Datasets that change the odds you exist

Stats for dangerous situations

1.

It’s October 1962. The Cuban missile crisis just happened, thankfully without apocalyptic nuclear war. But still:

Apocalyptic nuclear war easily could have happened.

Crises as serious as the Cuban missile crisis clearly aren’t that rare, since one just happened.

You estimate (like President Kennedy) that there was a 25% chance the Cuban missile crisis could have escalated to nuclear war. And you estimate that there’s a 4% chance of an equally severe crisis happening each year (around 4 per century).

Put together, these numbers suggest there’s a 1% chance that each year might bring nuclear war. Small but terrifying.

But then 62 years tick by without nuclear war. If a button has a 1% chance of activating and you press it 62 times, the odds are almost 50/50 that it would activate. So should you revise your estimate to something lower than 1%?

2.

There are two schools of thought. The first school reasons as follows:

Call the yearly chance of nuclear war W.

This W is a “hidden variable”. You can’t observe it but you can make a guess.

But the higher W is, the less likely that you’d survive 62 years without nuclear war.

So after 62 years, higher values of W are less plausible than they were before, and lower values more plausible. So you should lower your best estimate of W.

Meanwhile, the second school reasons like this:

Wait, wait, wait—hold on.

If there had been nuclear war, you wouldn’t be here to calculate these probabilities.

It can’t be right to use data when the data can only ever pull you in one direction.

So you should ignore the data. Or at least give it much less weight.

Who’s right?

3.

Here’s another scenario:

Say there’s a universe. In this universe, there are lots of planets. On each planet there’s some probability that life will evolve and become conscious and notice that it exists. You’re not sure what that probability is, but your best guess is that it’s really small.

But hey, wait a second, you’re a life-form on a planet with conscious life! Given that you exist, should you increase your guess for how likely conscious life is to evolve on a random planet?

Again, you have two schools of thought. One says yes, you have data, increase your guess, while the other says no, don’t increase, if there wasn’t life you wouldn’t be here, anthropic principle—anthropic principle!

4.

After many years of being confused by these questions, I think I now understand what’s happening. These questions are confusing because they’re actually about a sort of narrow technical question, and only appear to be about to the fact that you might not exist.

To explain, let me introduce another scenario:

One day you wake up at my house. As you groggily look around, I explain that you’ve been invited to Dynomight family dinner! And that the way that DFD works is:

I sneak into your house at night, anesthetize you, and bring you to my lair.

When you wake up, I make you some delicious Fagioli all’Uccelletto.

After you’ve eaten, I bring out a box containing a bunch of identical revolvers. Half have no bullets in them, while the other half have bullets in all six chambers. You pick one revolver at random, put it to your head, and pull the trigger. (To refuse would be a huge faux pas.)

If you’re still alive, I bring out a $100 bill and offer to sell it to you for $60. If you agree, I take your gun and see if it has bullets in it. If it’s empty, then I take your $60, give you the $100, and ask you to come back soon. If not, I take your $60 but don’t give you the $100, welcome to dinner at my house, chump.

So you eat the Fagioli all’Uccelletto (it is excellent) and you play the mandatory revolver game and don’t die, and I offer you the $100. Should you accept?

Yes you should. There’s no trick. Since you’re alive, you know your revolver is empty, so you’re guaranteed to make a free $40.

5.

Fine. But now consider the same scenario, with two small changes (in bold):

I sneak into your house at night, anesthetize you, and bring you to my lair.

When you wake up, I make you some delicious Fagioli all’Uccelletto.

After you’ve eaten, I bring out a box of identical revolvers. All have three chambers with bullets and three empty chambers. You pick one revolver at random, put it to your head, and pull the trigger. (To refuse would be a huge faux-pas.)

If you’re still alive, I bring out a $100 bill and offer to sell it to you for $60. If you agree, I take your gun and look at a random chamber. If that chamber is empty, then I take your $60, give you the $100, and ask you to come back soon. If not, I take your $60 but don’t give you the $100, welcome to dinner at my house, chump.

Should you accept?

No. You know that all the revolvers have bullets in half of their chambers. The fact that yours didn’t go off doesn’t change that. If you accept my offer, then you have even odds of gaining $40 or losing $60. That’s a bad bet.

6.

So what does all that have to do with the odds of nuclear war?

I claim that arguments about if you should update your estimate of the risk of nuclear war are equivalent to arguments about which version of Dynomight family dinner you’ve been invited to.

And note—the fact that you might stop existing is irrelevant. Instead of putting the gun to your head, say you fire it into the ground and if it goes off, you just go home. Nothing changes!

Or, hell, replace the revolvers with happy puppy bags and replace full/empty bullet chambers with red/blue marbles. Again, nothing changes.

The crux of the nuclear war scenario isn’t that you might stop existing. That’s just a very salient feature that draws our attention away from the heart of the debate: The confidence of your prior.

7.

When you guess that there’s a ~1% chance of nuclear war, what does that mean? One option is that you’re sure that the chances are exactly 1% per year. Alternatively, you might think that the chances could be anything from 0% to 5%, but your average guess is 1%.

