served at the same temperature.

Serving

I shuffled the mugs and placed them on a table in a random order. I then asked the subjects to taste from each mug and rate the teas for:

“Aroma”

“Flavor”

“Strength”

“Goodness”

Each rating was to be on a 1-5 scale, with 1=bad and 5=good.

Subjects A, B, and C had no knowledge of how the different teas were brewed. Subject D was aware, but was blinded as to which tea was in which mug.

During taste evaluation, Subjects A and C remorselessly pestered Subject D with questions about how a tea strength can be “good” or “bad”. Subject D rejected these questions on the grounds that “good” cannot be meaningfully reduced to other words and urged Subjects A and C to review Wittgenstein’s concept of meaning as use, etc. Subject B questioned the value of these discussions.

After ratings were complete, I poured tea out of all the cups until 100 ml remained in each, added around 1 gram (1/4 tsp) of sugar, and heated them back up to 80°C. I then re-shuffled the cups and presented them for a second round of ratings.

Results

For a single summary, I somewhat arbitrarily combined the four ratings into a “quality” score, defined as

(Quality) = 0.1 × (Aroma) + 0.3 × (Flavor) + 0.1 × (Strength) + 0.5 × (Goodness).

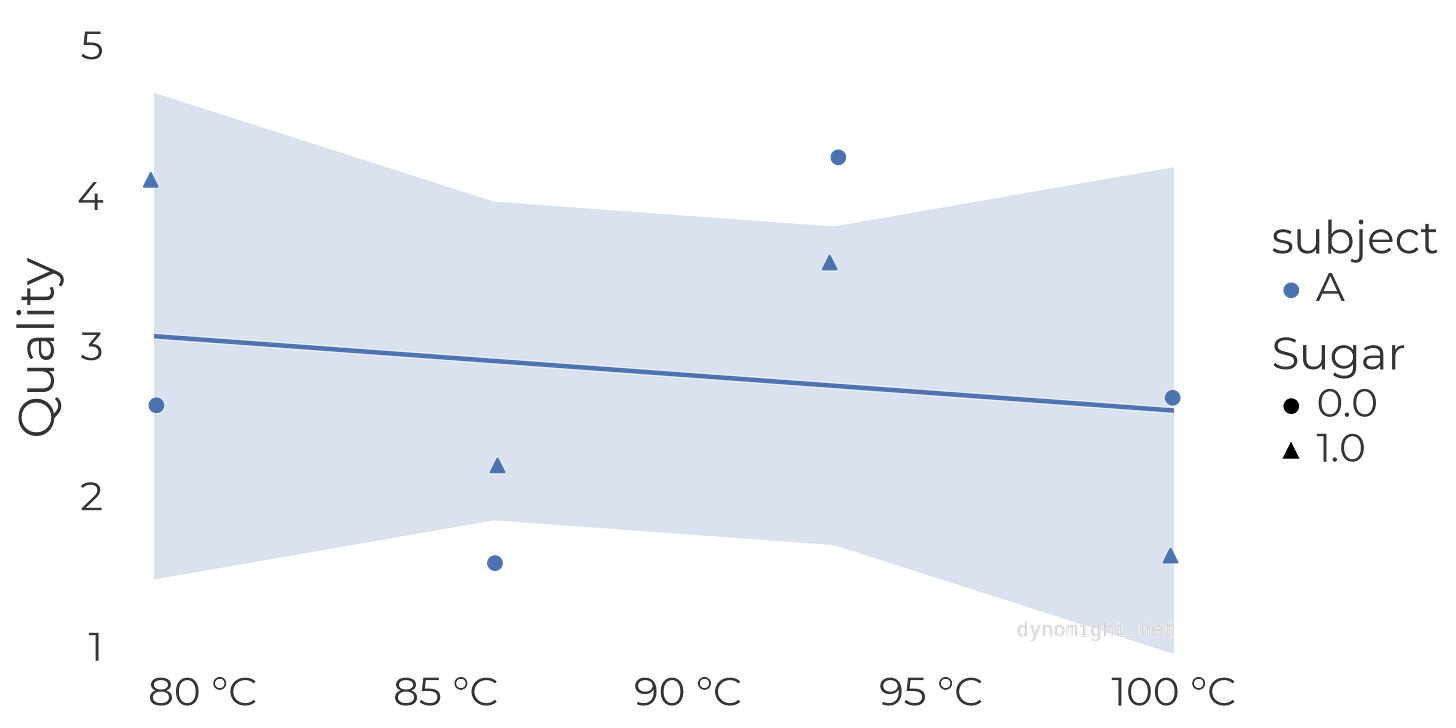

Here is the data for Subject A, along with a linear fit for quality as a function of brewing temperature. Broadly speaking, A liked everything, but showed weak evidence of any trend.

