Ethylene for fun and profit and produce

Amos answered Amaziah, “No prophet am I, not any prophetic symbol, but a shepherd am I, who used to prick the sycamore fruit that it might duly ripen for the market.”

— Amos 7:14 (translated by Samuel Cox)

While I’d like to understand the world, reality isn’t structured to make that possible. Powerful big ideas are great, but inevitably you need to look at the details, and those connect to other details and it branches out forever. The chasm between this complexity and the meager capabilities of my human brain/lifespan gives me a constant feeling of dread and wonder.

To cope with this, I sometimes do random sampling—pick a thing and obsessively follow the links until I’m defeated.

So, umm, here’s the first in a series of posts about a plant hormone called ethylene. I got interested in this with the mundane hope of keeping my fruits and vegetables from going bad but ended up with some lessons about biology, public health, supply chains, capitalism, and ancient Greek prophecies.

Ethylene is a gaseous plant hormone.

Our story is about two atoms of carbon and two atoms of hydrogen glued together as C2H4.

Ethylene is a colorless gas that smells sweet and musky. It acts as a hormone on plants, giving it effects on things like:

fruit ripening

changing colors (chlorophyll destruction)

flower development

root formation

production of chemicals that defend against pathogens called phenylpropanoids

how much ethylene plants produce

Ethylene is active at low concentrations, typically ranging from around 10 parts per billion to one part per million (Chang 2016).

It has interesting origins

Chang (2016) makes the following remark:

It is believed that plants most likely acquired the ethylene receptor gene from an ancient endosymbiotic cyanobacterium that became the chloroplast.

A biologist might yawn. For the rest of us, this sentence tells an amazing story:

Long ago, plant cells couldn’t do photosynthesis.

Instead, it was done by an independent bacterium that symbiotically lived inside of plants.

That bacterium had an ethylene receptor gene.

At some point, that gene somehow managed to make its way from the bacterium into the plant genome.

Later on, the bacterium evolved into being the part of the plant cell we know as the chloroplast.

Because of this independent origin, the chloroplast has its own DNA, much like mitochondria do in animal cells.

Wow dude, wow.

Many didn’t believe a gas could be a hormone.

You might ask: Isn’t it a crazy idea to use a gas as a hormone? Well, there’s an interesting story about that.

First, what is a hormone exactly? In 1905, Ernest Starling defined a hormone as a chemical that’s:

made in small quantities in one part of a multi-cellular organism

has effects on a distant part of that organism

Around 1860 people noticed that gas lights led to weird (mostly bad) effects on plants. After a lot of research, 1901 Dimitry Neljubow finally identified ethylene as the active agent. But this didn’t show ethylene was a hormone. For one, hormones weren’t defined yet. More importantly, it wasn’t known that plants make ethylene.

