Is there a homeless crisis?

a look at the data

A few years ago, I took a look at the data on homelessness in the United States. We now have new data (and a new reality) so let’s revisit things, this time in superior list format.

1. After holding steady for years, homelessness recently jumped up a bit.

Here is the percentage of the population that was homeless between 2011 and 2023 (the last year we have data for):

There was a clear uptick after 2022. But this just brought things back to where they stood in 2011, which hardly seems like cause to panic.

To calibrate, here’s a comparison to some other rich countries:

All these numbers are the most recent data collected by the OECD. Take these numbers with a grain of salt—each country uses different methodology. I suspect this is particularly true for the “temp shelter” numbers (and thus also the totals). This suggests the United States is indeed on on the higher end.

Do things look more crisis-y if we look at certain states or cities? Or is the “type” of homelessness perhaps getting worse, with fewer people staying in a shelter for a few weeks while they find a new job, and more mentally ill people lingering for years on the streets?

2. It’s not noise.

First though, you might ask if the increase at the end of the above graph is real. Where are the error bars? The answer—at least in principle—is that there are no error bars, because we aren’t using an estimate of the number of homeless. It’s a full count.

Let’s back up. Every year in January, the US counts its homeless. Roughly speaking, how this works is that the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) tells hundreds of nonprofits and local government organizations across the country:

You there! Some night during the last 10 days of January, you must count every single homeless person in your area. If you don’t, then you don’t get any more money. How you accomplish this is your problem. Have fun!

HUD publishes the data and some vizualizations, but their $72 billion budget doesn’t provide for visualizations that are very good, so fine—I’ll do it.

3. Homelessness is much higher in some places.

Here’s the percentage of the population in each state that was homeless in January 2023. (The January 2024 count has already been done, but it takes HUD 11 months to publish the data.)

Those are percentages. So in Mississippi, 0.033% of people homeless, or 1 in 3300 is homeless. In New York, it’s 0.527% or 1 in 190.

4. Homelessness is increasing in some states, near constant in others, and decreasing almost nowhere.

When you talk about a crisis, theres an implication that things are getting worse. (You don’t hear much about the everyone you love will die and be forgotten “crisis”…) So here’s the change between 2020 and 2023, again as a percentage of each state’s population.

Broadly speaking, things are increasing in the West and Northeast and constant elsewhere. For example, in California, homelessness increased by 0.057%, or around 1 extra homeless person per 1750 people.

5. The biggest per-capita increase by far was in… Vermont?

Vermont increased by 0.336%. That increase alone is 2-3× the total homelessness rate in most states.

To be clear, the previous map is the change in homelessness as a percentage of the total state population. So this isn’t some artifact of having a small increase relative to an even smaller starting rate.

Some people seem to blame the increase on people moving to Vermont during Covid and causing increases in property values and/or the total number of people. Now, I’m normalizing the homeless counts for each state/year by the census’ per-year/per-state population estimates. That should control for increases in total population, but I haven’t really checked how accurate those estimates are.

My best guess is that it’s one of those “law of small numbers” things like how the countries with the highest rates of anything are always small countries: Vermont is tiny both in area and population (around 600k) so if something happens in one region, there isn’t some other unaffected area to average it out with. We’ll drill down to cities rather than states later.

6. There are different types of homelessness.

One person might run out of money, get evicted, stay in a shelter for a few weeks, and then eventually move in with family and get back on their feet. Another person might have mental health issues and linger on the street for years. If we want to understand things, we should try to distinguish which of these things is happening.

We’ll start on this by looking at two attributes that HUD collects.

The first is if someone is sheltered or unsheltered.They’re sheltered if they are staying in an emergency shelter, transitional housing program, or a safe haven. Someone is unsheltered if they’re staying in a vehicle, an abandoned building, or on the street.

The second is if someone is chronically or non-chronically homeless. Roughly speaking, someone is chronically homeless if they’ve been homeless for at least a year.

