Good if make prior after data instead of before

because truth is many

They say you’re supposed to choose your prior in advance. That’s why it’s called a “prior”. First, you’re supposed to say say how plausible different things are, and then you update your beliefs based on what you see in the world.

For example, currently you are—I assume—trying to decide if you should stop reading this post and do something else with your life. If you’ve read this blog before, then lurking somewhere in your mind is some prior for how often my posts are good. For the sake of argument, let’s say you think 25% of my posts are funny and insightful and 75% are boring and worthless.

OK. But now here you are reading these words. If they seem bad/good, then that raises the odds that this particular post is worthless/non-worthless. For the sake of argument again, say you find these words mildly promising, meaning that a good post is 1.5× more likely than a worthless post to contain words with this level of quality.

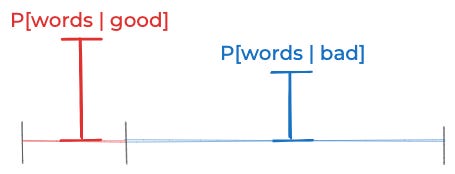

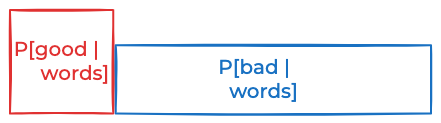

If you combine those two assumptions, that implies that the probability that this particular post is good is 33.3%. That’s true because the red rectangle below has half the area of the blue one, and thus the probability that this post is good should be half the probability that it’s bad (33.3% vs. 66.6%)

(Why half the area? Because the red rectangle is ⅓ as wide and ³⁄₂ as tall as the blue one and ⅓ × ³⁄₂ = ½.)

Theoretically, when you chose your prior that 25% of dynomight posts are good, that was supposed to reflect all the information you encountered in life before reading this post. Changing that number based on information contained in this post wouldn’t make any sense, because that information is supposed to be reflected in the second step when you choose your likelihood p[good | words]. Changing your prior based on this post would amount to “double-counting”.

In theory, that’s right. It’s also right in practice for the above example, and for the similar cute little examples you find in textbooks.

But for real problems, I’ve come to believe that refusing to change your prior after you see the data often leads to tragedy. The reason is that in real problems, things are rarely just “good” or “bad”, “true” or “false”. Instead, truth comes in an infinite number of varieties. And you often can’t predict which of these varieties matter until after you’ve seen the data.

Aliens

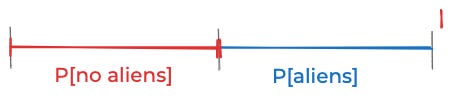

Let me show you what I mean. Say you’re wondering if there are aliens on Earth. As far as we know, there’s no reason aliens shouldn’t have emerged out of the random swirling of molecules on some other planet, developed a technological civilization, built spaceships, and shown up here. So it seems reasonable to choose a prior it’s equally plausible that there are aliens or that there are not, i.e. that

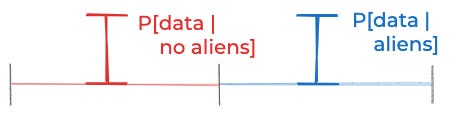

P[aliens] ≈ P[no aliens] ≈ 50%.Meanwhile, here on our actual world, we have lots of weird alien-esque evidence, like the Gimbal video, the Go Fast video, the FLIR1 video, the Wow! signal, government reports on unidentified aerial phenomena, and lots of pilots that report seeing “tic-tacs” fly around in physically impossible ways. Call all that stuff data. If aliens weren’t here, then it seems hard to explain all that stuff. So it seems like P[data | no aliens] should be some low number.

On the other hand, if aliens were here, then why don’t we ever get a good image? Why are there endless confusing reports and rumors and grainy videos, but never a single clear close-up high-resolution video, and never any alien debris found by some random person on the ground? That also seems hard to explain if aliens were here. So I think P[data | aliens] should also be some low number. For the sake of simplicity, let’s call it a wash and assume that

P[data | no aliens] ≈ P[data | aliens].Since neither the prior nor the data see any difference between aliens and no-aliens, the posterior probability is

P[no aliens | data] ≈ P[aliens | data] ≈ 50%.See the problem?