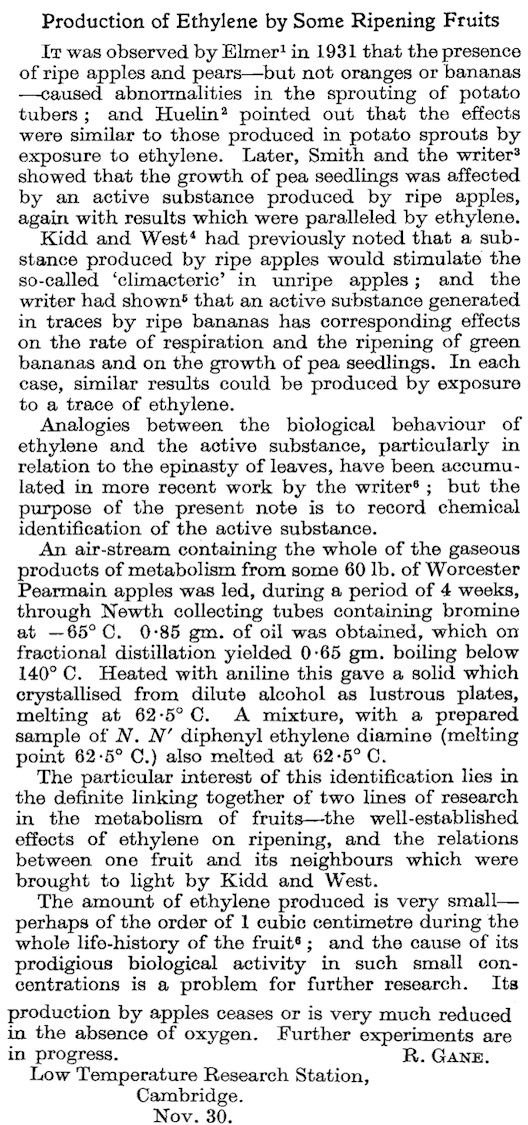

In 1910, Herbert Cousins—who only has a Wikipedia page in German—noticed that if a fungus was applied to oranges, they release a gas that causes bananas to ripen. It was only in 1934 that Richard Gane finally showed that apples synthesize ethylene.

(The article is 6 paragraphs long. The times have changed, oh how they have changed.)

At first, many people rejected the idea that a gas could be a hormone, but similar experiments soon showed that many other plants also make ethylene.

Now, if ethylene is a gas, doesn’t that mean it naturally drifts around, meaning plants can be manipulated by nearby plants? Well, yes. Many common fruits like apples, bananas, and avocados produce large amounts of ethylene, which has massive effects on other produce. Now, evolution doesn’t explain her choices to us, so it’s debatable to what degree this is “intentional”, especially when it happens across species. But arguably, ethylene should be considered a pheromone, not just a hormone.

Humans have manipulated ethylene for a long time.

For thousands of years, people have pricked fruits (e.g. Amos’ sycamores) because that causes them to produce ethylene and thus ripen. Various traditional cultures used smoke to ripen fruit, which works because smoke contains ethylene.

These days, humans manipulate ethylene on an industrial scale. We expose produce to ethylene gas and spray ethylene precursors on plants. Or when we don’t want the effects, we scrub ethylene from the air or spray chemicals that inhibit ethylene response. We even genetically engineer plants to screw with how they produce and respond to ethylene.

Now, when humans manipulate ethylene, why are we sometimes trying to increase it and sometimes trying to decrease it? Because…

Effects are sometimes good and sometimes bad.

The major good effects of ethylene are ripening, color development, and de-greening in citrus. There are also some obscure effects.

It helps nuts split from their hull. This is called “dehiscence” but I implore you not to go searching for that term unless you enjoy traumatizing panoramas of human wounds.

It can manipulate sex expression in cucumbers, melons, and pumpkins. Did you know that plants can be trimoneocious, i.e. have male and female and hermaphrodite flowers? I can’t figure out exactly why manipulating sex expression like this is good, but food scientists seem very excited about it.

The same effect might be good or bad, depending on the situation. Ripening fruit is good if it’s immature, but not if that causes it to rot before someone eats it. Making a plant produce phenylpropanoids is good if it needs to fight off pathogens, but bad if it makes food taste bitter. Chlorophyll loss is good for oranges when it makes them look orange, but terrible for broccoli when it becomes yellow and ugly.

To answer if ethylene is good or bad for any particular plant, we need a bit of background.

There are two types of fruit.

Fruits are classified as climacteric or non-climacteric. The difference is that during the final ripening stage, climacteric fruits have a dramatic burst of CO2 and ethylene production. Here’s a figure from Paul et al. (2011):

Here’s a list of fruits.

Climacteric: apple, apricot, avocado, banana, bitter melon, blueberry, cantaloupe, durian, kiwi, mango, nectarine, passion fruit, peach, pear, plum, tomato

Non-climacteric: berries (except blueberry), citrus, cucumber, eggplant, grape, lemon, lychee, mandarin, melon (except muskmelon), olive, peppers, pineapple, pumpkin, summer squash

To understand what ethylene does, we need to understand two things. First, what effects does ethylene have? Broadly speaking, the story is:

In climacteric fruit, ethylene will cause ripening.

In non-climacteric fruit and vegetables, ethylene will either have bad effects or just won’t do anything.

Second, how much ethylene will plants produce? This depends on:

Species. Climacteric fruits produce a lot, non-climacteric fruits and vegetables produce much less.

Time. Climacteric fruits produce much more right around when they are ripening.

Stresses. Things like pathogens or wounding increase ethylene production.