The general way to think about this is to create a “prior”—to draw a curve of how plausible each yearly chance of nuclear war is.

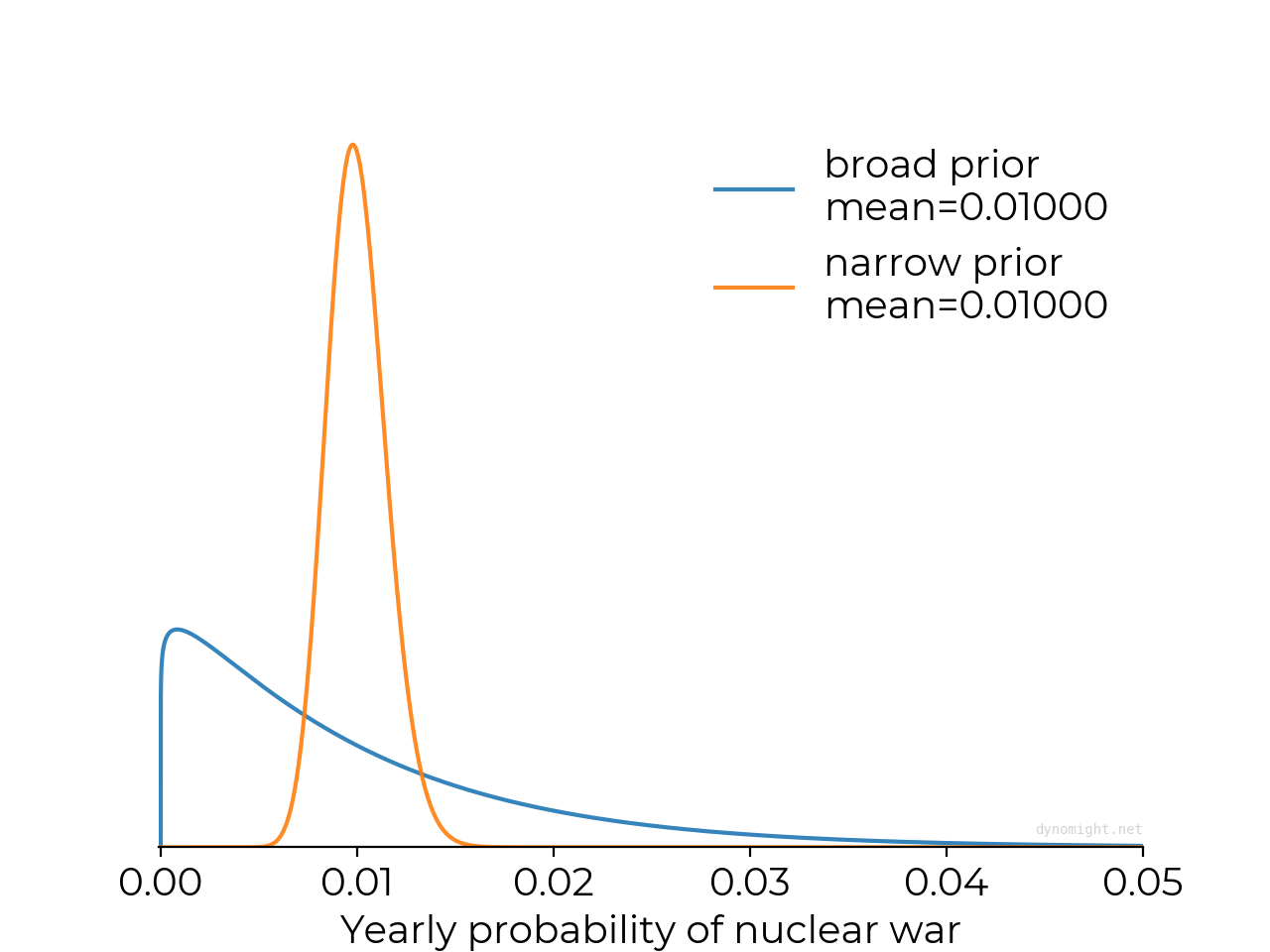

Ask yourself, which of these two priors is better?

If you choose the narrow (orange) prior, then you’re sure that the chance of nuclear war is quite close to 1%. If you choose the broad (blue) prior, then you’re very unsure. In both cases, the mean is 0.01 (or 1%). But the amount of uncertainty is totally different.

Now, think about the fact that 62 years went by without nuclear war. You can picture this as a “likelihood”—for each possible yearly chance of nuclear war, how likely is it that you’d see 62 years without war?

If the yearly probability of nuclear war is 0, then after 62 years, you’re guaranteed to avoid nuclear war. The higher the yearly chance of war, the less likely this is to happen.

To get your “posterior” belief after 62 years, you just multiply your chosen prior with the likelihood at each position on the x-axis. Here are the posteriors for each of the above priors. (Corresponding priors shown with dotted lines for reference.)

The more confident your prior, the less open-minded you are about changing your mind after you see data.

In the above graph, the broad prior shifts to the left in the posterior. The narrow prior also shifts a bit to the left but only a tiny amount—the prior is so concentrated that the data can hardly budge it.

