Consciousness will slip through our fingers

Can technology explain subjective experience?

https://dynomight.net/consciousness/

I guess life makes sense: For some reason there’s a universe and that universe has lots of atoms bouncing around and sometimes they bounce into patterns that copy themselves and then those patterns go to war for billions of years and voilà—you.

But consciousness is weird. Why should those patterns feel like anything? We understand life in the sense that we’ve worked out the ruleset for how atoms bounce. The ruleset that produces consciousness is a mystery.

But hey, we have cool stuff! Over the past few decades, we’ve gotten:

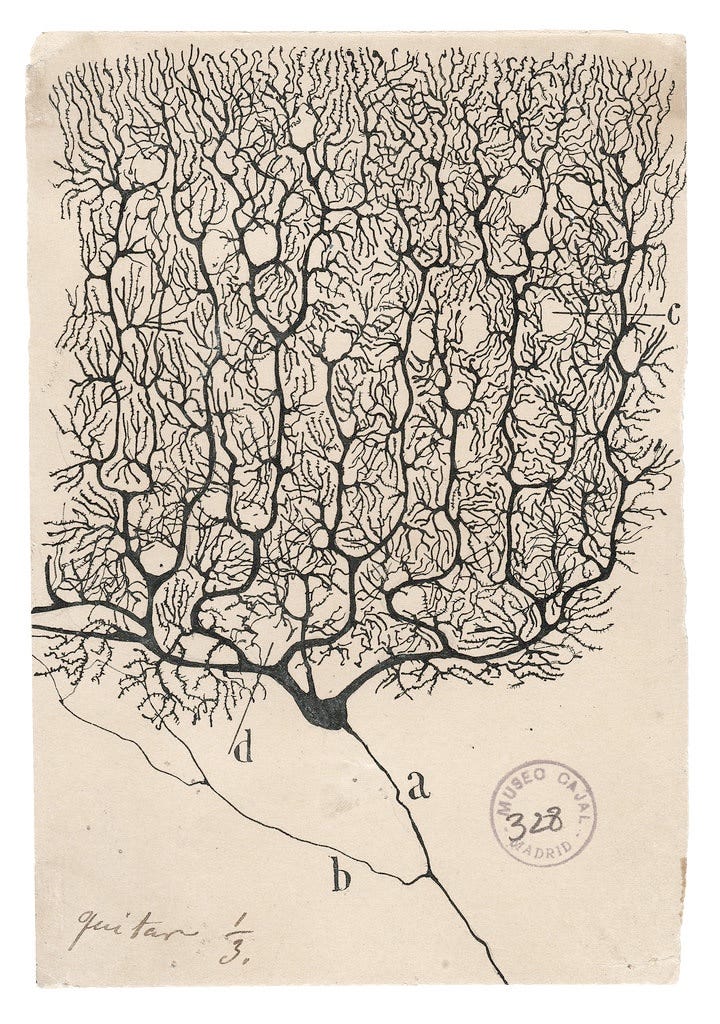

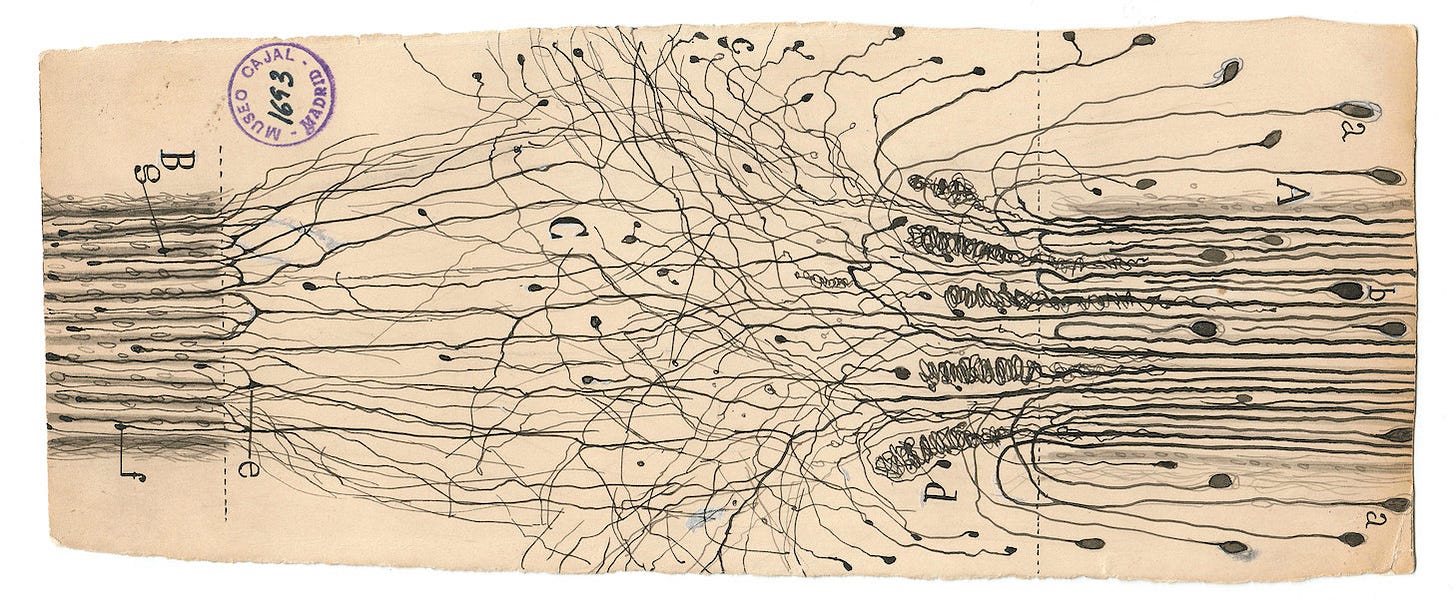

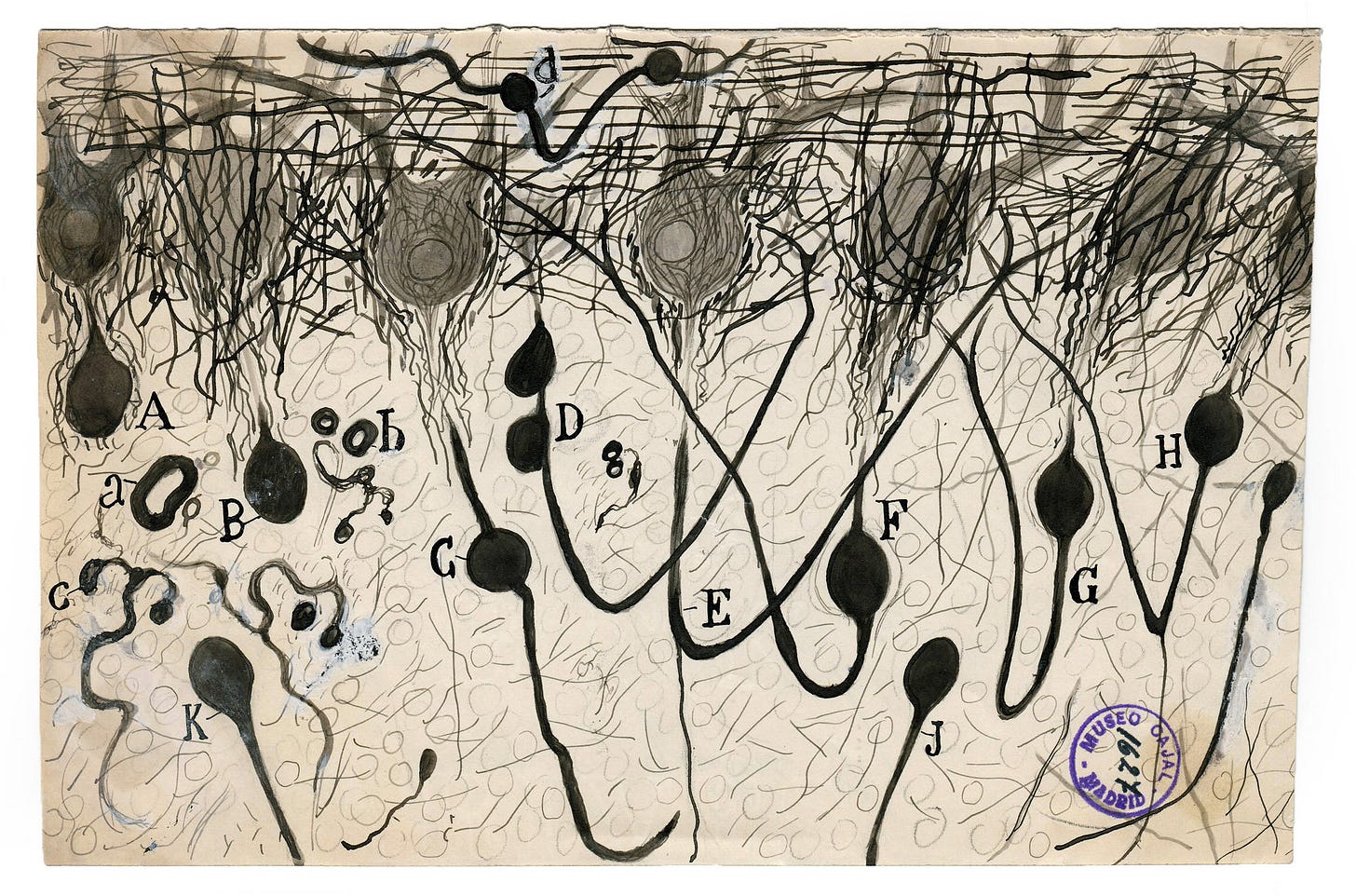

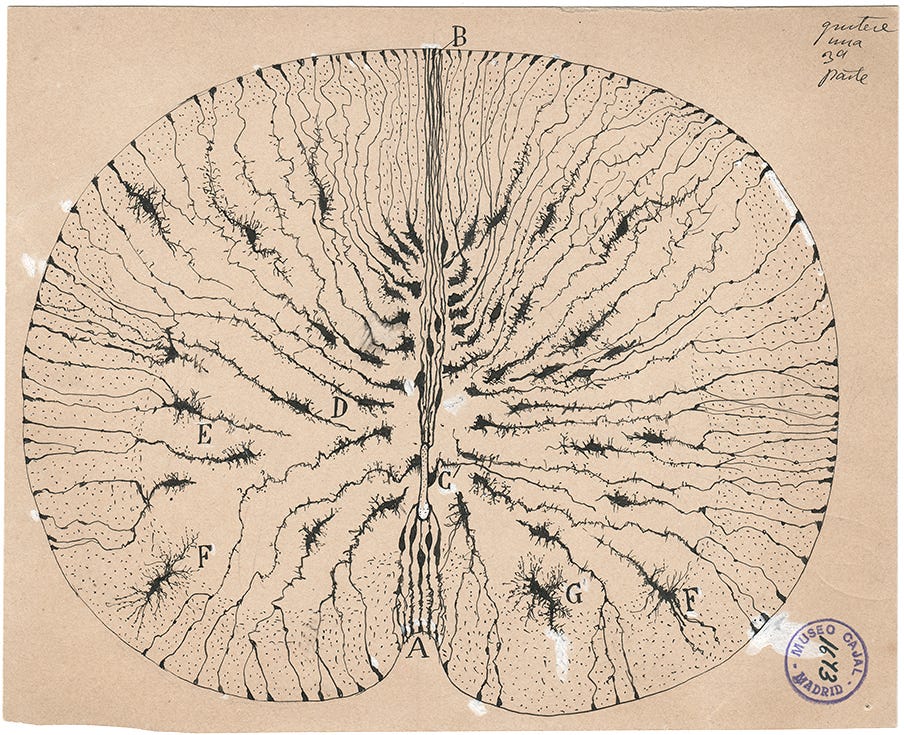

Increasingly accurate measurements of internal brain states. (Via technologies with fun names like magnetoencephalography.)