Temperature. Generally, plants emit less ethylene when colder. However, temporary extreme temperatures (high or low) can also sometimes act as a kind of stress and increase ethylene production.

Be careful what you store together.

Bored of all this theorizing? Just want to know where to put stuff in your kitchen?

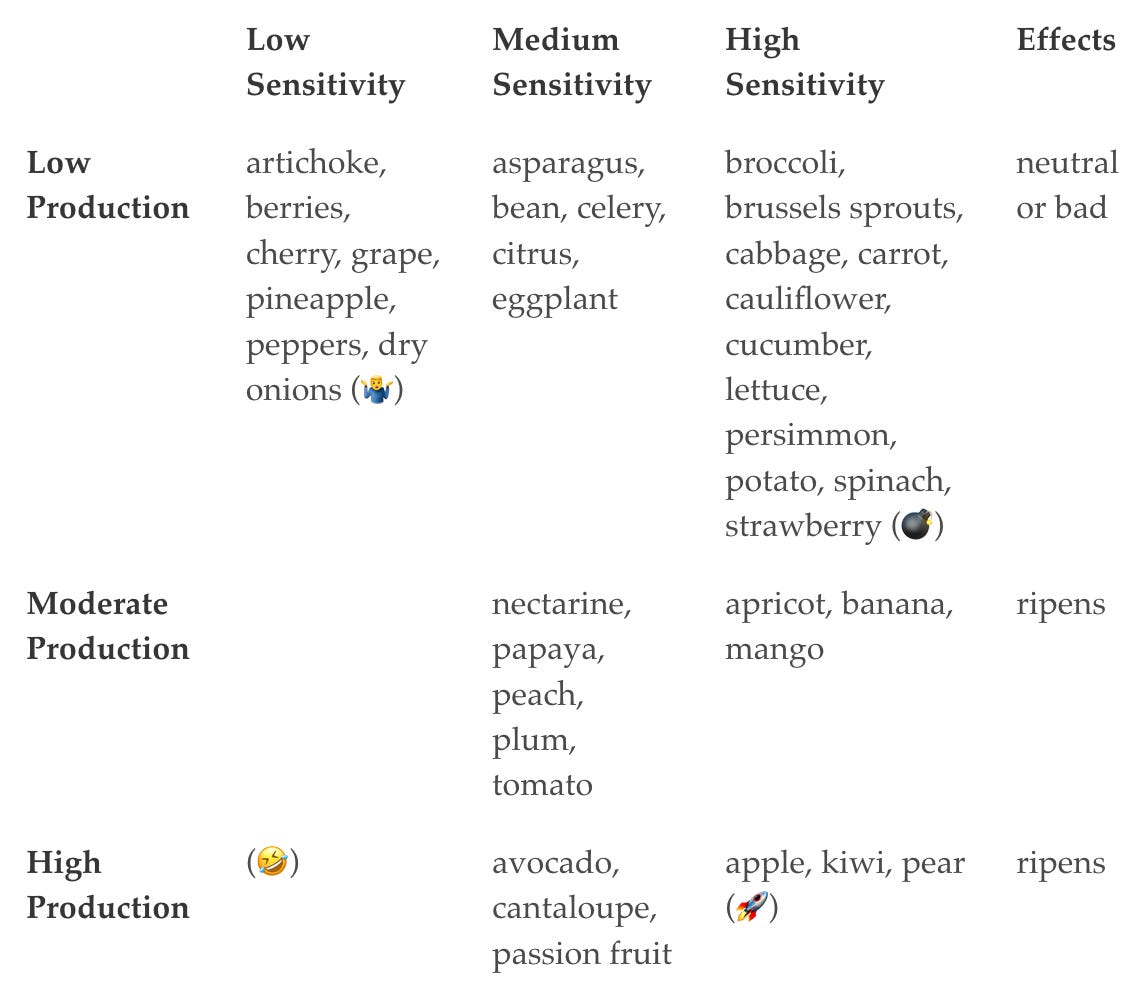

Here’s a table that classifies produce by ethylene production and ethylene sensitivity, modified from Fennema’s Food Chemistry (Table 16.17).

I kept getting confused when looking at this table, so I added emoji to try to remind myself of what the four corners are:

🤷♂️ — “I don’t care about ethylene” (Low production and low sensitivity)

💣 — “Potential disaster” (Low production and high sensitivity.)

