The real data wall is billions of years of evolution

Careful with those human analogies

Say you have a time machine. You can only use it once, to send a single idea back to 2005. If you wanted to speed up the development of AI, what would you send back? Many people suggest attention or transformers. But I’m convinced that the answer is “brute-force”—to throw as much data at the problem as possible.

AI has recently been improving at a harrowing rate. If trends hold, we are in for quite a show. But some suggest AI progress might falter due to a “data wall”. Current language models are trained on datasets fast approaching “all the text, ever”. What happen when it runs out?

Many argue this data wall won’t be a problem, because humans have excellent language and reasoning despite seeing far less language data. They say that humans must be leveraging visual data and/or using a more data-efficient learning algorithm. Whatever trick humans are using, they say, we can copy it and avoid the data wall.

I am dubious of these arguments. In this post, I will explain how you can be dubious, too.

The math checks out—humans see much less language data

Every day, an average person reads a few thousand words, and hears perhaps 16 to 40 thousand. So a well-educated 40-year old might have encountered 5×10⁸ words in their lifetime. Recent language models are trained on upwards of 10¹² 10¹³ words—200,000 times more. It’s not even close.

Imagine a fast reader who did nothing but read 300 words/minute for 80 years, never pausing to eat or sleep. They’d still see 1000 times fewer words than AIs do.

Vision is not the key to human intelligence

So then how do humans generalize so well from so little language data? Is “pre-training” on visual data the secret to our success?

No.

Because… blind people? What are we doing here?

Deaf people show that (non-verbal) sound isn’t critical either.

Could it be touch? There is a disease called congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis or CIPA. People with CIPA often have intellectual disabilities, but much of that is surely due to the (horrible) consequences of CIPA or the protein misfolding issue that causes it. And anyway, many people with CIPA have normal intelligence. Miall et al. (2021) describe a person known as “KS” who is not paralyzed but has had no sense of touch at all since birth. They don’t do any IQ tests, but do mention that KS graduated from law school.

It seems unlikely that intelligence would be based on smell or proprioception.

Maybe we need vision or sound? At first, I thought Helen Keller was a counter-example to this. Clearly she was very smart, but she apparently had sight and hearing before losing them to meningitis at the age of 19 months. Other people are deafblind since birth. They often have intellectual disabilities, but Larsen and Dammeyer (2020) report that many don’t if given early access to language though tactile signing. However, they only report the fraction of people with IQs above 70, and I can’t tell if anyone born deafblind went on to have an average IQ.

Now, don’t write off other modalities. It could be that human brains are so adaptable, that we just need exposure to language plus some kind of high-resolution sensory data. Or maybe it’s critical that we interact with our environment. We have no examples of paralyzed people with no senses that somehow survive and passively absorb language for decades.

Maybe! Or maybe all that other sensory data is irrelevant. I don’t know. But that’s kind of the point—the example of humans just isn’t very useful for predicting how helpful other modalities might be for AI.

Humans get information from evolution

Many comparisons between humans and AIs seem to be based on the following analogy:

AI systems “learn” from data.

Human babies “learn” from experience.

The issue with this analogy is that humans are born with extremely sophisticated programming, provided by evolution. That programming integrates information from all our ancestors, arguably going back to the origin of life on earth.

When you train an AI, you have to learn lots of stuff that babies get “for free”. Your intelligence is based on “data” from your whole evolutionary history, not just your lifetime.

Now, a skeptic might accept that human babies get some information from evolution, but object that it can’t be much information. After all, a single month of CommonCrawl (used by all current models) is around 200 terabytes. Yet human DNA has around 2.9 billion base pairs, each of which can take 4 values. That adds up to only around 6 billion bits or 690 megabytes. That’s 30,000 times less.

And DNA has lots of other jobs beyond intelligence, like making ribosomes or making teeth or running an immune system. Is DNA too small to matter?

DNA is not that small

Your DNA probably contains more information than all the words you’ll encounter in your whole life.

Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, famously estimated that English language text on average has 11.8 bits/word. But recent language models suggest that it’s only 2.3 bits/word or perhaps even less. So the 5×10⁸ words a person might have heard probably only contains 1.2 billion bits of actual information—less than the 6 billion bits in DNA.

(People used to think that most DNA was “junk” because it didn’t directly code for proteins. But research increasingly suggests it plays other important roles, like determining how DNA folds or regulating the expression of other genes. This is an active research area with credible people on both sides. I’ll stick with 6 billion bits for simplicity.)

Now a modern AI dataset of 10¹³ words surely does contain much more information than DNA—perhaps 3800× as much. But a big fraction of that is things like, “to cure all health problems, buy CBD gummies now”, which isn’t super useful for intelligence. So the information in DNA isn’t that far off.

It’s not just DNA

Evolution provides lots of other information beyond just what’s written down in the DNA. And I’m not just talking about epigenetics—I mean all the information embodied in the physical structure of cells.

(I can feel everyone squinting right now.)

DNA is a “blueprint” for a cell. But information is needed to interpret that blueprint. Imagine a machine that could take in a DNA sequence and build a human cell. How many bits would be needed to describe that machine? A lot, right?