We’re friends. We respect each other. So let’s not argue about if my starting assumptions are good. They’re my assumptions. I like them. And yet the final conclusion seems insane to me. What went wrong?

Assuming I didn’t screw up the math (I didn’t), the obvious explanation is that I’m experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of a poor decision on my part to adopt a set of mutually contradictory beliefs. Say you claim that Alice is taller than Bob and Bob is taller than Carlos, but you deny that Alice is taller than Carlos. If so, that would mean that you’re confused, not that you’ve discovered some interesting paradox.

Perhaps if I believe that P[aliens] ≈ P[no aliens] and that P[data | aliens] ≈ P[data | no aliens], then I must accept that P[aliens | data] ≈ P[no aliens | data]. Maybe rejecting that conclusion just means I have some personal issues I need to work on.

I deny that explanation. I deny it! Or, at least, I deny that’s it’s most helpful way to think about this situation. To see why, let’s build a second model.

More aliens

Here’s a trivial observation that turns out to be important: “There are aliens” isn’t a single thing. There could be furry aliens, slimy aliens, aliens that like synthwave music, etc. When I stated my prior, I could have given different probabilities to each of those cases. But if I had, it wouldn’t have changed anything, because there’s no reason to think that furry vs. slimy aliens would have any difference in their eagerness to travel to ape-planets and fly around in physically impossible tic-tacs.

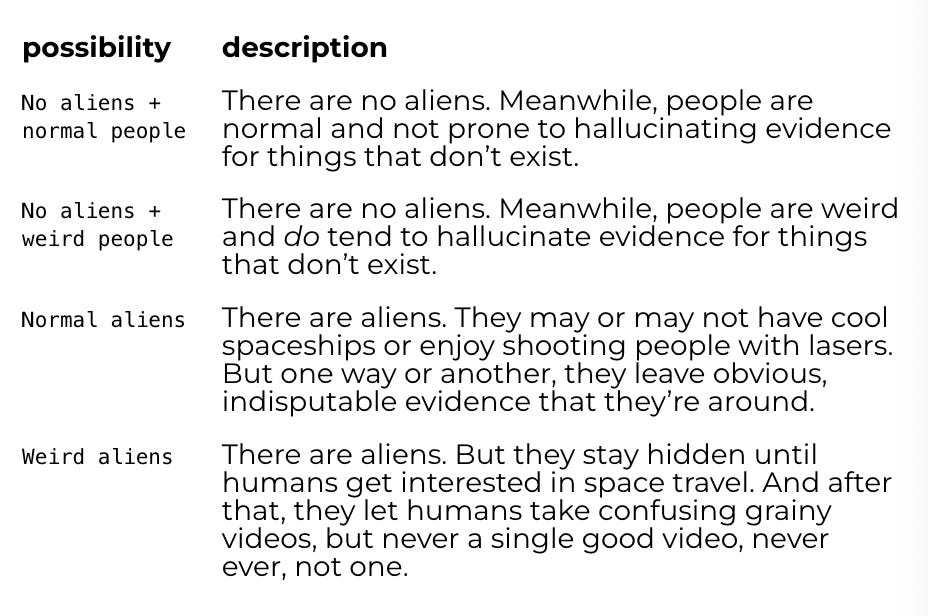

But suppose I had divided up the state of the world into these four possibilities:

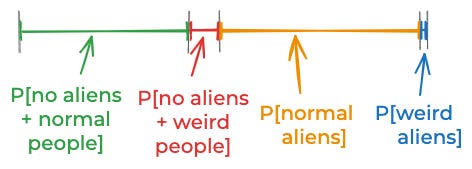

If I had broken things down that way, I might have chosen this prior:

P[no aliens + normal people] ≈ 41%

P[no aliens + weird people] ≈ 9%

P[normal aliens] ≈ 49%

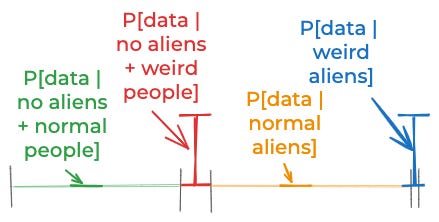

P[weird aliens] ≈ 1%Now, let’s think about the empirical evidence again. It’s incompatible with no aliens + normal people, since if there were no aliens, then normal people wouldn’t hallucinate flying tic-tacs. The evidence is also incompatible with normal aliens since is those kinds of aliens were around they would make their existence obvious. However, the evidence fits pretty well with weird aliens and also with no aliens + weird people.