And here is the same for Subject B, who apparently hated everything.

Here is the same for Subject C, who liked everything, but showed very weak evidence of any trend.

And here is the same for Subject D. This shows extremely strong evidence of a negative trend. But, again, while blinded to the order, this subject was aware of the brewing protocol.

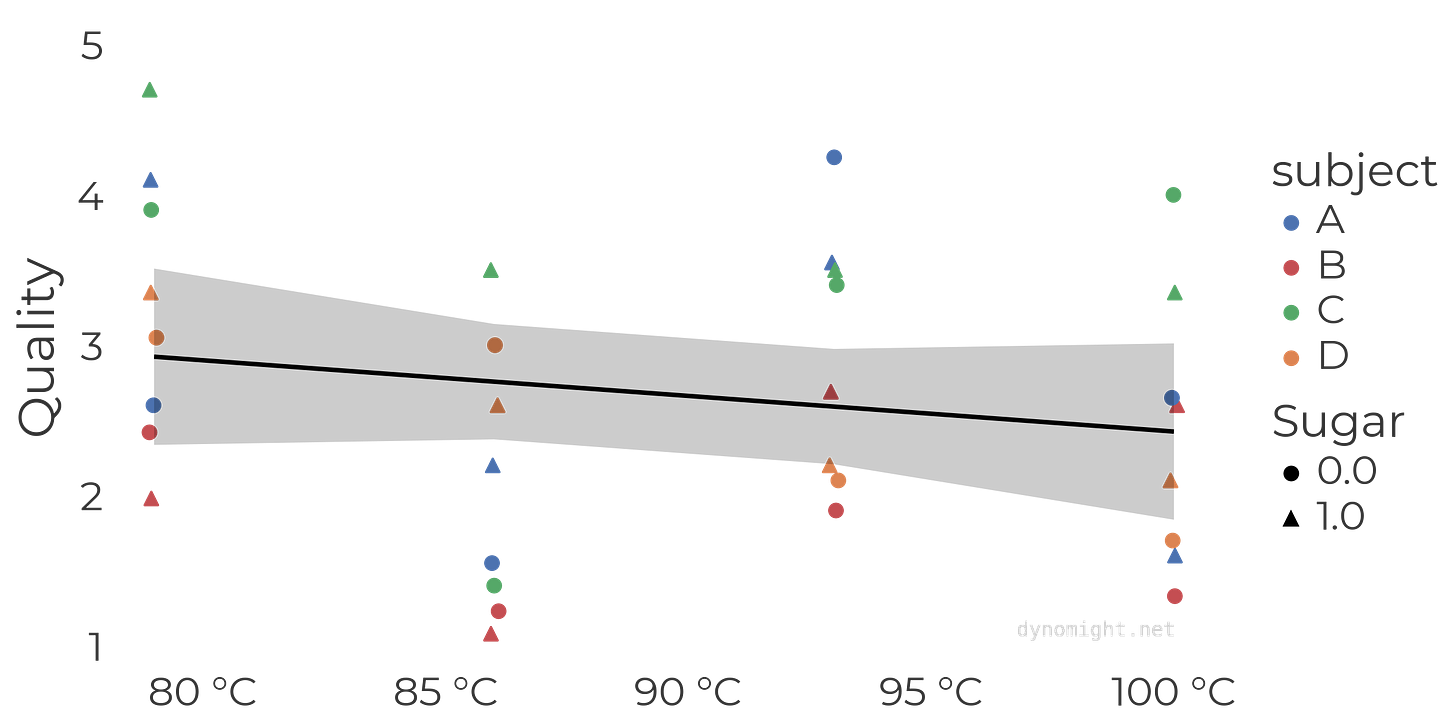

Finally, here are the results combining data from all subjects. This shows a mild trend, driven mostly by Subject D.

Thoughts

This experiment provides very weak evidence that you might be brewing your tea too hot. Mostly, it just proves that Subject D thinks lower-middle tier black tea tastes better when brewed cooler. I already knew that.