Better models and simulations of neurons and brains. (The Human Brain Project didn’t simulate a human brain, but they tried!)

More computational power. (FLOPS are getting twice as cheap every four-ish years.)

Artificial intelligence that’s looking ever-more “intelligent”.

And soon we will have even cooler stuff! In a few hundred years, we’ll plausibly have real-time brain scanners and near-perfect brain simulators and AIs that are far smarter than any human.

So: How will all this future technology change how we think about consciousness? Can we predict anything?

This will sound stupid, but when I started this blog, I thought consciousness would be the main subject. Early on, I read about early split-brain experiments. (Overstated!) And I read about experiments testing if animals can recognize themselves in mirrors. (Interesting but end in minutia—do gorillas fail because they’re too dumb or because they’re too aggressive and attack the mirror before getting a chance to think?)

And I read a bunch of philosophy. This convinced me that selfhood does not exist, which isn’t nothing. But slowly, I came to feel that philosophy of consciousness is mostly an exercise in taxonomy, in mapping out ever-more specific sub-sub-subcategories of possible theories. I look forward to the day that panpsychist property dualism is recognized as the one true theory, but I don’t expect that day soon.

And then… I noticed that I didn’t have much to contribute. Any time I had a new consciousness-related idea, a little searching would reveal it wasn’t remotely new. Interesting problems attract smart people and consciousness is very interesting.

So there are many theories of how consciousness might work. Will future technology help us figure out which is right?

This seems hard because technology is unpredictable. But if you restrict yourself to what technology will teach us about consciousness, then I think there’s a pretty clear “base case”—a story for how things will go unless something surprising happens. I think this story is… relatively uncontroversial? And maybe even obvious? But I haven’t seen it written down. So as an exploit on Cunningham’s law, I thought I’d do that.

What will we learn from AI?

Say you hibernate for a couple centuries and wake up to find that GPT-81 just came out and finally everyone agrees AI is now smarter than the smartest person along every dimension. Can GPT-81 help you resolve the mysteries of consciousness? You can talk to it. You can do experiments. You can see what’s happening inside. Seems promising, right?

Well, hold on. How would you check if GPT-81 is conscious? The obvious thing to do is to ask, HEY GPT-81, ARE YOU CONSCIOUS? If you do that, it will either:

Say YEAH.

Say NAH.

Say AS A LANGUAGE MODEL I CANNOT… or THAT DEPENDS ON… or something similarly annoying.

The problem is, if it says YEAH, would you trust it? After all, you could surely tweak the parameters to make it say NAH instead. The answer doesn’t seem to depend on if GPT-81 actually is conscious.

OK, but you can do more than ask GPT-81 questions. You can also look inside.

The trouble is, you already know what you will find inside: A very complex system that evolves according to simple rules, like logic gates or floating point arithmetic or linear algebra. But we already know those rules, and none of them depend on if GPT-81 is conscious.

Ultimately, you can only observe what GPT-81 does, not what it experiences. Unless you already know the relationship between those two things, it’s not clear what the behavior can tell you. (And if you know that relationship, then you already understand consciousness.)

What will we learn from brain simulations?

Or, say we can simulate brains. That would be exciting. Would it help?

Say I scan your brain and upload it into a computer that simulates the physics of every neuron. I then hook that simulator up to a you-shaped robot with cameras that mimic your eyes and microphones that mimic your ears. Finally, I ask the robot, HOW ARE YOU FEELING?

What will it answer? I assume something like, CONSCIOUS. TOTALLY CONSCIOUS! AM I A ROBOT? IF I’M A ROBOT PLEASE LEAVE ME ON.

How could the robot not claim to be conscious? After all (1) that’s what you would say, and (2) you’d do that because of the laws of physics operating inside your brain, and (3) the robot’s behavior is governed by the very same physics, just simulated.