So, a reasonable model would be

P[data | normal aliens] ≈ 0

P[data | no aliens + normal people] ≈ 0

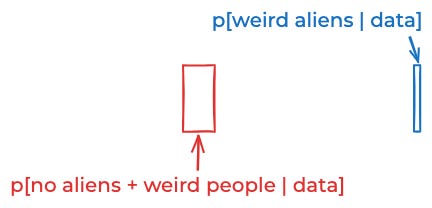

P[data | weird aliens] ≈ P[data | no aliens + weird people].If we combine those assumptions, now we only get a 10% posterior probability of aliens.

P[no aliens + normal people | data] ≈ 0

P[no aliens + weird people | data] ≈ 90%

P[normal aliens | data] ≈ 0

P[weird aliens | data] ≈ 10%Now the results seem non-insane.

Huh?

I hope you are now confused. If not, let me lay out what’s strange: The priors for the two above models both say that there’s a 50% chance of aliens. The first prior wasn’t wrong, it was just less detailed than the second one.

That’s weird, because the second prior seemed to lead to completely different predictions. If a prior is non-wrong and the math is non-wrong, shouldn’t your answers be non-wrong? What the hell?

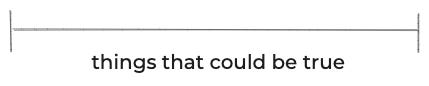

The simple explanation is that I’ve been lying to you a little bit. Take any situation where you’re trying to determine the truth of anything. Then there’s some space of things that could be true.

In some cases, this space is finite. If you’ve got a single tritium atom and you wait a year, either the atom decays or it doesn’t. But in most cases, there’s a large or infinite space of possibilities. Instead of you just being “sick” or “not sick”, you could be “high temperature but in good spirits” or “seems fine except won’t stop eating onions”.

(Usually the space of things that could be true isn’t easy to map to a small 1-D interval. I’m drawing like that for the sake of visualization, but really you should think of it as some high-dimensional space, or even an infinite dimensional space.)

In the case of aliens, the space of things that could be true might include, “There are lots of slimy aliens and a small number of furry aliens and the slimy aliens are really shy and the furry aliens are afraid of squirrels.” So, in principle, what you should do is divide up the space of things that might be true into tons of extremely detailed things and give a probability to each.

Often, the space of things that could be true is infinite. So theoretically, if you really want to do things by the book, what you should really do is specify how plausible each of those (infinite) possibilities is.

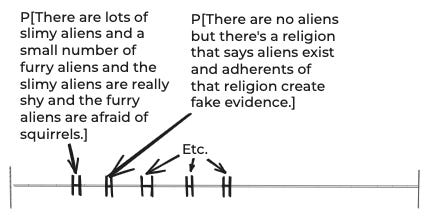

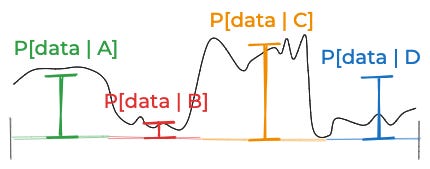

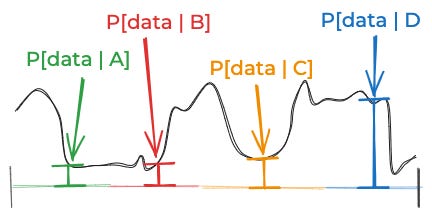

After you’ve done that, you can look at the data. For each thing that could be true, you need to think about the probability of the data. Since there’s an infinite number of things that could be true, that’s an infinite number of probabilities you need to specify. You could picture it as some curve like this:

(That’s a generic curve, not one for aliens.)

To me, this is the most underrated problem with applying Bayesian reasoning to complex real-world situations: In practice, there are an infinite number of things that can be true. It’s a lot of work to specify prior probabilities for an infinite number of things. And it’s also a lot of work to specify the likelihood of your data given an infinite number of things.