There are a lot of other dimensions to explore, such as the type of tea, the brew time, the amount of tea, and the serving temperature. I think that ideally, I’d randomize all those dimensions, gather a large sample, and then fit some kind of regression.

Creating dozens of different brews and then serving them all blinded at different serving temperatures sounds like way too much work. Maybe there’s an easier way to go about this? Can someone build me a robot?

If you thirst to see Subject C’s raw aroma scores or whatever, you can download the data or click on one of the entries in this table:

Subject Aroma Flavor Strength Goodness Quality

A x x x x x

B x x x x x

C x x x x x

D x x x x x

All x x x x xSubject D was really good at this; why can’t everyone be like Subject D?

I have (as will become clear..) Many Opinions about tea, and I am very doubtful of these results!

1) Considerably stronger results (..and possibly also stronger tea..) should be needed to overturn a lifetime's experience in making and drinking tea, not to mention the existing literature:

Douglas Adams' "How to make tea, for Americans": https://hatterstea.wordpress.com/2011/04/21/douglas-adams-on-tea/

George Orwell's "A nice cup of tea": http://www.booksatoz.com/witsend/tea/orwell.htm

(I can wholeheartedly recommend both essays as being essentially right-headed about tea-making..)

2) The tea mugs weren't warmed with boiling water beforehand - as every English grandmother will tell you, one must warm the pot before making tea in it. This effect probably scales with temperature, so the boiling water was probably cooled by the mugs more than the 80°C water was.

2.5) (Speaking of English grandmothers, they will also tell you that one brings the pot to the kettle, never the kettle to the pot: the English grandmother vote is definitely on the side of actually-boiling water, here...)

3) Even a small quantity of sugar obscures the taste of tea, even very strong tea, so overwhelmingly that the "with sugar" results for all categories (except possibly "aroma" - unsure about this one!) are likely tracking micro-variations in the sweetness of the tea rather than the actual flavour of the tea.

3.5) (Also, as any Indian grandmother will tell you: when one adds sugar, even a single granule, one simply ruins a pot of tea!)

3.75) (For this reason, scoring sugar-flavoured tea more highly than tea-flavoured tea ought to have been a sufficient exclusion criterion for any participant...)

4) I would guess that all the participants were American - if so, I think this introduces a considerable bias. Specifically, I think the American palate genuinely is different enough from the palates of tea-drinking cultures that appreciating tea brewed the right way is probably a learned skill for most Americans, compared to nations wherein (in generations past, at least: not so much now) youths grew up drinking tea. (This works both ways round, I'm sure: to the British palate, pretty much all American stuff, from beer to chocolate, just frankly tastes ruddy peculiar!)

5) "Export" tea is often bagged differently: much thicker bags are used so that there's no chance of the bag splitting and no chance of even a single tea leaf escaping through a hole (both of these things are harmless - rather, as indicators of a sufficiently-permeable teabag, they can be a good sign - but for some reason export markets seem to be concerned with them over and above lesser teabag considerations such as permeability..)

(These 'export' bags are sometimes identifiable by being individually enclosed in sachets, or having a string and a cardboard tab attached, or having a slightly plastic-ey texture - none of which, by the way, contribute anything of value either to the flavour of the tea or to the tea-making process.) I suspect that these bags limit the infusion rate enough to confound the experiment: even brewing tea with "normal" teabags makes it come out weaker than loose-leaf tea - and if I make tea with the "export" teabags I have found that I usually have to put two in to get a reasonable strength tea - and I don't even drink my tea particularly strong!

6) The statistical methodology was flawed: obviously it ought to have been *puts on sunglasses* a t-test.

Unfortunately this is a high-dimensional domain. Brewing extracts different chemicals at different rates (modulo temperature and agitation), but also changes or volatilizes some of them in the process. Caffiene and aromatics come out early. Tannins come out later (which make over-extracted black tea taste like ass). Oolong and green teas can develop a nice pot liquor (i.e. the tea feels velvety or viscous) with more extraction, but in doing so you volatilize (and lose) some of the aroma. All of that interacts with everyone's individual preferences.

This seems to be why people who get into tea like to do several short brews of the same leaves (with small amounts of water). It's sort of a pointless exercise with fully-oxidized black tea, but takes you on a flavor journey with, (e.g.) a loose leaf oolong that was picked within the past year. At the end it can feel like a sweet and savory soup broth.