With the broad prior, the data moves the best guess from 1% to around 0.637%. With the narrow prior, it only moves to 0.986%. In the limit of a totally confident prior (an infinitely tall, infinitely narrow “spike”) the data wouldn’t move things at all.

8.

So how are you supposed to think about the risk I nuclear war? I claim you should treat it just like any other situation: You state a prior and then update it based on whatever data you have. The fact that we might not be here with different data is irrelevant.

The question is if we should have a narrow or a broad prior. For the specific case of nuclear war, I don’t see how you could be sure that the odds are almost exactly 1%. (Or whatever.) The geopolitical dynamics that might lead to nuclear war are waaaaaaay too complicated. So I think any reasonable prior should have significant uncertainty, and the fact that nuclear war hasn’t happened yet means we should revise our estimates down a bit.

But just a bit. If we survived another 1,000 years without nuclear war, then that would really prove something. But 62 years isn’t that long, and only calls for a small adjustment.

9.

If you’re still not convinced, consider one last scenario:

Take two identical-looking happy puppy bags:

Fluffles contains 9 blue marbles and 1 red marble.

Snowcone contains 1 blue marble and 9 red marbles.

You pick one happy puppy, look at one random marble, and put it back.

I offer you a deal: If you give me $50, then I will open your happy puppy and give you $10 for each blue marble.

Should you take the deal?

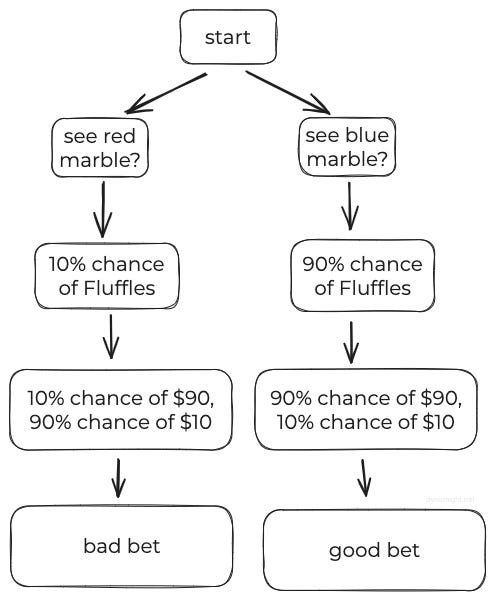

Don’t stress about the math. You can picture this situation like this:

As you’d expect, a blue marble means you’ve probably got Fluffles, so you should take the deal. A red marble means you’ve probably got Snowcone, so you shouldn’t.

Fine. But say that if you see a red marble, then you go home and aren’t offered a bet (or, if you like, say I kill you). Then you can picture the situation like this:

If you see a red marble, game over. But if you see a blue marble, you make decisions exactly like you did before. What might happen for some other dataset doesn’t change the best decision for your dataset.

10.

Say I take up free solo chainsaw juggling. You think this is a stupid hobby, but I do it every weekend for a few months without any accidents and then tell you, “Hey, look, I’m fine, this is perfectly safe.”

Are you wrong to say, “If you’d died, you wouldn’t be here.”?

I don’t think so. But I think what you really mean is (a) there are strong prior reasons to believe free solo chainsaw juggling is dangerous, and (b) the fact that I’ve survived for a few months isn’t enough evidence override that prior. So let’s quit the free solo chainsaw juggling.

Enjoyed this but might add that it seems to me quite misleading to think of probabilities as inherent properties of the world; Probability is a conceptual tool we use to reason about the world. There isn't an underlying truth of "likelihood of nuclear war" though in certain cases it can be quite handy to think of it this way.

see e.g. https://metarationality.com/small-world

This is essentially the question raised (and discussed at length in the philosophy literature) by the sleeping beauty paradox.

In terms of pure decision theory for you personally, I think everything you said is fine. The problem is that's not the only way we use probability talk -- indeed I suspect that the way we use probability talk conflates two different ideas.

Basically the idea in sleeping beauty is that you are drugged into unconsciousness on Sunday and your captor flips a coin. If the coin is heads the captor wakes you up on Monday then wipes your mind and lets you go. If the coin is tails the captor wakes you up on Monday, wipes your memory and redrugs you and wakes you up again on Tuesday.

Suppose you wake up in the captor's possession one morning and the captor explains the situation (but not what day it is) what should your probability be the coin landed heads? Well it seems obvious it's 50% but now suppose you know the captor will offer you a $100 bet every time you wake about whether the coin landed tails at just below even odds.

Obviously you should take the bet because if the coin lands tails you will win twice but if it lands heads you lose once. That suggests you should assign probability of tails to be 2/3rds.

Ultimately, I think the confusion is over which of two questions one is answering (probability is just fancy counting). Are you trying to count up the situations from your perspective or from some kind of imagined 3rd party perspective?

To put it roughly in another way, there are an equal number of 'ways' the universe turns out where the captor gets a head and a tails. However, there are twice as many 'ways' you wake up in said situation with the coin tails as heads. So it's all just about what you are counting.