Do you need permission from the government to do independent research?

IRB you kidding me?

(This post has been updated. Read the latest version at dynomight.net/irb)

Some of my favorite internet people sometimes organize little community experiments. Like, let’s eat potatoes and see if we lose weight. Or, let’s try take some supplements and see if anxiety goes down. I’ve toyed with doing one myself, to see if theanine (a chemical in tea) really helps with stress.

But sometimes, when everyone is having fun, some very mean very bad people show up and say, “HEY! YOU CAN’T DO THAT! THAT’S HUMAN SUBJECTS RESEARCH! YOU NEED TO GET APPROVAL FROM AN INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD!”

So I wondered—is that right? Who exactly actually needs to get approval from an institutional review board (IRB)? More than a year later, I’m now convinced that:

No single source on the internet actually answers that question.

The answer is absurdly complex.

The reason it’s so complex is that IRB rules are an illegible mishmash of things, some of which themselves have near-fractal complexity.

If you stare at this long enough, it’s impossible not to question the degree to which we actually have “laws”.

In this post, I’ll give the answer and then explain—in maddening detail—why I think that answer is right. But first I want to tell a little story.

I used to live in an apartment with an extremely steep driveway. When I had visitors, I’d tell them, “At the bottom of the driveway you must slow to ⅒ of normal speed or your car will scrape the ground. I tell this to everyone and they only slow to ½ of normal speed and scrape their car on the ground. Don’t do that!” Then they’d only slow to ½ of normal speed and scrape their car on the ground.

Why? I think because my visitors simply couldn’t believe my driveway was as stupid as it was. When I explained the rules of safe driveway usage, they mentally substituted the closest version of those rules that would be correct in a sane universe, one without driveways that form sudden 30° angles with the road. I suspect this is a general cognitive bias.

So, who exactly needs IRB approval? Here are some myths:

Myth: IRB approval is only needed for medical research.

Myth: IRB approval is only needed for federally funded research.

Myth: IRB approval is only needed for research at “institutions”.

Myth: IRB approval is only needed if you want to publish in a journal.

Wrong. But this is also a myth:

Myth: IRB approval is needed for all research involving human subjects.

Also wrong. As far as I can tell, after months of research, here is how it works:

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “That can’t be right! The government can’t possibly claim to regulate what me and my roommates eat at home! That would be stupid!” Yes, it would be stupid. But who says the world makes sense?

Now, would you actually be prosecuted for violating those rules? Unlikely. If a prosecutor went after you and you fought them in court, you might even be able to get some of these rules declared unconstitutional. But those are the rules as written.

Caution: I estimate a 85% chance that this post contains at least one minor error and a 40% chance of a significant error. I’ve gone to insane lengths to try to get things right—I regret ever becoming interested in this topic—but this stuff is insanely convoluted. Past experience says that someone reading this knows much better than I do. If that’s you, let me know about any errors.

Reminder of how law works in the US

If you’re a sane person, and you want to know when IRB approval is needed, you might think something like, “I know! I’ll go find the IRB law and read it. Then I’ll know what’s legal and what isn’t. Yay!”

Hahaha, no. This won’t work, for several reasons.

For one, few federal rules actually come from laws. Usually politicians pass some broad law that says, “Human research is hereby regulated, details to come!” And then government employees write regulations that contain all the details, and those regulations have the power of law. And then the government employees issue “clarifications” that supposedly don’t change anything, but everyone treats like new laws.

Also, the US constitution theoretically imposes severe limits on the power of the federal government. Article 1 section 8 says the federal government has the power to (1) tax and spend, (2) regulate commerce, (3) control citizenship, (4) create post offices, (5) protect IP, (6) make treaties and (7) do war. And the 10th amendment says that’s it: everything else is left to the states.

The federal government doesn’t like those limits, so it evades them in various ways. The classic trick is to declare that everything is related to commerce and therefore almost anything can be considered “regulating commerce”. For example, it’s OK to make growing and eating wheat on your own property illegal, because growing and eating wheat is “commerce”. Another trick is to write rules that sort of say, “If your state/organization wants back any of the money it’s paying in taxes, then you must create and enforce the following rules: […]”. For example, in 1984, the US government decreed that all states must raise the legal age to buy alcohol to 21 or they would lose federal funding for highways.