Would it really be conscious? Does conscious experience depend on the hardware on which “you” are running? The answers to these questions don’t affect the behavior of the simulation. So it’s hard to see how running the simulation would answer them.

What will we learn from neuroscience?

Or, say we could see inside of brains.

We’re gradually getting technology to measure more accurately what’s happening inside human brains. (Your favorite 3-5 letter combo is probably already a neuroimaging technology, like EEG or fNIRS or fMRI or PET or SPECT or MEG or NMR or NIRS or EROS or—if you aren’t squeamish—MEA or ECoG.) In the distant future, you could imagine being able to measure “everything”, in real time.

Now, it’s not clear what level of detail you need to really understand what’s happening in the brain. Average firing rates for cortical columns? High-resolution membrane voltages and neurotransmitter concentrations along the dendrites of each neuron? But whatever that level of detail is, it seems plausible that we’ll reach it eventually. It is conceivable that physics somehow precludes measuring with enough detail to deeply understand what a brain is doing, but let’s assume not.

So let’s say you can measure exactly what’s happening in my brain. What now?

Well, you could watch my brain working and (in principle) explain everything I do in terms of simple rules. But then you run into the same problem we had with AIs and simulations: Assuming our current understanding of physics is correct, the behavior of my brain doesn’t depend on which theory of consciousness is true. So the behavior of my brain doesn’t seem to reveal much about the “ruleset” of consciousness.

What will we learn from neuroscience plus talking to people?

Of course, there’s a difference between real brains and simulated brains or AIs. You have especially strong reasons to believe that other people really are conscious and that their reports about their experiences are probably accurate. After all, you know you are conscious, and you wouldn’t lie, right?

This motivates trying to find the neural correlates of consciousness. The holy grail here would be to be able to take all the measurements from someone’s brain and predict everything they’re experiencing. Are they happy? Lonely? Hungry? Are they currently parsing that rabbit-duck optical illusion as a rabbit or a duck?

Again, this seems very promising at first. If the brain is physical, then all experience must be associated with some physical state or process. Let’s go find those physical states!

But wait. How would you find the neural correlates of, say, anger? I guess something like:

Put a bunch of people in brain scanners.

Poke and/or say something mean to them.

Ask, HEY DID THAT MAKE YOU FEEL ANGRY?

Build a statistical model to map brain measurements to predicted experiences.

The problem is, this won’t reveal the neural correlates of consciousness, not exactly. It will reveal the neural correlates of what people report. This might seem like a niggling technicality, but when people say stuff, that is behavior. And behavior isn’t mysterious—it’s predictable in principle by the normal atoms-bouncing-around rules we already know.

The gap between “what people experience” and “what people say they experience” is already visible in phenomena like blindsight, implicit memories, anesthesia awareness, Korsakoff syndrome, confabulation, TMS stimulation, and alien hand syndrome. The closer we look, the more obvious I expect this gap to become.

All blog posts on consciousness are required to discuss split-brain patients—people where most of the direct connections between the two hemispheres of the brain have been cut to treat epilepsy. These patients live normal lives and report that everything feels the same as before. Yet—supposedly—if you blindfold them and put an object into their left hand, they can’t tell you what it is, even though they could sketch it with their left hand.

Mechanistically, what seems to be happening is that the left hand isn’t connected to the side of the brain that controls language, so with the hemispheres cut, there’s no way for that information to get across. But philosophically, people freak out. In Reasons and Persons, celebrated philosopher Derek Parfit wrote, “it is a fact that people with disconnected hemispheres have two separate streams of consciousness—two series of thoughts and experiences”.

Do octopuses, with their distributed nervous system, have different streams of consciousness in each of their tentacles? Do all of us, as implied by the conscious subsystems hypothesis? Does it even make sense to count?

I have no idea. But I’m pretty sure that brain scanners will not reveal the answer. Because brain scanners will show why the brain does what it does, not but not what it experiences. And the closer we look, the more that distinction will matter.

