Integer programming easily encloses horse

Stop having fun without me

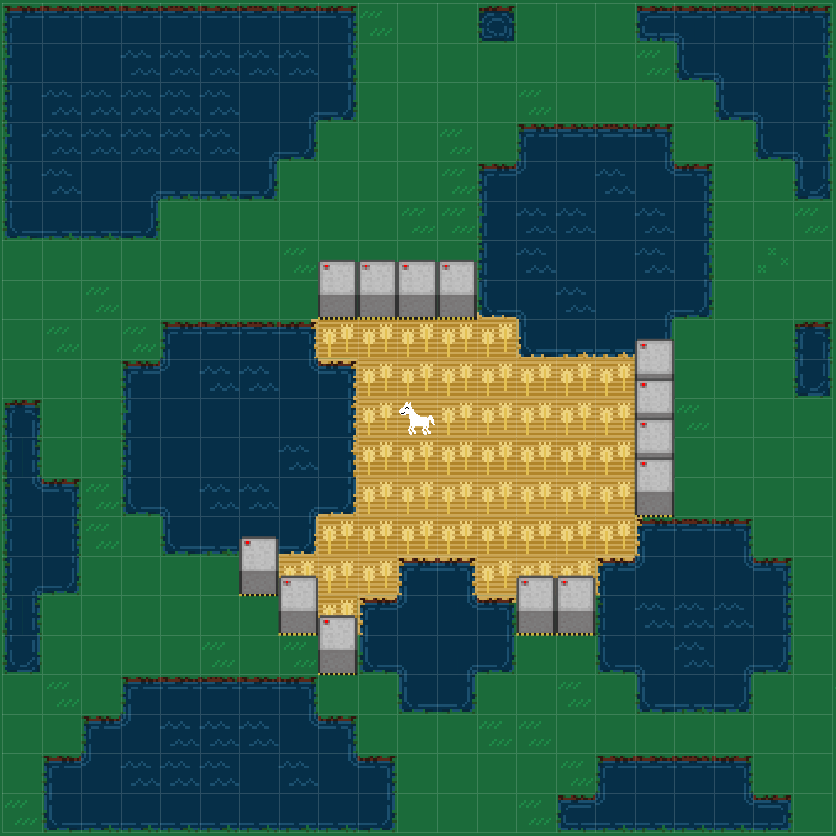

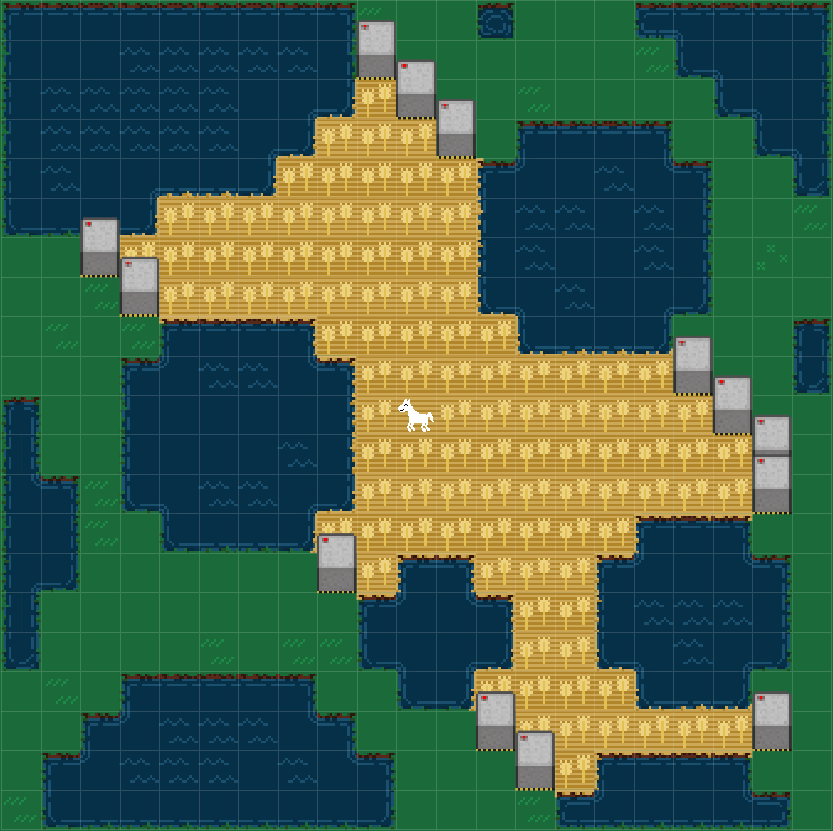

enclose.horse is a game in which you enclose a horse. You start with a map like this with water, fields, and horse.