Finally, the limits of federal power are only clarified when someone fights them in court. Did you know that at some point, bureaucrats decided that your boss must guess your race and report it to the government? Is that an illegal overreach? Is it “regulating commerce” to make personal consumption of cannabis illegal in states that have legalized it? The way you find out is you break the rules, get prosecuted, and spend millions fighting in court. (For cannabis, the answer is yes, that is regulating commerce.) If you win, OK, no refunds on your legal fees. If you lose, you pay massive fines or go to prison. Also, courts have constantly changing judges and opinions.

So what happens in practice is politicians write a vague law. Bureaucrats turn that law into very detailed (but often still vague) specific rules. Those rules might or might not be “legal”, but nobody want to risk fighting them in court. If the regulations are particularly ridiculous or likely to be overturned if challenged, prosecutors may quietly stop bringing cases. But the regulations still sit there on the books. And people still usually pay attention to them, because why risk it?

OK! Where do IRB regulations come from?

The Common Rule

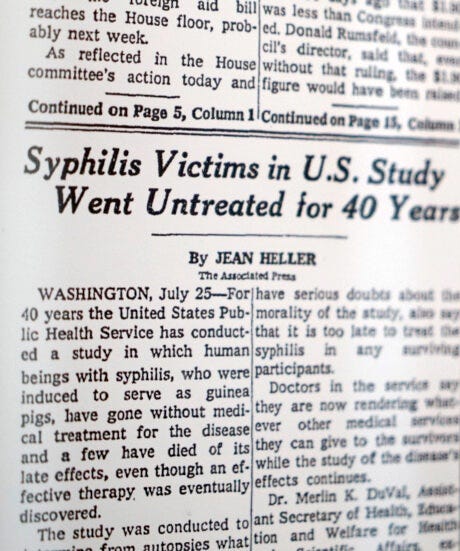

In 1932, the United States government and Tuskegee University began studying 600 poor black sharecroppers in Macon Country Alabama, ⅔ of whom had latent syphilis. The idea was to observe the progression of the disease if left untreated. By the late 1940s, syphilis was easily treatable with penicillin, but the men were never informed of their condition, never treated, and were even given fake treatments and diagnoses.

In 1965, Peter Buxton joined the Public Health service and soon learned of the experiment. He was horrified and filed several official protests, but all were all rejected. Finally, in 1972, Buxton leaked the details to Jean Heller of the Associated Press which led to this front-page article on July 26, 1972.

The led to widespread outrage and cancellation of the study. By this time, dozens of the men had died from syphilis and many of their wives and children had also become infected.

It also led, in early 1973, a series of congressional hearings led by Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. These hearings eventually produced the National Research Act. Several people voted for the first version of this bill and then against the second version, including one Joseph Biden of Delaware, though I can’t find any record of why. Anyway, it was signed into law by Richard Nixon on July 12, 1974.

Formally speaking, the National Research Act did was to create a commission to develop guidelines for ethical research in human subjects, including how IRBs should work. But in reality, it also sent a message that federal agencies should use their existing authority to regulate research. Even before the Act was passed, the Department of Health and Human Services had started amending the federal code to regulate human research. In 1978, the commission issued a report on IRBs:

The Commission believes that the rights of subjects should be protected by local review committees operating pursuant to federal regulations and located in institutions where research involving human subjects is conducted.

[…]

The Commission further believes that institutions receiving federal support for the conduct of research involving human subjects should be governed by uniform federal regulations applicable to the review of all such research, whether it is supported by one federal department or another, or is not federally supported.

Informed by this report, lots of different agencies issued different regulations. This continued until 1991, when 15 federal agencies harmonized on what is known as the Common Rule, because it is “common” to different federal agencies. This is now codified as Title 45 Part 46 of the federal code.

Since 1991, this has been continuously updated and various other agencies have joined, notably the department of Labor. There are still a couple holdouts including the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the National Endowment for the Humanities. The CIA is an odd case—they never issued any formal regulations, but supposedly apply the Common Rule because of a cryptic executive order from 1981. The FDA hasn’t joined because they have their own regulatory structure.