Of course, there’s a recursive “chicken and the egg” issue here: The machines that actually make human cells from DNA are… other human cells. But you need some information to get the loop started!

Here’s an analogy for programmers: Say I invent a new programming language called Dynoscript. (“Strongly typed immutable arrays and existential angst.”) And then I write a Dynoscript compiler in Dynoscript. Can I now run programs written in Dynoscript? No, because I have no way of running the compiler.

Where in DNA does it say that DNA is supposed to have a double-helix structure? Where does it say that “A” means C⁵H⁵N⁵? That information is represented in the physical configuration of the atoms in the cell, and is physically propagated when cells divide. (I’m sure there are better examples, but biologists get very stressed when pressured to think this way.) I have no idea how to quantify the amount of “embodied information” like this, but I’m sure it’s substantial.

But if you still think DNA is too small and you don’t believe in embodied information, that’s fine, because…

“Learning” is just one execution of the inner-loop

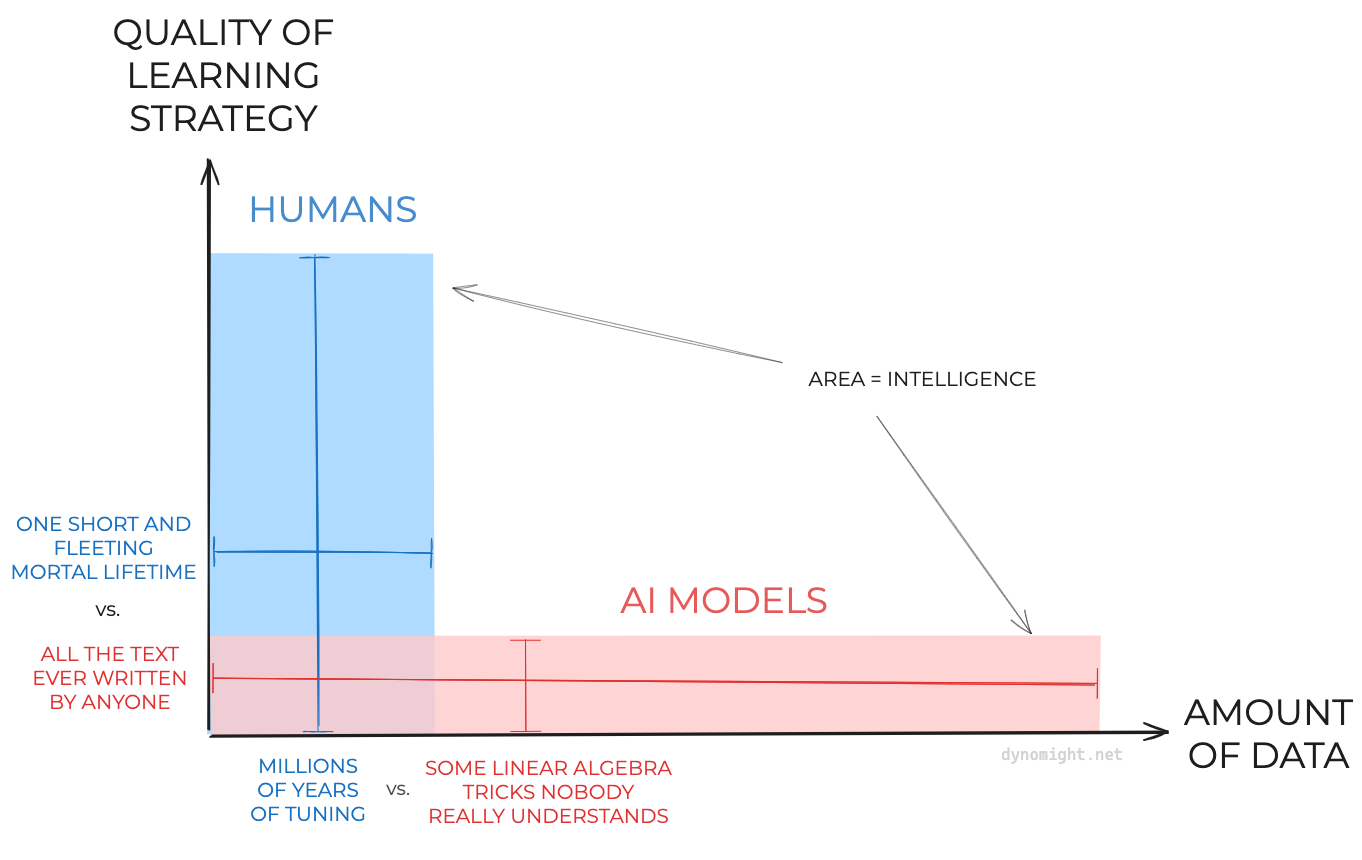

Here’s a cartoon showing how I think about the different contributions to human and artificial intelligence:

All of my test readers said that cartoon was confusing and futilely begged me to delete it. So probably I should explain.