Then you enclose horse. You have a finite budget of walls. (For the above map, 13.) You need to place them so that the horse is enclosed in as large an area as possible. The horse cannot move diagonally and cannot move over water.

Here’s one (bad) solution:

This is a charming little game. But something about it disturbs me. It’s exploring a mathematical structure (good) but it’s a disorganized mathematical structure that stubbornly resists understanding. There are—I think—no broad theorems or abstractions that might allow you to “derive” or “explain” the best solution for a given problem. If you want to know why the best solution is best, the honest answer is: Because it’s better than all of the other solutions.

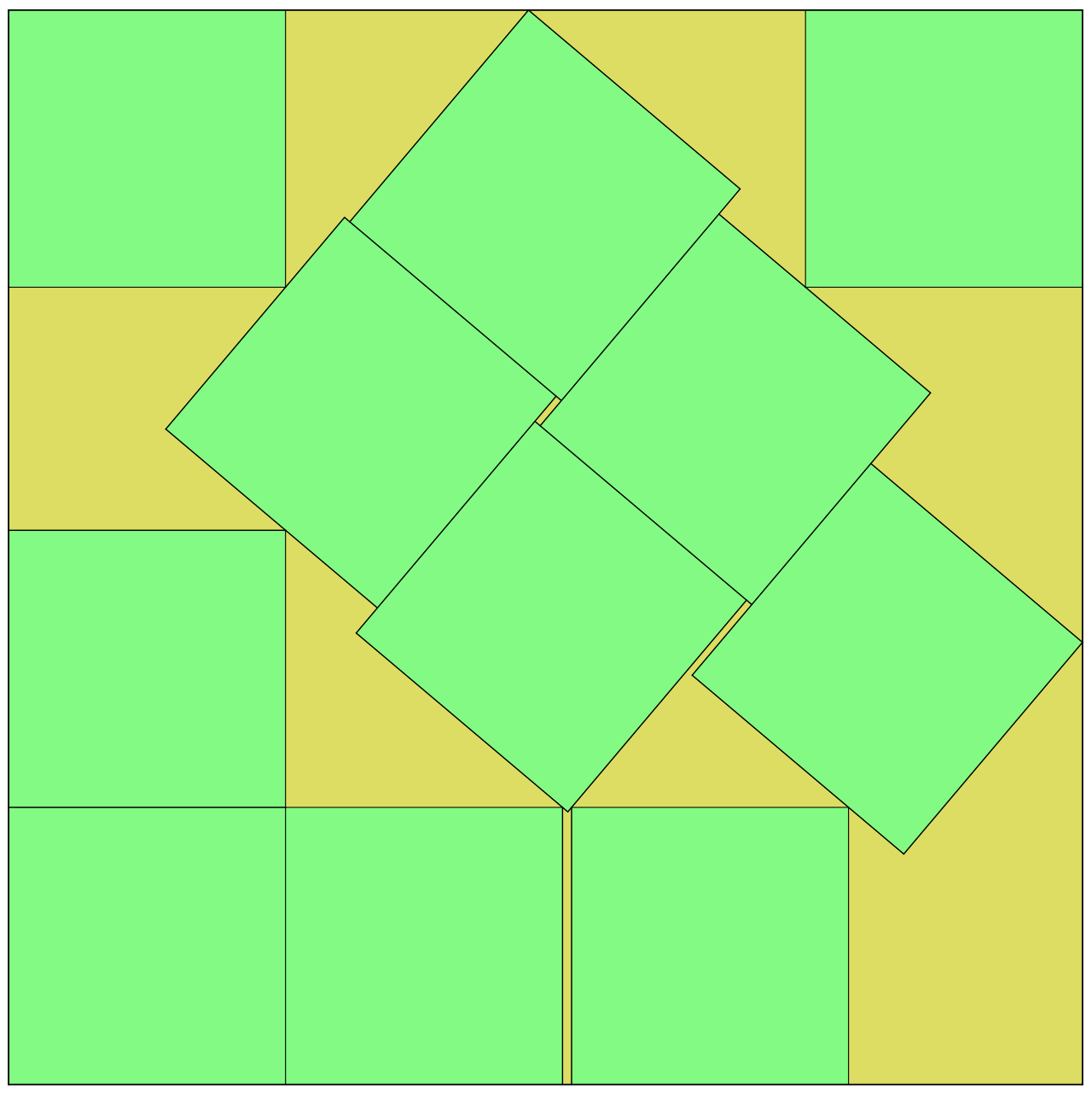

I guess that what really bothers me is living in such a disordered universe. Did you know that this is the most compact known way to pack 11 squares together into a larger square?

Really makes you think about the mindset of whoever made the universe, am I right?

Few people seem quite as bothered by this aspect of reality as I am. So, since I can’t enjoy this kind of game, I thought I’d try to ruin it for everyone by showing that it’s extremely easy for machines.

Integer programming

Integer programming is, I think, one of humanity’s most unsung achievements. If you’re not familiar with it, don’t be confused by the word “programming”. It’s not like C++ or whatever. It’s a type of mathematical optimization problem. You have some list of variables, and you want to minimize a linear function of those variables under linear (technically affine) constraints.

For example, you might want to minimize

3×a + 5×bwith respect to a and b under the constraints that

b ≥ 2,

3×a + b ≥ 10.If the variables are continuous, then this is just linear programming, which is theoretically pretty fast and in practice extremely fast.

However, if the variables are integers, then this is integer programming. Theoretically, this is NP-hard, meaning that it’s probably impossible to solve all integer programming problems in any reasonable amount of time.

But NP-hardness is not nearly as big a deal as people make it out to be. People have put a lot of effort into integer programming, because it’s useful for laying out chips, doing logistics and routing, managing supply chains, creating financial products and lots of other almost all real-world problems that involve constraints and discrete choices.

After decades of effort, we have solvers that are extremely good. For most real-world problems of moderate size, these solvers can not just find the optimal solution, but also provide a proof that that it’s actually optimal.

OK, enough ranting. Let’s enclose some horse.