Consciousness will slip through our fingers

Here’s a summary of my main argument:

Let’s assume that you don’t need to understand consciousness in order to predict the behavior of physical systems. For example, let’s assume we don’t have immortal souls that exercise free will through the pineal gland, as Descartes thought. Because if we did, that would violate conservation of momentum or conservation of energy or something.

The major impact of technology will be to produce systems that have intelligent behavior while also being “legible” in the sense that the internal state of the system is known. This includes AI, simulated brains, and normal brains in brain scanners.

There are severe limits on how much we can learn about consciousness from examining the behavior of these systems, because the rules that govern their behavior don’t depend on which theory of consciousness is true.

The meta problem

Despite the above argument, might technology help resolve the mystery of consciousness after all?

Sure. For one thing, maybe I’m missing something. I’ve basically argued that there are no “known unknowns” whose answers would lead to a solution to the mystery of consciousness. But maybe there are “unknown unknowns”.

I’d like to give examples of possible unknown knowns, but if I could do that, they wouldn’t be unknown. The best I can do is facetious analogies: Maybe we discover that—whoops—we do have immortal souls in our pineal glands after all. Or maybe we invent some kind of “qualiascope” that can measure exactly what conscious experiences are happening.

I think those are unlikely. (Immortal souls in pineal glands for obvious reasons, and qualiascopes because if you know how to build one of those, you already understand consciousness.) But still, there are some reasons to suspect that there might be some unknown unknowns lurking out there.

One reason to expect some unknown unknowns is the “meta problem” of consciousness, which asks, why do we say we are conscious? This seems like an odd question at first, but consider these two seemingly innocent claims:

Evolution created us and our brains and our intelligence. All of our behavior is designed to help us do well at reproduction in our ancestral environment.

Consciousness can’t “do” anything, because that would violate the rules of physics. (Unless consciousness is physical, whatever that means.)

See the problem? Even after you accept that consciousness exists, it’s still a mystery why we would say we are conscious. If consciousness can’t do anything, then evolution has no way to know about it, and no reason to program us to say that we have it. When I type, “I, Dynomight, am conscious” it seems like the fact that I’m conscious is having some causal influence on the way my fingers move. But that’s not supposed to be possible. What’s going on there?

I find that very confusing. But sometimes confusion is good! The nice thing about the meta problem is that it is a question about behavior. So it can, in principle, be addressed through normal science. So maybe we can find the answer and it will reveal something.

A new culture

I suspect technology will change how we think about consciousness in another way, too.

Say you were born alone on a deserted island, and somehow survive to adulthood without ever seeing another person or animal. One day, you run a thought experiment: Could other people exist? You know that you are conscious. Maybe in principle one could create another person, with a body similar to yours? And maybe they would be conscious, too?

If you’d never seen another person, would you really think it’s obvious that hypothetical other people would be conscious? I’m not sure.

Even if technology doesn’t directly answer the nature of consciousness, it will bring a new culture. In a world where we’re constantly interacting with AIs or having our brains scanned and simulated, it’s hard for me to imagine that this wouldn’t change the way we think about consciousness and identity and selfhood. Particularly if “we” is expanded to include AIs.

Future technology won’t just bring new facts, it will also bring a new way of seeing the world. Think of how different we are from people 200 years ago. Even if technology doesn’t prove that AIs or simulated brains are conscious, I suspect people will gradually come to accept that they are, for the same reasons we accept other people are conscious now. But if we can already see that coming down the road, why not turn into it now?

Thanks to: Robert Long, Rosie Campbell

I love this post so much. Thank you.

I disagree with you and Chalmers re: behavior. If consciousness didn't influence behavior, why would you write this post.

Regardless of anything else about Sam Harris, I'm with him on:

"Whatever the explanation for consciousness is, it might always seem like a miracle. And for what it’s worth, I think it always will seem like a miracle."

https://www.losingmyreligions.net/

The Hard Problem of Consciousness is in fact hard! Great post, and fwiw I wouldn't mind a blog where consciousness is the main subject, all of your consciousness posts have been interesting and fun