7. HUD’s formal definition of “chronically homeless” is ludicrously complex.

Technically speaking, according to their instructions, someone qualifies as “chronically homeless” if (a) they’ve been homeless for a total of at least one year in the last three years, (b) that homelessness happened in at least four separate episodes; and (c) those four episodes were separated by at least a week.

So someone who is 40 years old and has spent their entire life on the street except for Jan 1-6 of each year: Non-chronically homeless? Trying to apply this definition to everyone on a single night every year must be lots of fun.

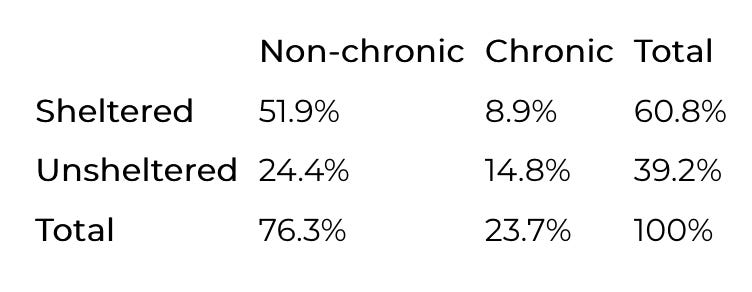

8. Most homeless people are sheltered and non-chronic.

Here is the breakdown at a national level:

How I think about this is:

The homeless are mostly non-chronic (around 3/4).

The non-chronic homeless are mostly sheltered (around 2/3).

The chronic homeless are mostly unsheltered (around 2/3).

Fine. But how has this changed over time. And how does it vary from place to place?

9. All types of homelessness have increased.

Until 2022, overall homelessness was holding steady, but getting “worse”—decreases in the “best” type of homelessness (sheltered non-chronic) were being offset by increases in the other “worse” kinds. But in 2023, all types increased.

10. Different states have different types of homelessness.

Let’s compare New York and California.

Though the overall homelessness rate is roughly similar in both places, California has much more unsheltered and chronic homelessness.