Maps

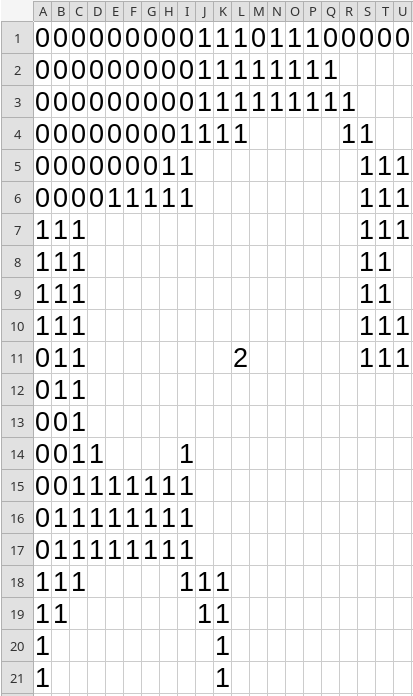

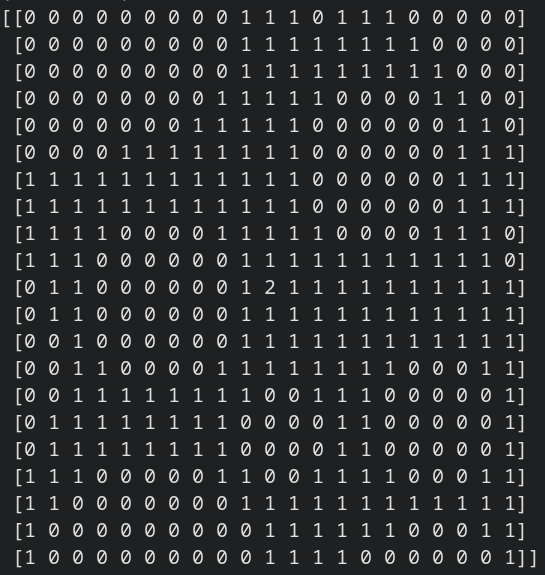

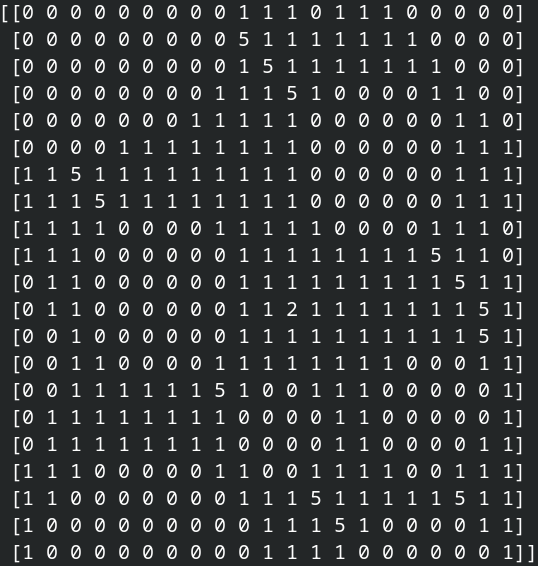

To start, I needed a representation of the map. I looked at the source code for the game page, but couldn’t easily figure out how to extract the map. So I started typing it into a spreadsheet:

I knew this would be slow and tedious, but the empirical slowness and tedium exceeded my expectations. After getting as far as shown above, I couldn’t take it anymore and decided to use image processing instead. I took a screenshot and then wrote a script that breaks up the image into tiles and then counts how many pixels in each chunk match the background color for water and for field. Then I manually added the horse. This gave me an array with 0 for water, 1 for field, and 2 for horse.

Enclosing the horse

Now, how to enclose the horse? How to formalize this as an instance of integer programming?

Thinking about this for a few minutes, I had the following thoughts:

Instead of thinking about if a given tile is enclosed, it’s easier to think about if it’s possible to escape from a given tile. Minimizing the number of tiles from which it is possible to escape is equivalent to maximizing the size of the horse’s enclosure.

So let’s have two binary variables for the solver to set each tile: (1) Is there a wall? (2) Is it possible to escape? The objective is to minimize the number of tiles from which you can escape. Say that

W[i,j]indicates if there is a wall at rowiand columnjwhileE[i,j]indicates if it’s possible to escape from that tile.Now all we need to do is add enough constraints to guarantee that the solution is valid.

There’s a maximum number of walls. So let’s constrain that the sum of

W[i,j]over alliandjdoesn’t exceed that.It must not be possible for the horse to escape. So let’s constrain that

E[i,j]=0for that tile.You can’t put a wall on top of the horse. So let’s constrain that

W[i,j]=0for that tile.For water tiles, it’s never possible to escape. So let’s constrain that

E[i,j]=0for those tiles.For field tiles on to boundary, it’s possible to escape unless there is a wall on the tile. So for

E[i,j]=1 - W[i,j]for those tiles.At field tiles not on the boundary, it’s possible to escape unless (1) there is a wall or (2) it’s impossible to escape from any neighboring tile.

Those thoughts can easily be translated into an integer programming problem.

Don’t believe me?

OK, I’ll give more detail. (If you do believe me, feel free to skip this section.)

Mathematically, our variables are W[1,1], ···, W[ROWS,COLS] and E[1,1], ···, E[ROWS,COLS]. These are all constrained to be zero or one. W[i,j]=1 indicates a wall at the tile on row i and column j, while E[i,j]=1 indicates that it’s possible to escape from the tile at row i and column j.