🤣 — “Enjoy all my ethylene lol” (High production and low sensitivity.)

🚀 — “Go go go go” (High production + high sensitivity)

Everything in the top row is a vegetable or non-climacteric fruit, while everything in the bottom two rows is a climacteric fruit. Roughly speaking, this means that for the top row, ethylene will be neutral or bad, while for the bottom two rows it will ripen stuff. (Though see the discussion on citrus.)

Refrigerators often have high ethylene levels.

Wills et al. (2000) measured ethylene in the crisper of the refrigerators in 30 households in Australia. They found 17% had low levels (≤ 0.015 ppm), 30% had high levels (≥ 0.10 ppm), and the rest were in the middle. (Recall that a level like 0.1 ppm typically produces a half-maximal response.)

The most important predictor of high ethylene levels was apples. The mean level in refrigerators with apples was 0.2 ppm, compared to only 0.029 ppm in those without.

Dilemma: Should you store apples in the refrigerator?

So, apples in the refrigerator will raise ethylene levels. This is bad if you have stuff like broccoli that’s ethylene sensitive. On the other hand, refrigerators lower the temperature of the apples themselves, which will decrease ethylene production. On the other other hand, refrigerators have little ventilation, meaning the ethylene that is produced will tend to stick around nearby. So even if all you had was apples, it isn’t obvious if refrigerating them would be a net positive or a negative.

My tentative recommendation is to not refrigerate apples. They last a reasonably long time even when not refrigerated, so I don’t think it’s worth the risk they pose to your other produce.

This dilemma becomes much trickier when you’ve got something like avocados that both produce ethylene and go bad quickly. There, I’m not sure what to recommend. (Just eat them faster?)

Myth: It’s bad to store onions near potatoes.

Here’s something you often hear:

Onions and potatoes shouldn’t be stored together because they produce a gas that will cause the other to sprout.

Often the gas isn’t specified. But if it is, people point to ethylene.

I think this is a myth. At least, if it’s bad to store them together, ethylene isn’t why. Recall:

Potatoes don’t produce much ethylene but are sensitive to it.

Onions don’t produce much ethylene, and also aren’t sensitive to ethylene.

What’s bad is storing potatoes near ripe apples/pears/bananas/etc.

So why do people say it’s bad to store potatoes near onions? Because onions like to be stored colder than potatoes, or because they’re both sensitive to humidity, or because everyone is just wrong. (See this comment for some wonderfully obsessive research.)

No one knows what ethylene concentrations happen in a paper bag.

A classic grade-school science experiment is to put some fruit in a paper bag with ripe bananas and show that it ripens faster.

While this clearly works, I wanted to know: What concentration of ethylene does this create? After spending way too much time searching, I’m pretty sure no one knows the answer. The problem is that measuring ethylene concentrations in air is expensive because you need fancy equipment that would cost a minimum of $15k. (If you’ve some gas chromatography or nondispersive infrared spectroscopy equipment lying around and you want to resolve this vital question… get in touch.)

Ethylene removal products don’t seem to help.

You can buy stuff that’s supposed to absorb ethylene. In theory, this should help preserve stuff longer, but in practice, they don’t seem to help much.

Debbie Meyer GreenBagsⓇ are plastic bags that are supposed to absorb ethylene. Consumer reports, as well as various local television stations, have done tests that overall found they didn't do much, and were sometimes worse than using a regular plastic bag

The BlueappleⓇ is an ethylene absorbing sachet that you put inside of a piece of plastic designed to feel like Science. The few tests I could find showed little benefit.

I suspect is that these products do absorb ethylene as claimed, but the effects just aren’t big enough to rise above random variation. Also, you’d typically use these things in confined spaces which limits airflow—this could be harmful on net.

Still, I commend the idea. Some fancy refrigerators have built-in ethylene scrubbers, though I haven’t been able to find any clear evidence that any specific products really help in practice.

Also, regular ultra-cheap activated carbon absorbs ethylene just fine (Gaikwad et al. 2019), so maybe you could try to just brute-force the problem that way. (Another opportunity for someone with free time and spectroscopic sensors.)

Next post, coming soon: How the food industry manipulates ethylene