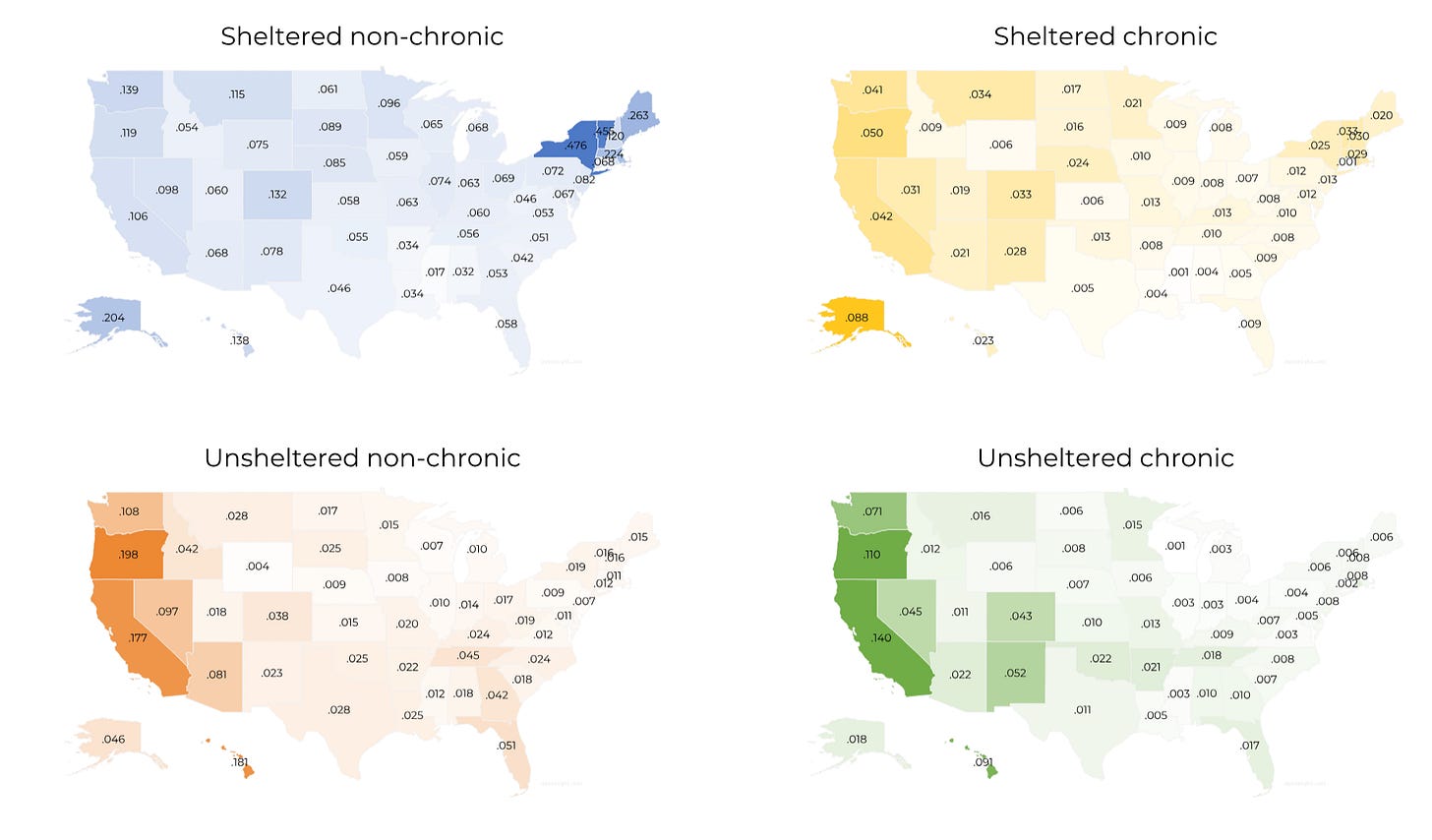

11. Sheltered non-chronic homelessness is highest in the Northeast. Unsheltered and chronic homelessness is concentrated in the West.

Here are maps for the percentage of each state’s population in each of the four states of homelessness.

The magnitudes vary by a lot. Sheltered non-chronic homeless make up 1 out of 5900 people in Mississippi but 1 out of 210 in New York. Unsheltered chronic homeless make up in 1 in 7000 in Minnesota but 1 in 936 in California.

When looking at these maps, let me remind you that this data is collected in January when it is cold in New York and stupidly cold in Minnesota. You have to imagine things would look quite different if data was collected in summer.

12. Sheltered non-chronic homelessness is increasing in the Northeast. Other types are increasing in the West.

Here is the change in each type of homelessness in each state between 2020 and 2023, where gray indicates a (rare) decrease, and a color indicates an increase.

To summarize:

Almost no states have declines in any type of homelessness.

The Northeast has increases in sheltered non-chronic homelessness.

Most states in the West have increases in unsheltered and/or chronic homelessness.

For even more detail, we can plot things for individual states year by year.

13. New York has recently had a huge spike in sheltered non-chronic homelessness.

After a decline from 2019 to 2022, there was a huge increase in 2023, presumably driven by the arrival of hundreds of thousands of foreign migrants.

Aside: Did you know that there is a constitutional right to shelter in New York? This is a result of a 1979 New York State Supreme Court decision. (This has recently been scaled back to 30 days.) Massachusetts also has a mandate from a 1983 law but only for families. The District of Columbia guarantees shelter to families, and to individuals when the temperature is below 32° F or above 95 °F (below 0° C or above 35 °C).

14. Increases in California are driven by unsheltered chronic homelessness.

15. Florida’s long decline seems to have ended.

After a long slow decrease, there was a small a recent increase. But of course, rates remain low.

16. HUD provides data on mental health, but it doesn’t make things easy.

Sheltered-ness and chronic-ness is one way to look into homelessness. But what about meth? What about mental illness? Many people believe these are a big part of the homelessness crisis.

