Bourdieu's theory of taste: a grumbling abrégé

what the stuff we like says about us

I recently noticed that when I buy beer, I sometimes get Belgian Trappist Quintupel. And I sometimes get American Fermented Value Product. But never Blue Moon or Sam Adams or Peroni or Becks or Pilsner Urquell.

Why? I guess I thought I did that because I was… quirky and free-spirited? Unlike people who buy stuff based on marketing, I was independent and multifaceted.

But then I noticed it’s not just beer:

And isn’t it odd that things coded as highbrow or lowbrow are always OK, but never middlebrow? And is that really a coincidence?

Or maybe—just maybe—are my beer purchases a clue that underneath it all I’m a striving, pretentious, hypocritical, sniveling excuse for a human being?

I was led to these reflections by Pierre Bourdieu’s 1979 book, Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. It’s full of inviting 176-word sentences like this:

Again, to understand the class distribution of the various sports, one would have to take account of the representation which, in terms of their specific schemes of perception and appreciation, the different classes have of the costs (economic, cultural and ‘physical’) and benefits attached to the different sports—immediate or deferred ‘physical’ benefits (health, beauty, strength, whether visible, through ‘body-building’ or invisible through ‘keep-fit’ exercises), economic and social benefits (upward mobility etc.), immediate or deferred symbolic benefits linked to the distributional or positional value of each of the sports considered (i.e., all that each of them receives from its greater or lesser rarity, and its more or less clear association with a class, with boxing, football, rugby or body-building evoking the working classes, tennis and skiing the bourgeoisie and golf the upper bourgeoisie), gains in distinction accruing from the effects on the body itself (e.g., slimness, sun-tan, muscles obviously or discreetly visible etc.) or from the access to highly selective groups which some of these sports give (golf, polo etc.).

But sociologists insist it’s one of the greatest works of the 20th century. So I figured—what the hell—why not fight through 600 tangled pages? Does it say something interesting? Is it written like this for a reason? Will I learn to like this kind of writing and thereby gain some sort of enlightenment?

(Because it’s hard. Yes. Yes, but it’s bad. No.)

On Bourdieu

Bourdieu had a unique life history and personality. And I really want to tell you about them, because they paint a sympathetic picture. But I’m sure Bourdieu would hate the idea, so I’ll defer them to later. As a little hint, here’s the first page of his autobiography:

On his theory and my revenge

I’m worried that the above quote doesn’t convey how hard Distinction is to read. Yes, it’s long. Yes, it uses outsider-art sentence structure. But it’s not just a dense jungle—it’s a dense jungle inside a labyrinth.

As soon as the book starts, Bourdieu takes off and launches into all his ideas, all at once. He invents new terms without giving clear definitions and also redefines normal words without first alerting you that he’s done that. Even when things seem clear, his flailing organization means critical caveats might show up in the middle of a paragraph 90 pages later. And did I mention that the sentences are hilariously long and branching and ponderous?

In the preface to the English translation, Bourdieu hints at a justification:

Likewise, the style of the book, whose long, complex sentences may offend—constructed as they are with a view to reconstituting the complexity of the social world in a language capable of holding together the most diverse things while setting them in rigorous perspective—stems partly from the endeavour to mobilize all the resources of the traditional modes of expression, literary, philosophical or scientific, so as to say things that were de facto or de jure excluded from them, and to prevent the reading from slipping back into the simplicities of the smart essay or the political polemic.

(Does the fact that French readers got no such justification imply more respect, or less?)

I find Bourdieu personally appealing, and I think this book has important ideas. Still, here’s how I read that quote:

“My ideas are too complex to be contained in normal human language.”

“By being obscure, I can force everyone to take me more seriously.”

I don’t buy it. Mostly I feel the writing style just forced me to waste a huge amount of mental effort decoding everything. So, feeling vengeful, I decided to distill the basic idea of the book (as I understand it) into the ultimate un-Bourdieu style: A linear argument in seven parts, based on comics.

Claim 1: Class predicts taste.

Rich educated people like different stuff than poor uneducated people. That includes food, books, clothes, movies, TV, cars, hobbies, music, etc.