So what does the Common Rule say? In principle, you can go here and read it. Good luck with that. It’s exactly as readable as “a series of regulations amended by many agencies over many decades” sounds like it would be. But basically (1) It requires informed consent. (2) It requires that risks are reasonable in relation to expected benefits, not including any long-range benefits from new knowledge. (3) It requires participants are selected fairly and equitably (e.g. not all poor black sharecroppers) Finally, (4) It requires that federally funded research with human subjects is reviewed by an IRB.

Now, that might sound simple, but what exactly is “research”? This is defined by 45 CFR 46.102(l) to be a “systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.” It’s best to understand this with an example. Say you’re a teacher and you want to test if the cognitive bias of anchoring applies to your class. Is this research? If you’re doing it as part of normal “teaching stuff”, to demonstrate the effect to your students, then no. But if you’re doing it in hope of learning if the anchoring bias is real, then that is research. To some degree, the truth lies in your heart.

(The definition of a “human subject” is also somewhat convoluted: What if you’re using data someone else gathered? What if you’re just using some human tissue samples or nonviable human embryos? But never mind.)

Note that this applies to all research. The people who made these rules were almost all medical researchers thinking about serious medical risks. But they wrote the rules to apply to all research, including research where you might just ask people some questions.

There are some narrow categories of research that are “exempt” from IRB review, e.g. research on standard educational methods or food taste evaluations, or certain benign behavioral interventions . Theoretically, an institution could allow investigators to decide for themselves if they are exempt, but this is not recommended, and in practice, essentially all institutions require you to apply for a determination of exemption. In reality, no research is really exempt, it’s just that certain categories of research have a somewhat more lightweight application process. To get a feel for how much friction this adds, here’s U. Michigan’s application for exemption.

Up until the 1990s, IRBs at universities tended to be staffed with faculty “volunteers”. These were sympathetic to the needs of their colleagues, had little interest in reading (unreadable) federal regulations, and probably just wanted to get back to teaching and research. So IRBs were often pretty loose. But in 1996, Hoiyan Wan died after taking part of an experiment on the effects of smoking and air pollution the University of Rochester. And in 1999, Jesse Gelsinger died after taking an experimental gene therapy at the University Of Pennsylvania. Federal agencies cracked down and sent out hundreds of enforcement letters. Universities nervously responded with “hypercompliance”, leading to IRB process everyone loves today.

Why is the Common Rule so common?

The 1978 commission recommended that any institution accepting federal funding must apply IRB rules to all research, regardless of funding source. But the written regulations did not follow that recommendation. Theoretically, a university could accept federal funding for some research and still allow other research on human subjects without any IRB approval. But in practice, no university ever does that. Why?

Well, before giving any federal funding to an institution, the government requires the institution to file a “Federalwise Assurance”. In this, the institution must promise to obey some “statement of ethical principles”. Supposedly this could be anything, but it appears that the only correct answer is “The Belmont Report”, an ethics statement issued by the same commission from 1978. Then there is a section where the institution may “optionally” promise to apply the common rule to all research, regardless of funding source.

The government has a database of these “assurances”, but you can’t actually read them. Still, I found that a few prominent institutions that had published theirs. They all promised to abide by the Belmont report. Some (NYU, U. C. Irvine) promised to apply the Common Rule to all research, but most (Mayo Clinic, U. Florida, Emory, U. Michigan, MIT) do not.

So if you’re a researcher at MIT, can you do non-federally funded research without an IRB? Nope. MIT rules still say you need an IRB for all research with human subjects. So do the Mayo Clinic’s. So do U. Florida’s rules. So do Emory’s rules. So do U. Michigan’s rules.

What’s going on here? Throughout the 1970s, there was a debate about if IRB rules should apply to social science at all. The OHRP (which oversees the Common Rule) gradually asserted more and more broad IRB requirements. Ithiel de Sola Pool, a professor at MIT, protested this growing power. Apparently, a colleague had sought IRB approval to interview Boston anti-busing activists, and been rejected because this research could be used against them. Pool argued that much of social science should be exempt and got support from professional societies.