The objective is to minimize the number of tiles from which it’s possible to escape. That is, the goal is to minimize

E[1,1] + ··· + E[ROWS,COLS].There’s a maximum number of walls. For the above puzzle, it is 13. So we have the constraint that

W[1,1] + ··· + W[21,21] ≤ WALLS.It must not be possible for the horse to escape. And you can’t put a wall on top of the horse. For for whatever tile (i,j) contains the horse, we must have that

E[i,j] = 0,

W[i,j] = 0.It’s never possible to escape from water. So for all tiles (i,j) that have water, we must have that

E[i,j] = 0.For field tiles on the boundary, it’s possible to escape unless there is a wall. So for all field tiles (i,j) on the boundary,

E[i,j] = 1 - W[i,j].Finally, we’re left with the problem of enforcing the rules for escaping from the interior field tiles. Recall that the logic here is that you can escape unless there is a wall or it’s impossible to escape from any neighboring tile. Naively, if (i,j) is a non-boundary field tile, I’d have written the constraint as

E[i,j] = (1-W[i,j]) × max(E[i-1,j], E[i-1,j], E[i,j-1], E[i,j+1]).Taking a maximum is not linear, so integer programming solvers can’t deal with it. Fortunately, we can achieve the same thing by breaking it down into four separate constraints as

E[i,j] ≥ (1-W[i,j]) E[i-1, j],

E[i,j] ≥ (1-W[i,j]) E[i+1, j],

E[i,j] ≥ (1-W[i,j]) E[i, j-1],

E[i,j] ≥ (1-W[i,j]) E[i, j+1].Those are all the constraints. I claim that if any arrays E and W satisfy all those constraints, then the walls constitute a valid solution. I also claim that if you minimize the number of escapable tiles, then they constitute an optimal solution.

Still don’t believe me?

If you like your math formal and acerbic, here’s the full model:

Minimize:

∑ᵢⱼ E[i,j]

Subject to:

E[i,j] ∈ {0,1}

W[i,j] ∈ {0,1}

∑ᵢⱼ W[i,j] ≤ WALLS

E[i,j] = 0 if (i,j) is the horse

W[i,j] = 0 if (i,j) is the horse

E[i,j] = 0 if (i,j) is water

E[i,j] = 1-W[i,j] if (i,j) is a field on the boundary

E[i,j] ≥ (1-W[i,j]) E[i',j'] if (i,j) is a non-boundary field and (i',j') is adjacent

Drumroll

So I wrote some code to take the map as an array of integers and create all those constraints. Then I called scipy.optimize.milp. A fraction of a second later I had this solution, where I used 5 to indicate a wall.

Entering this into the website, it looked pretty good:

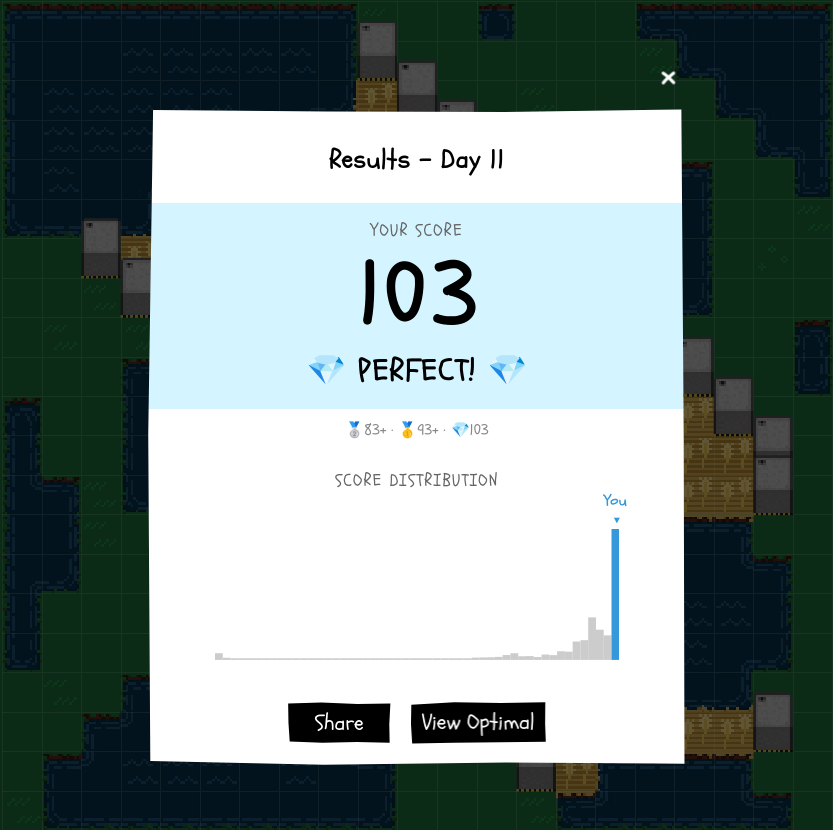

So I submitted the results, and...