(Synthwave is a genre of electronic music.)

Bourdieu gives lots of evidence for this for France in the 1960s. But I’m sure it’s also true across the Anglosphere in the 2020s. And it’s not just access. People from different classes prefer different stuff. Isn’t that weird? What explains it?

Claim 2: Taste predicts class.

If I like hunting and country music and country-fried steak, that tells you something about me. If I like yoga and anti-folk and vegan-thai-ethiopian-fusion, that tells you something else.

This is uncomfortable because class is uncomfortable. Sure, anyone can like whatever they want. But let’s not kid ourselves—statistically, knowing someone’s tastes tells you a lot.

This claim follows from the first one by basic probability. Bourdieu argues for it with poetic and (pseudo?) profound statements like, “Tastes classifies, and it classifies the classifier.”

Claim 3: Appearing to have certain tastes—and thus to be part of a given class—has important consequences.

It’s human nature to favor people who are similar to us. It’s easier to feel comfortable with them, to understand them, and to trust them. If you’re interviewing them for a job, you’ll more easily feel they’re a good “cultural fit”.

We also tend to socialize with similar people who are “into” similar stuff as us. And lots of opportunities depend on having the right social connections.

But the jobs and social circles that lead to the upper class are filled with… upper-class people. Who like upper-class stuff.

Claim 4: We respond to those incentives.

We know this is happening, and we adapt.

Claim 5: Mostly, we respond to those incentives unconsciously.

Bourdieu doesn’t claim we’re sitting around deliberately calculating what we should like. It’s more that some hidden part of your brain infers that liking (or disliking) something will benefit you. And then you find that you actually start liking (or disliking) it. So the previous cartoon should look more like this:

Claim 6: But having the “right” tastes is not easy.

Ever had a conversation like this?