But no matter. Here’s Charles McCarthy, director of the OHRP from 1977 to 1993, bragging about subverting the Carter and the Reagan administrations to add more regulations during the transition in 1980:

But we were trying to decide when is the appropriate time to get the Secretary to sign off on the new regulations? They had already been proposed, we had got comments from the public. We’d incorporated the comments. We wrote the preamble, it was ready to go. And then when is the best time, ‘cause Harris could care less whether they every got published. So we talked to the transition team, and they said Reagan will never allow new regulations to see the light of day, so if you’re going to get those out at all, you’d better get them out before he takes over.

So we’re struggling with this problem, and the way we worked it out was that’s when we wrote, overnight one night–brilliant inspiration–we wrote–everybody stayed in the office, and we worked all night long, and we wrote the exemptions to the regulations, and we also wrote expedited review neither of which had ever been addressed by the Commission. And that’s where they came from.

Then we went to the transition team, and we said would the transition team endorse regulations that are less stringent than the previous regulations? And, of course, they weren’t, but they looked like they were because we wrote some exceptions. And so when we sent the package down to Harris, we said “Diminished Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects.” And that was the title. And, of course, we knew nobody down there in the last weeks of the Harris administration getting ready to leave office would actually read it. So they didn’t know what all that was about, but they could read the title.

And so Secretary Harris signed that at her farewell party. She put down her glass of champagne and signed the regulations on January 19, 1980, and went out of office on the 20th. So we squeaked by. Those were some of the adventures we had that were kind of harrowing for regulators, and that’s why some of the language in those exemptions is so convoluted because it was really a first draft. But it survived and it’s still in there. And it makes some sense, but if we could rewrite the regulations, we would run that through three or four more drafts and make them crystal clear. They’re less than elegant writing, whereas if you read the rest of the regulation, I think you’ll find sub-part A is very well-written if you leave out the part about the exemptions.

That’s a real quote that you can go read on the hhs.gov website today.

The OHRP sent out “non-binding guidance” that suggested all research should be subject to IRB review. According to Hamburger (2007) in the 1990s, the Federalwise Assurance form implied that institutions had to apply the Common Rule to all research, despite the fact that no federal regulation to this effect existed. I can’t find the old form, but according to “persons who were in a position to know”, at one point all but about five institutions in the entire country had made this promise.

By 2000-2005, the form made clear that promising to apply the Common Rule (and thus IRBs) to non federally-funded research was optional, and many institutions decline to do this. But they are only declining to make this assurance. Apparently, after years of applying the Common Rule to all research, it had risen to legally qualify as the “standard of care”, meaning that anyone that failed to apply it risked being legally “negligent “ under state law. So, having established the Common Rule as standard through questionably legal tactics, the government could now relax and rely on state tort laws.

Now, say you’re affiliated with a university. Federal funded research without IRB approval is out. Any research at the university is out. But say you want to do research in your spare time, at home, without using any university resources. Is that OK?

Policies here seem to vary. Some are clear that this is not OK. U.C. San Francisco says:

UCSF faculty, staff, or students or researchers at UCSF-affiliated institutions conducting human subjects research require IRB approval before initiating the study. IRB approval is required regardless of the site of the study or the source of funding (if there is funding).

Others are a bit ambiguous. MIT says:

Any faculty member, employee or student at MIT who conducts human subjects research must apply [to the IRB] if the research involves any form of MIT involvement or support, including funding, personnel, facilities, academic credit or access to experimental subjects.

But how could a MIT employee do research without involving MIT personnel, when they themselves are personnel? The closest I can find to anyone saying it’s OK to do independent research without an IRB is Columbia University which says an IRB is needed if:

the research is conducted by or under the direction of any employee or agent (faculty/student/staff) of Columbia, in connection with his or her institutional responsibilities

What exactly constitutes a “connection”? I guess you get to argue about the meaning of that term if/when you’re investigated for research misconduct.

Journals

OK! So if you’re doing any research at any federally funded institution, you need an IRB. If you work at such an institution, you could maybe do research at home, as long as it’s unrelated to your job and you’re willing to live dangerously.

But suppose you’re not affiliated with any institution. Can you do research without an IRB?