As guaranteed by me / math / the solver, the solution was optimal.

For fun, I ran the same solver on all the previous days. Here I ran into some edge cases with the image processing for extracting the maps. Turns out, my computer slightly dims windows that aren’t focused, and the utility I was using to sample the colors for the website itself took focus. This took probably five times longer than everything integer-programming related and was extremely annoying.

But once the maps were extracted, the solver had no issues. It seems unsporting to show the actual solutions here, but these were the results. I manually entered all the solutions into the website to double-verify that they were optimal.

day solve time optimal?

1 0.062 s yes

2 0.964 s yes

3 1.190 s yes

4 0.091 s yes

5 0.280 s yes

6 1.948 s yes

7 3.826 s yes

10 4.536 s yes

11 1.142 s yesDays eight and nine had “cherries” that give extra points for being enclosed. Later days added “wormholes”. These are all extremely easy to deal with mathematically, but would have required even more image processing to get the maps, and I could not bear the thought of any more image processing.

If you want to see the code, please download the .CBZ file below and then change the extension to .ZIP. Inside you will find a single map image and a single 150-line python script. I know this is a stupid way to share code, but I’ve temporarily lost access to my main website. On the plus side, perhaps this will briefly prevent AI scrapers from training on my code?

Parting thoughts

Thought #1

Integer programming is magical. It really deserves to be considered a basic tool like grep.

Thought #2

How many NP-complete problems could be rendered “fun” to solve by hand with a sufficiently charming interface?

Well, many problems started as games and were only later observed to be NP-complete. This includes n-Queens completion, Nonograms and LaserTank. People empirically find these fun, so I guess we should classify them as fun.

But lots of other problems seem like they could be fun with the right interface. This seems plausible for Hamiltonian paths or graph coloring or the Chinese postman problem. Honestly, it was hard to find any that would clearly be non-fun. Maybe bipartite dimension or longest common subsequence? Those don’t seem fun to me, but given the large and vocal contingent of readers who insist that they enjoy going to the dentist, I suspect someone might enjoy them.

My best guess is that what makes a problem fun is a combination of two things:

Legibility. For a problem to be fun, you need to be able to sort of look at it and “feel” the mathematical structure you’re dealing with.

Difficulty. You should be able to almost solve the problem through broad heuristics like “put the walls in small bottlenecks” and only need to do a little bit of searching. Too hard or too easy, and it won’t be fun.

To put it another way, I think you should be able to mostly solve the problem using System 1 but need to engage System 2 enough to keep things interesting.

I make this guess on the basis that the ultimate non-fun problem to solve by hand is surely... integer programming? If I just give you a big list of variables and constraints, finding the optimum wouldn’t be fun at all, because your brain wasn’t designed to be good at manipulating big lists of numbers. It would be all search with nothing to understand or hold on to.

Thought #3

It’s not entirely obvious to me that enclose.horse actually is NP-complete. Just because you can use integer programming doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t find something that’s guaranteed to be fast. Though I’d bet against it.

Thought #4

Don’t play Factorio.

It seems to me this would allow a solution where a large space is bounded, and the horse was bounded separately? Am I wrong that there's nothing in your constraints which says that the inescapable area has to be attached to the horse?

Fun little game and I really want to try out integer programming now!

I think I've found a bug with your formalization: Have a look at this little level: https://enclose.horse/play/XHZO8P. I'm pretty sure the maximum score is 3. But your script's solution has a score of 1. It tries to enclose the upper row, which doesn't count as horse cannot reach it.

Edit: Yair Halberstadt was quicker in figuring this out