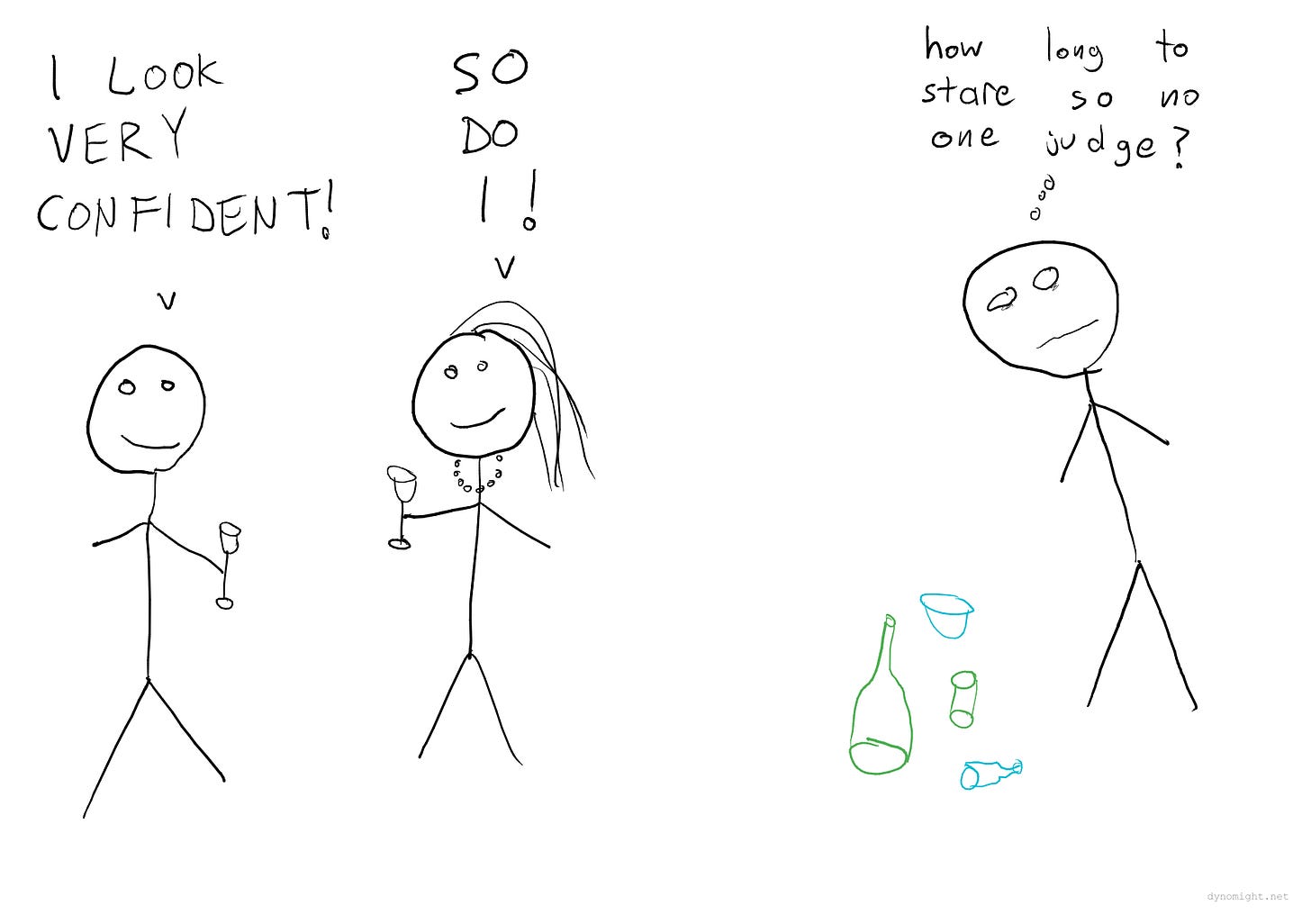

A few months ago, I went to an art opening. The art was a bunch of glass bottles arranged on the floor. At the time, I didn’t think about it much. But now—because Bourdieu—I wonder what that scene looks like to a newcomer. Is it like this?

Or maybe this?

If you go see some classical music, no one tells you you’re supposed to sit completely still during the music and never clap between movements. If you go to a Thai restaurant, they might provide chopsticks, but they don’t tell you you aren’t supposed to use them. If you go to a rave, no one tells you that it’s been 20 years since anyone called them “raves”. And how much knowledge is needed to appreciate cricket or American football or—god help you—Australian rules football?

If you’re an outsider and anyone is paying attention, they will notice. The only way to look like you belong is to actually belong.

Claim 7: So taste helps class entrench itself.

Maybe our lives have a path dependency. Some people get early access to upper-class culture. This kicks off a feedback loop where they learn to like that culture more, are more accepted upper-class social circles, get more knowledge and “better” taste, and eventually get economic opportunities (like jobs) and social opportunities (like marrying high-class people).

People who don’t get that early access aren’t accepted in those circles, can’t develop their tastes, and fall behind. Early exposure means some people are pulled up into the upper class and others are pushed down.

So why don’t lower class people just switch to the right tastes? Well, some try! But it’s hard to do it if you’re not “in” that world. You’ll make “mistakes” and give yourself away.

And at the same time, lower-class people are in a sort of local maxima, where they get more benefits from having other tastes. If you live in a rural area, hunting and Nascar probably pay higher dividends than polo and opera.

And, of course, we mostly just do stuff we actually enjoy. Evolution didn’t give us instincts to adopt weird tastes no one we know cares about, just so we can impress some upper-class jerks whose culture seems almost designed to be impenetrable.

On legitimate culture

In Bourdieu’s telling, a major character is “legitimate” culture. This is stuff like Bach or opera or avant-garde theater or Nabokov or Shelly or golf or skiing or playing the violin or fancy food on tiny plates—basically what a cliche rich snob would like in a cartoon.

He tells a story where schools imply to students that these things are “truly” better. But upper-class students already had some exposure at home, so they do better in school and feel like they “belong” in the existing system, while lower-class people are subtly pushed out. Eventually those upper-class students take over museums and universities and decide what good taste is for the next generation.