One additional barrier is that if you want to publish your results in a journal, almost all journals that publish human subjects research require IRB approval. For example, all Nature journals, Springer journals , and Taylor and Francis journals require you to identify the ethics committee and give a reference number. Science journals require IRB approval, but don’t seem to require details unless an editor requests them. (Those are publisher requirements. Specific journals can add additional restrictions.)

Now, I’m not sure how carefully these journals actually check. My impression is that some do and some don’t. Maybe you could lie and get away with it, but papers do in fact retracted when a lack of IRB approval is revealed.

State laws

Another barrier is that some states have their own laws. In 1975, New York passed a law that required IRB approval for all human subjects research:

Each person engaged in the conduct of human research or proposing to conduct human research shall affiliate himself with an institution or agency having a human research review committee, and such human research as he conducts or proposes to conduct shall be subject to review by such committee in the manner set forth in this section.

Virginia passed a very similar law in 1979. These go further than requiring IRB approval. They make independent human subjects research fully illegal! (Read that quote!) In most states, a random person could submit their research plan to an independent IRB. Not in New York or Virginia.

In 2002, Maryland passed house bill 917. I find this text extremely confusing, but everyone seems to agree that it means that all human subjects research requires IRB approval.

I’ve seen many people claim that California also requires IRB approval for all human subjects research. While it’s true that California has some extra regulations, as far as I can tell none of these require IRB approval.

FDA regulations

Have you found all this to be too simple? Too straightforward and legible?

The FDA is here to help. They have an independent set of IRB regulations. While the Common Rule IRB regulations are in Title 45 Part 46 (45 CFR 46), the FDA IRB regulations are in 21 CFR 56 and also 21 CFR Part 50.

Whereas the Common Rule derives its constitutional authority from the idea that the government can decide how it wants to give out money, the FDA regulations seem derive their constitutional authority from the idea that it is regulating commerce. So FDA regulations apply regardless of where you work or how you’ve gotten funding. The FDA operates according to the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act and its many amendments, most notably the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act.

So what do the FDA regulations say? I found them to be much more painful to read than the (already extremely painful) Common Rule regulations. But after much thrashing and screaming, I think the core regulation is 21 CFR 56.103(a):

[…] any clinical investigation which must meet the requirements for prior submission (as required in parts 312, 812, and 813) […] shall not be initiated unless that investigation has been reviewed […] by an IRB meeting the requirements of this part.

So what does this mean?

Well, a “clinical investigation” is defined by 21 CFR 56.102(c) to be anything involving human subjects and a “test article”. And a “test article” which is defined in turn by 21 CFR 56.102(l) to be any “drug” for human use. So if you’re doing anything with a “drug” that requires “prior submission”, then you need an IRB. What do those terms mean? 21 CFR Part 312 makes clear that “prior submission” is referring to an investigational new drug (IND) application to the FDA.

(Caution: An “IRB” and an “IND” are totally different things. An IRB is what this article is about. An IND is the kind of application that pharmaceutical companies make to the FDA before they can start clinical trials.)

So, at first, this seems like good news: As long as you don’t need to do a (gigantic, extremely expensive) IND application to the FDA before starting your research, then FDA regulations don’t force you to use an IRB. Whew! Except… When are you supposed to submit an IND? Surely that’s not some incredibly broad set of circumstances that could apply to almost anyone doing almost anything, is it?

This is a supposedly “nonbinding” document that that supposedly just explains old rules. Supposedly the FDA is just publishing this as a helpful service to all the mouth-breathers who can’t understand the federal regulations. But everyone in industry behaves as if it’s a new law. Which is understandable, since the written regulations are so confusing and ambiguous.

If you read this guidance, you will discover that an IND is needed if:

The research involves a “drug”

The research is a “clinical investigation”

The research is not exempt.

If you want to avoid an IND, then 2. and 3. are little help. The term “clinical investigation” in is defined as anything where a “drug” is given to human subjects. And the exemptions are extremely narrow: They are only for marketed drugs where the drug is being used for the labeled purpose as directed. Testing something already approved for a disease? Not exempt. Testing if normal food helps with some new disease? Not exempt. You’re only exempt if you’re doing research on something the FDA has already accepted to be true.