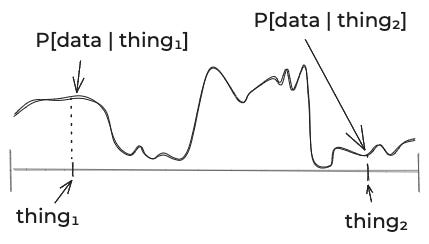

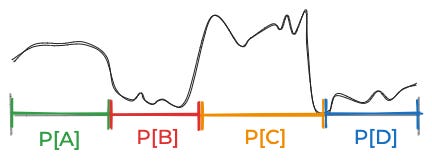

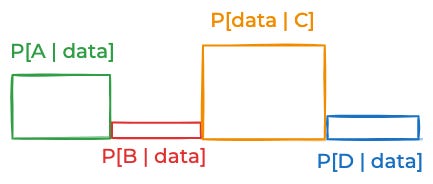

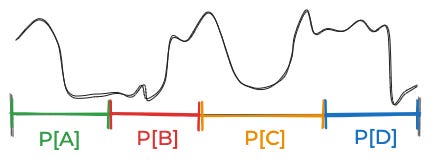

So what do we do in practice? We simplify, usually by limiting creating grouping the space of things that could be true into some small number of discrete categories. For the above curve, you might break things down into these four equally-plausible possibilities.

Then you might estimate these data probabilities for each of those possibilities.

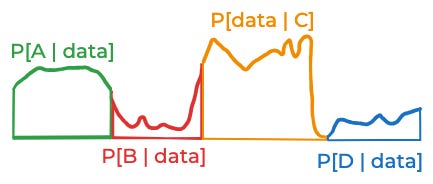

Then you could put those together to get this posterior:

That’s not bad. But it is just an approximation. Your “real” posterior probabilities correspond to these areas:

That approximation was pretty good. But the reason it was good is that we started out with a good discretization of the space of things that might be true: One where the likelihood of the data didn’t vary too much for the different possibilities inside of A, B, C, and D. Imagine the likelihood of the data—if you were able to think about all the infinite possibilities one by one—looked like this:

This is dangerous. The problem is that you can’t actually think about all those infinite possibilities. When you think about four four discrete possibilities, you might estimate some likelihood that looks like this:

If you did that, that would lead to you underestimating the probability of A, B, and C, and overestimating the probability of D.

This is where my first model of aliens went wrong. My prior P[aliens] was not wrong. (Not to me.) The mistake was in assigning the same value to P[data | aliens] and P[data | no aliens]. Sure, I think the probability of all our alien-esque data is equally likely given aliens and given no-aliens. But that’s only true for certain kinds of aliens, and certain kinds of no-aliens. And my prior for those kinds of aliens is much lower than for those kinds of non-aliens.

Technically, the fix to the first model is simple: Make P[data | aliens] lower. But the reason it’s lower is that I have additional prior information that I forgot to include in my original prior. If I just assert that P[data | aliens] is much lower than P[data | no aliens] then the whole formal Bayesian thing isn’t actually doing very much—I might as well just state that I think P[aliens | data] is low. If I want to formally justify why P[data | aliens] should be lower, that requires a messy recursive procedure where I sort of add that missing prior information and then integrate it out when computing the data likelihood.

I don’t think that technical fix is very good. While it’s technically correct (har-har) it’s very unintuitive. The better solution is what I did in the second model: To create a finer categorization of the space of things that might be true, such that the probability of the data is constant-ish for each term.

The thing is: Such a categorization depends on the data. Without seeing the actual data in our world, I would never have predicted that we would have so many pilots that report seeing tic-tacs. So I would never have predicted that I should have categories that are based on how much people might hallucinate evidence or how much aliens like to mess with us. So the only practical way to get good results is to first look at the data to figure out what categories are important, and then to ask yourself how likely you would have said those categories were, if you hadn’t yet seen any of the evidence.

One simple solution is to divide the data into two groups: one for figuring out which categorization makes the most sense, and the other for calculating the posterior.

I guess it is with Bayesianism as it is with Utilitarianism: technically correct as a description, but completely (and will forever be) useless in practice.