I’m not sure how well this story generalizes from 1960s France to the Anglosphere today. It surely does to some degree. But I feel like upper-class people today just… don’t care that much about “legitimate” culture? And I don’t think institutions are so important in determining what high-class tastes are.

I’m sure some rich kids like opera. But I still think the social hierarchy on the playground is more determined by who wears the right t-shirts and listens to the right pop music than by familiarity with Puccini.

On legitimate language

While I’m skeptical of that story about “legitimate” culture today, it’s interesting to think about the analogy to language. Some people grow up speaking dialects of English that are associated with the working class, e.g. Black English in the US or Cockney English in the UK. Of course, these dialects are internally consistent and no better or worse than “standard” English. Yet schools say or imply that these dialects are “incorrect”. This surely produces similar dynamics.

Bourdieu doesn't seem to point out this analogy in the book, despite that he himself grew up speaking a Gascon dialect.

(As an aside, should schools encourage students to use “standard” English? Maybe not, since it’s unfair for society to reward people for growing up in higher-class homes. Or maybe so, since—unfair or not—if that’s the reality, it benefits the individual student to adapt to it.)

On abstraction and omnivores

Bourdieu has a unifying theory for what upper-class taste is about: It’s a taste for the abstract, for appreciating the pure form. Upper-class people like abstract paintings and breaking the 4th wall in theater and weird food presented on rocks, because my what an interesting thing you did there with paint/actors/ingredients. Lower-class people like pretty landscapes and nice stories with good characters and hearty filling food.

In one of his surveys, he asked if photographs of various subjects would more likely give a photo that is ugly, meaningless, interesting, or beautiful. Less-educated people thought a first communion would be beautiful and the bark of a tree would be meaningless. Highly-educated people thought the opposite.

But in a couple places, Bourdieu notices hints of a different trend:

Thus, in the dominant class, the proportion who declare that a sunset can make a beautiful photo is greatest at the lowest educational level, declines at intermediate levels […] and grows strongly again among those who have completed several years of higher education and who tend to consider that anything is suitable for beautiful photography.

In the 1990s, sociologists suggested a different theory: High class people are cultural omnivores: The true upper-class person likes all kinds of food and all types of movies and books and likes traveling to all countries and likes all kinds of hobbies.

This is certainly what I see today. Up until the early 2010s, I’d often hear people say, “I like all kinds of music except for [subset of rap, heavy metal, country].” Today, that would be passé. If you ask people what kind of music they like, they often don’t want to name any genres, and if you force them, they’ll insist on naming ten.

Of course, that doesn’t mean Bourdieu was wrong. Probably things just changed. Why? Well, one conspiracy theory is that it just became too easy for lower-class people to imitate upper-class tastes, so upper-class people moved to higher ground.

On sympathy

Today, it’s common to see the world described as essentially a pure hellscape of oppression, an endless plane of boots micro-aggressing onto human faces—for ever.

I’ll just admit—to me, the everyone-is-oppressed-by-everyone-else discourse sometimes seems a bit unhinged. So I was amazed how much more compelling I found this kind of argument when it was coming from Bourdieu. I think that’s because he’s railing against a mainstream where such ideas basically didn’t exist. Partly this helps by forcing him to argue from first principles. But also, I think it’s more convincing because it’s hard not to cheer for the little guy fighting the good fight against the blind injustice of the existing status quo.

So that’s one reason to go back and read Bourdieu himself: The neutered version of his ideas that comes out of HR / DEI / PR departments today just doesn’t have the same charm.

Much more on Bourdieu coming soon (please don’t unsubscribe).

Man whenever I see reviews of these older critiques on class vis a vis "taste" I always feel insane that nobody ever seems to think "people with more money can do more things and have more options and so will naturally have different preferences, guy with 40 choices is gonna have different preferences from guy with 5 choices" and was ready to despair again here until we got to the omnivore part which at least gets most of the way there.

"Thus, in the dominant class, the proportion who declare that a sunset can make a beautiful photo is greatest at the lowest educational level, declines at intermediate levels […] and grows strongly again among those who have completed several years of higher education and who tend to consider that anything is suitable for beautiful photography."

In short: the midwit meme rules supreme.