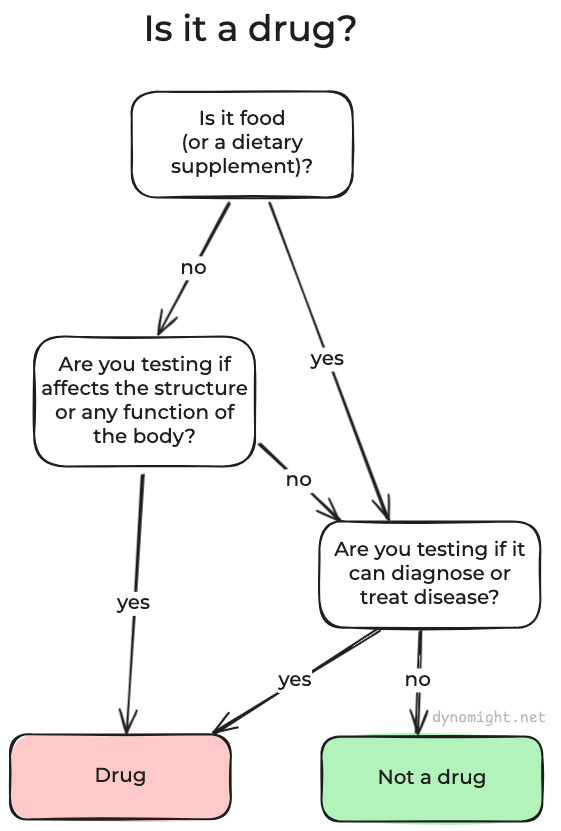

If you want to avoid an IND, your best hope is that your research doesn’t involve a “drug”. Unfortunately, the term “drug” is defined extremely broadly, way beyond the colloquial meaning of “drug” in English. A drug is defined to include:

articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease

It also includes:

articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body

Get that? Here’s a little picture:

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “That can’t be right! That would mean that if I wanted to study if some normal food reduced the odds of, say, diabetes, then I wouldn’t just need IRB approval, I would also need to submit a freaking IND! That would be stupid!”

But the FDA is quite clear that this is right:

As is the case for a dietary supplement, a food is considered to be a drug if it is “intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease,” except that a food may bear an authorized health claim about reducing the risk of a disease without becoming a drug (see section VI.D.3). Therefore, a clinical investigation intended to evaluate the effect of a food on a disease would require an IND under part 312. For example, a clinical investigation intended to evaluate the effect of a food on the signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease would require an IND.

FDA also says:

Does a physician, in private practice, conducting research with an FDA regulated product, need to obtain IRB approval?

Yes. The FDA regulations require IRB review and approval of regulated clinical investigations, whether or not the study involves institutionalized subjects. FDA has included non-institutionalized subjects because it is inappropriate to apply a double standard for the protection of research subjects based on whether or not they are institutionalized.

An investigator should be able to obtain IRB review by submitting the research proposal to a community hospital, a university/medical school, an independent IRB, a local or state government health agency or other organizations.

At first, I thought this couldn’t possibly be true. In 2017, it apparently cost $619,200 to submit an IND application to the FDA. However, in practice it appears that there are many exceptions and that there are two categories of INDs: Commercial and research. I assume the FDA doesn’t actually try to charge researchers $619,200 to review their research projects, but I don’t really know.

The FDA’s IND application page is here. Have fun.

I’m not sure how seriously people take these FDA regulations in practice. People do seem to get IND approval for research on actual (chemical) drugs. But does anyone actually seek IND approval if they want to study if diet influences obesity? Do they carefully avoid talking about disease, so they can fall under the looser “structure and function of the body”? And is private research on normal food really a form of inter-state commerce? I’m just not sure.

What I’ve learned

Mostly I’ve learned that the set of abstractions I was using to think about the world were wrong. I assumed that there were “laws” that someone had written, and that someone could read to understand what is legal and what isn’t.