We have been optimized by evolution. Partly evolution tuned our base instincts, like “food good” or “hypothermia bad”. But it also tuned the algorithm that we use to learn from our life experiences.

Human intelligence is the product of a “double-loop” optimization. In the outer loop, evolution tinkers with different learning strategies. In the inner loop, we are born as babies, we grow into adults following the strategy evolution gave us, we reproduce (or not) and we die. Then evolution picks the strategies that led to more offspring and uses them as the basis for further tinkering.

AI models are the product of a double-loop optimization, too. In the outer loop, human engineers tinker with different machine learning tricks. In the inner loop those algorithms are loaded into a giant cluster and run against data. The engineers pick out the strategies that work and repeat.

The most salient difference between these is who is in charge of the outer loop. But don’t get distracted by that.

The most important difference between these is that the evolution outer loop has executed many, many more times.

Also important is that each iteration of the evolution outer loop runs on “fresh data”. Imagine that GPUs became billions of times cheaper, and you hired billions of engineers so you could test billions of machine learning tricks in parallel. Problem solved? Not necessarily, because you’ll eventually “overfit” to whatever data you hold out to test generalization. There’s only so much you can squeeze out of a finite dataset.

Each bit from evolution integrates experience from millions of years of life and so may have a “multiplicative” effect on how effective in-lifetime learning is.

The human learning strategy might be vast and inscrutable

Even though it comes from evolution, humans are still using some learning algorithm. Just by definition, isn’t it possible to build an AI using the same tricks?

In principle, yes! But it might be very hard in practice. The key question is to what degree the human learning strategy “makes sense”. If it’s something simple, then probably we’ll eventually copy it. If it’s a collection of millions of unintelligible interacting “hacks” tuned to statistical properties of the environment, then maybe not.

Just because humans learn efficiently doesn’t necessarily mean their strategy will be easy to copy.

Caution on these cautions

Now hear me. I am not arguing that we will hit a data wall. Just because humans don’t need to pre-train on visual data doesn’t mean that visual data won’t be useful for AI. And just because human learning strategies integrate vast amounts of information from our evolutionary history doesn’t mean that algorithmic progress is impossible. I’m just saying that if you want to argue for visual data or algorithmic progress, a direct argument is more convincing than gesturing at some human babies.

P.S. I’ve been feeling grumpy about algorithms deciding what we read, so I’ve decided to experiment with links to writing that I think deserves more attention. Today’s link is to Philosophical Multicore on Outlive: A Critical Review.

Well joke’s on you, I already exercised today, and now I’m back to over-analyze saturated fat. My assessment:

Saturated fat is unhealthy in expectation: likely true (credence: 85%).

It’s a good idea for most people to reduce their SFA intake: possible (credence: 50%).

It’s a good idea for people with high cholesterol to reduce their SFA intake: likely true (credence: 70%).

The data are unclear: unclear. (Yes, it’s unclear whether the data are unclear. It depends on how much clarity you want.)

In the same spirit, if you’ve written a blogpost-sized response to this—or any—post let me know and I’ll strongly consider sending it out at the bottom of a future post. (Unless it’s really bad, in which case I won’t.) And in the spirit of that spirit, if you liked this post, consider sending it to a friend.

Thanks for writing this. It seems obvious to me that evolution accounts for 95+% of human learning and 100% of human intelligence. A better way to think of it is how many bits is needed to store the algorithm for learning and/or intelligence, and I think the answer is that it's probably pretty low. The problem is finding it, which clearly takes enormous optimization pressure and large amounts of data and computation, which is what evolution has been doing for the past billion years.

Another way to phrase the same thing is to consider the size of current models. Clearly most of those parameter values are spent storing very impressive amounts of encyclopedic knowledge that no human comes close to matching. I'm confident the parameters of a future very intelligent model without as much world knowledge can fit on a thumb drive, but actually getting to that specific set of descriptive bits will require a fire hose of data and computation, just as evolution has needed.

Adding to your point, evolution isn't "survival of the smartest/strongest", it's the survival of the organisms that are most adaptable to a changing environment. The reason we're the dominant organism isn't just that we have big brains, it's that those brains make us extremely adaptable and let us squeeze all the utility we can out of anything. If we watch someone start a fire, we learn how to start a fire.

Also, I would add an intermediate loop - society "evolves" exponentially and even faster than evolution, which lets us gain from things we don't directly experience. Compare the way information is retained across species:

An ant colony: ants can go outside and leave temporary chemicals.

An ape troop: if one ape learns something, it can inform the others, but information will be lost if it's not important enough to remember.

A human: I can read things written centuries ago. (Graffiti written in Pompeii nearly 2000 years ago tells us that Gaius and Aulus were friends.) If I don't understand something I read, I can read something else, and eventually I'll understand it.

In other words, we can retain information over time, and evolution has programmed us to squeeze all the juice we can out of the information we gather. In contrast, LLMs learn very inefficiently. They struggled with math at first because having verbal descriptions of algorithms doesn't mean it can use those algorithms. (They have gotten better, but I don't know whether that's because they know to call a separate tool to crunch the numbers or not.)