Fahren-height

(celsi-pour?)

The Internet is well into middle-age, and yet doesn’t seem to have answered humanity’s most pressing question: If you pour boiling hot water from various heights, how much does it cool in flight?

First attempt

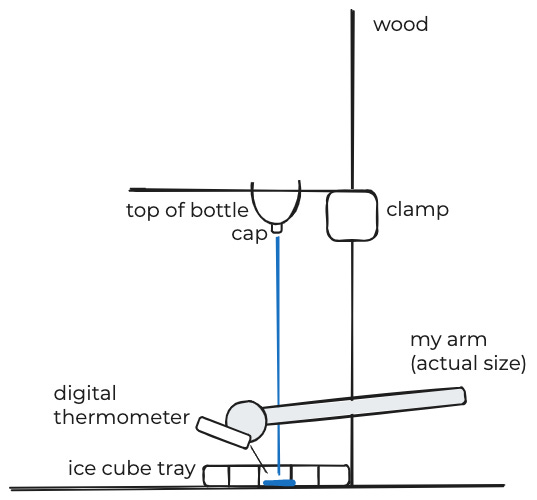

I figure there are two key variables: The height you pour from, and how fast you pour. To control for both of these, I built this little apparatus:

To get different heights, I cut off the top off a 2-liter bottle and drilled two holes in it. I then shoved the end of a clamp through the holes and clamped the clamp to four positions on a plank of wood.

To get different pour speeds, I took three bottle caps, and drilled different-sized holes in them.

Finally, for each height/cap-width combination, I poured some boiling water into the funnel and let it fall into a silicone ice-cube tray. I measured the peak temperature with a digital thermometer, being careful to allow the scalding-hot water to splatter onto my unprotected hand.

First results

I took five measurements in each setting. Here it is with a bit of horizontal jitter when needed to avoid overlap.

This data is quite noisy. My guess is that’s because there’s some surface tension that helps water cling to the bottom of the cap. This makes the stream of water jiggle around chaotically. (This looked the most random at higher heights, though that doesn’t appear to show up in the measured temperatures.)

Here’s a quadratic fit for each of the three cap sizes:

While the offsets vary, the shapes of these curves are pretty similar. So we can summarize these experiments like this:

Pouring from even a very low height cools water by 3 to 13 ºC, depending on the pour speed.

Pouring from 25 cm (10 in) gives an additional 1-2 ºC.

Pouring from 60 cm (24 in) gives an additional 5 ºC.

Also: If you conscript the people you live with into helping you with this experiment, you may find that proposing to repeat it at 100 cm results in shrieks of dismay (“please don’t pour another 10 liters of boiling water onto our counter” etc.) which are not conducive for Important Science.

Second Attempt

But how does this correspond to the real world? I decided to do a second experiment pouring water out of a kettle by hand. This time I used the clamp to hold the thermometer:

I tried to pour at different speeds, but it was hard to be consistent. So I just measured how long it took to fill the (250 ml) cup. Here’s the data:

And here’s a linear fit for each of the three heights:

(I don’t know why there’s no confidence interval for the 8 cm data.)

Finally, I fit a regression. The final fit was

(temp) = 98.0 - 0.21 × (height) - 0.37 × (time),

where (temp) is in ºC, (height) is in cm, and (time) is the number of seconds needed to pour 1 cup (250 ml).

For example, say you pour a liter of boiling water from a height of 10 cm at a rate where it takes you 20 seconds to pour the full liter. That’s equivalent to 5 seconds per 250 ml, so this formula predicts the final temperature will be around

98.0 - 0.21 × 10 - 0.37 × 5 ≈ 94 ºC.

Conclusion

Pouring from higher heights can make water significantly cooler. But to get much cooling from extra height, you need quite a lot of height—so much that you’d have to be very coordinated (or crazy). So for most people, your best bet is probably to pour slowly, to pour into a thick mug so the thermal mass can neutralize more of the heat, or (horror) to wait.

Notes

It turns out that 1 plastic ♲ does not melt when exposed to boiling water, though it does become very soft.

To cool the funnel between measurements, I poured some room temperature liquid through it. To the horror of the Dynomight Biologist, the closest liquid on hand happened to be a pot of expensive insect-bitten tea that I’d brewed a day earlier and not consumed. It’s hard to be sure what the insects would think about this.

Thank you for reading my middle-school science fair project.

The "insect-bitten tea" link doesn't work for me.

In India in the 1940s and 1950s (and for all I know possibly still today..) one used to be able to buy a cup of tea on railway platforms, whilst the train was stopped at the station. Because the water came out of the tea urn boiling hot and you were going to drink it from a heat-conducting tin mug (and only had a few minutes whilst the train was stopped) the tea urn man would cool the tea for you by pouring it between two receptacles before pouring it into your tin mug.

Rather than pouring from an extreme height he would pour it several times back-and-forth, and rather than trying to "aim" the pour he would begin the pour with the two receptacles held close together, one in each hand, then (with practiced swiftness) raise one up whilst keeping his eyes on the lower one to keep the stream roughly in the centre of its opening. Then he'd bring the two receptacles back together, all the while "connected" by this stream of tea, and pour back to the first one. The whole process looked a bit like somebody stretching out some ductile, toffee-like substance between their hands.

[Also: to know how significant your results are, I'd love to know what temperature the water started off at? (ie. what was the ambient pressure in the room it was boiled in, and was boiling-point measured visually, by thermometer, or by a steam-pressure-switch like you'd find in a kettle..?)]