But in reality, politicians write vague laws, and then agencies write vague sprawling regulations, and then those agencies issue vague “clarifications”. Sometimes these might be unconstitutional or illegal, but no one knows unless they want to fight things in court. But courts are unpredictable, and even going to court is ruinously expensive. Trying to comply with the the written law is like trying to comply with a giant mound of potatoes.

So people basically operate as if the law doesn’t exist. The “law” is what the people who enforce the law choose to enforce. If you need to live in this world, that’s what you pay attention to. The law is what you can get away with.

What I would change

All the IRB rules were designed by medical doctors to regulate the research of other medical doctors, thinking about incidents like the Tuskegee syphilis study.

But here’s an opinion: Needing to submit an application before you can ask people to fill out some simple online survey is stupid. Needing to submit an application before you can interview a bunch of people is stupid.

I like incremental change, so why don’t we start by making “exempt” research actually exempt? For example, 45 CFR 46.104(d)(3)(ii) exempts “benign behavioral interventions” from IRB review. But you still need to apply to prove you’re exempt. Why?

As an analogy, driving a car is dangerous. Whenever I drive, I could easily kill someone. But the government doesn’t force me to submit a driving plan any time I want to go somewhere. Instead, if I misbehave, I am punished in retrospect. Why don’t we apply the same policy to research?

Notes

I found AI to be completely useless at parsing all these federal regulations. Maybe you need AI that’s specifically trained to be good at parsing legal text?

Say I want to feed potatoes to my friends and see if that reduces diabetes. Maybe that’s dumb. Fine. But the FDA seems to be claiming that it is constitutionally permitted to regulate this because by doing this I would be engaging in “interstate commerce”. Really?

Maybe the Chevron decision might have some implications for all this?

As far as I can tell, no one has ever been prosecuted anyone for failure to comply with IRB requirements. It’s not even clear what the penalty would be. In practice, rules are enforced on institutions—if one failed to comply, then their “assurance” might be cancelled, meaning they couldn’t take any federal funding for research. Or, if they wanted to sell something, the FDA might refuse to approve it for sale.

Are you chaotic good? Then you may find it interesting that it seems to be relatively easy to form a new IRB. (HHS rules / FDA rules). And that while all federally funded institutions require IRB approval for all research, only some require approval from their IRB. You can probably see where this is going.

Further reading

Philip Hamburger:

My Bookshelf Runneth Over:

Many thanks to Willy Chertman.

Wonderful article, thank you for doing this research. You point out that no one has been prosecuted for violations, which is encouraging, but in reality this is all enforced via social mechanisms. A personal example:

As a hobby, I help officiate ("judge") Magic: The Gathering tournaments. The game is complicated and the tournaments have high prizes, so the Magic judges have their own tests and certifications and whatnot to ensure they know what they're doing. There are always arguments over whether the tests are too hard or too easy, and what level of knowledge is reasonable to expect from the (extremely underpaid) judges.

I was curious myself to get an idea of the baseline, so I started keeping track of the rulings I saw other judges take and how many they got right or wrong. (Note: watching other judges answer questions about the game is normal and in fact encouraged in case they need help; the only thing I was doing differently was writing down the result on a notepad on my phone. This is happening in a large convention center, so I had no private access; any person off the street could have done the exact same thing.)

After I had observed a few hundred rulings from a few dozen different judges, I made a short post on my personal Facebook page, saying "of calls taken by level 1/2/3 judges that I watched, they got X% correct without needing my help".

Dozens of judges and players swarmed my post to tell me that I was doing human subjects research, and thus needed an IRB. I was told that I had violated the Nuremburg Code, and was "bringing Nazism into judging". Several said that, by not asking other judges for their explicit consent to write down their answer on a notepad, I had "violated their consent", and implied that this meant I was in support of rape. Of the ~6 companies that run large Magic tournaments in North America, every one of them proceeded to ban me from judging for them. Most still have me banned now, 3 years later.

So I don't think the core problem here is the government. The average person just really loves exerting control over others and preventing them from trying to learn things about others. Our dystopian regulatory system is just the will of the people in this respect.

See also psychiatrist Scott Alexander's blog post, "My IRB Nightmare", where he describes his surreal, Kafkaesque struggle to conduct a simple survey.

https://slatestarcodex.com/2017/08/29/my-irb-nightmare/