Well, HUD does collect data on if people are “severely mentally ill” or suffer from “chronic substance abuse”. I can’t figure out exactly how these are defined. It’s implied that it’s done by literally asking people, but it’s also implied that it varies from place to place.

Anyway, though HUD collects these numbers, they don’t publish the data. However, they do publish reports, both for the entire nation, for individual states and for different local areas.

So I did the sensible thing. I downloaded 7372 different .pdf files, wrote a script to convert each .pdf to plain text, wrote a parser for that text, compensated for 8 billion infuriating inconsistencies in how they do all the reports, damn you HUD, damn you to hell, extracted the data on substance abuse and mental illness, and made plots.

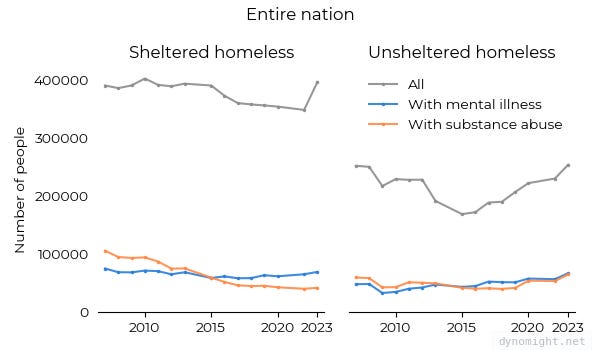

17. Nationally, there is a clear uptick in unsheltered homelessness with mental illness and/or substance abuse.

Blue is people with mental health issues, while orange is people with substance abuse. These are overlapping groups, although it’s not clear how overlapping. (My guess is it’s a lot.) Grey is all homeless people, including those without mental or substance abuse issues.

Take a look at the orange/blue lines in the bottom right of the above graph. This is a small fraction of the homeless population, but looms large as they tend to be more visible/disruptive. They’ve grown at quite a rapid rate since 2018 or so.

18. Things are even more pronounced in the West.

Here’s California:

That’s tens of thousands of extra unsheltered people with substance abuse issues since the minimum in 2018.

Washington state is even more stark:

19. But the pattern doesn’t hold in the Northeast.

Look at New York:

Or look at Massachusetts:

It makes sense that almost no one is unsheltered—it’s just too cold in these places in January. But then why don’t these states have increasing mental illness and substance abuse issues like the West? Is it because the cold forces people into shelters, and therefore more contact with supportive services? Highly unsure.

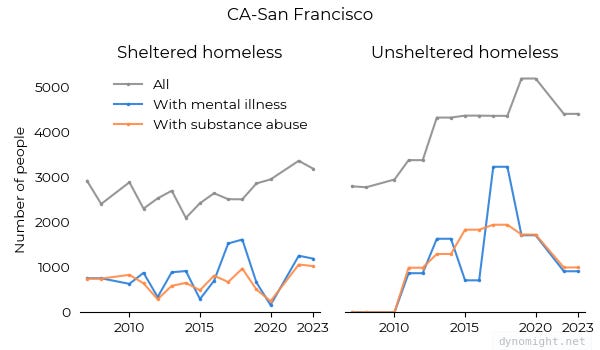

20. California is kind of confusing.

Here is the change over time in LA:

This fits with the previous narrative. But here’s San Francisco, the single place most identified with homelessness in the American imagination:

Huh?

I’ve made hundreds more plots with details for each state / city / region in the country. To view these, go here.

Very nice work!

Does New York being the epicenter of the migrant crisis have any influence on the statistics? I.e. are the illegal immigrants/migrants/asylum seekers/whatever-name-won't-raise-someone's-ire temporarily housed by the City of New York counted in the statistics?

https://www.sf.gov/news/new-data-san-francisco-street-homelessness-hits-10-year-low

There is a big program to reduce unsheltered homeless. I am glad it is making progress.

They are also stepping up enforcement, so I wonder if some of the decrease is caused by the chronically unsheltered moving to other towns.