A review of early split-brain animal experiments

What happens if you cut your brain in half?

Note: Your feeble email client may refuse to display this post in its full length. If so — and you somehow make it that far — you can read the whole thing at dynomight.net/split-brain/.

What happens if you cut your cortex in half? When this was first tried on animals, the answer amazingly seemed to be not much. But starting in the late 1950s, a series of split-brain experiments found that very weird things happen under careful testing. This was done first in cats, then monkeys, and eventually humans.

These experiments are fascinating for their implications into the mind, consciousness, and selfhood. However, existing presentations of these experiments tend to have a strong interpretive narrative. When I went back and actually read the original papers, I concluded these narratives are dangerous. It’s way too easy to explain away inconvenient results everywhere to tell whatever story you want.

These experiments are just so weird, and their implications so fascinating, that the only way to make sure you’re getting an accurate picture is to focus on the facts: What was actually done, and what was observed?

Here I’ll review early animal experiments, particularly those that set the stage for Roger Sperry’s later research on humans.

A Reminder About Mammal Brains

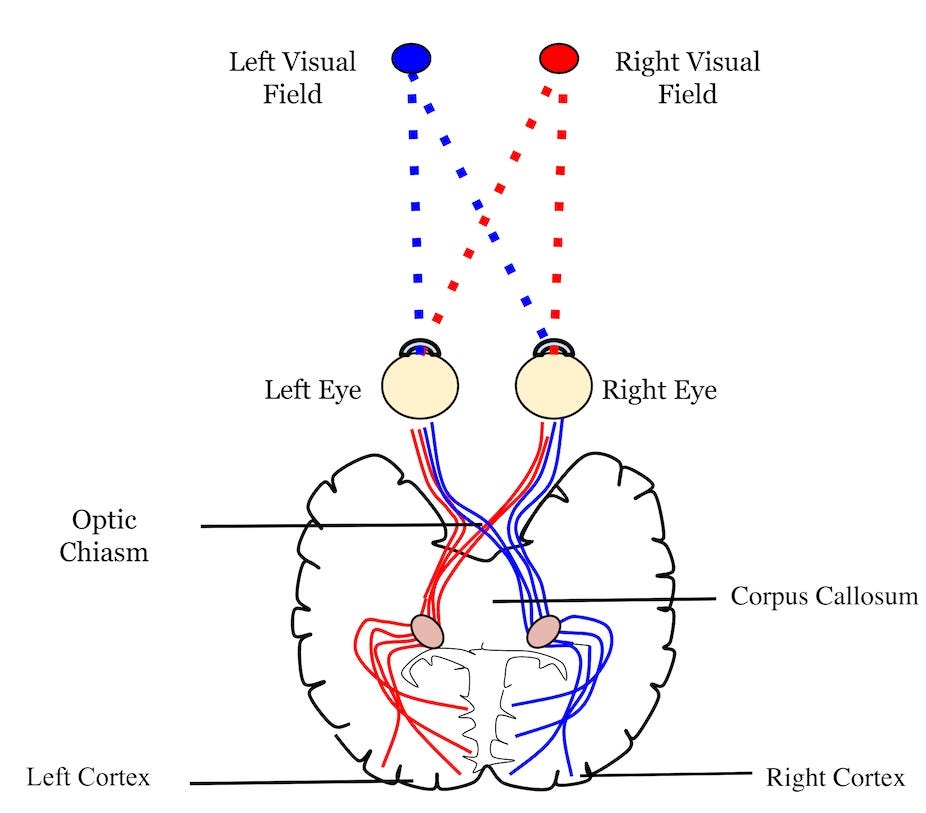

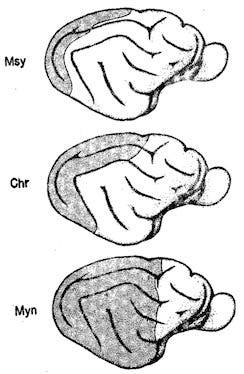

The outer layer of the brain is the cortex, key for attention, perception, memory, vision, and language. The cortex has two hemispheres which communicate mainly via the corpus callosum. They also communicate via the subcortical brain and indirectly through the body.

Light from both eyes first goes to the optic chiasm. This relays the signal from the left side of both eyes to one hemisphere of the cortex, and the signal from the right side of both eyes to the other hemisphere.

It appears that one side of the body is primarily but not completely controlled by one half of the cortex.

Myers 1955

Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 1955

WHAT THEY WANTED TO TEST. Say you do surgery so one half of the brain only gets visual information from one eye. Then, you train cats to do some task using only one eye. Will they also be able to do it using the other eye, which never got any direct visual information about the task?

WHAT THEY DID. They took 9 cats, and cut the optic chiasm, so that light from one eye now only goes to one half of the cortex. They then covered one eye with a patch, and put two doors in front of the cat with different shapes on them, e.g., a square and a circle. One shape always led to food, the other to an electric buzzer.

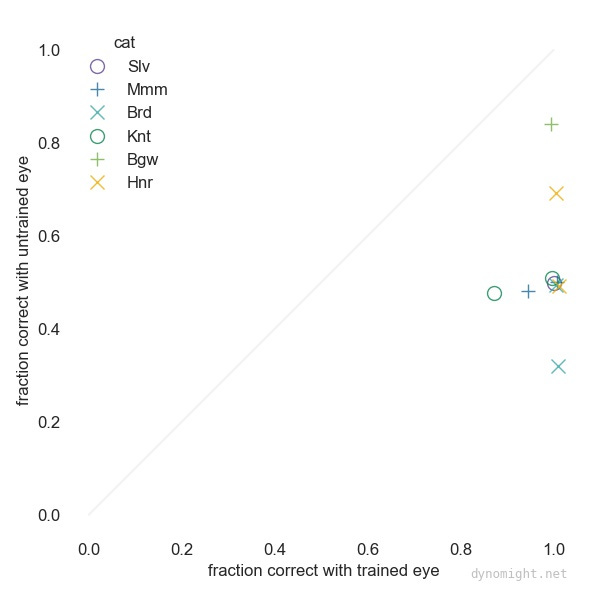

Every day, they repeated trials with the positions of the doors chosen randomly day until the cat was no longer hungry and stopped cooperating. They kept this up until the cat could get 34/40 trials correct, and then just did 40 trials per day for a while. Finally, they switched the patch to the other eye and tested how well the cat did. They repeated the whole process with different shapes.

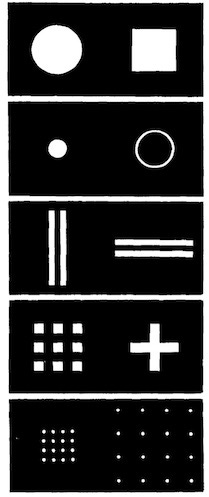

WHAT THEY FOUND. Here’s the fraction of trials the cats got correct in the last few training sessions (on the x-axis) and the testing session (on the y-axis). Each marker shows one cat (named “Mmm”, “Bbw”, etc.) on one pattern. The same marker is repeated if the same cat was tested on multiple patterns.

The cats did somewhat better with the trained eye, but they did pretty well with the untrained eye, too.

Myers 1956

WHAT THEY WANTED TO TEST. What if you did the previous experiment, except instead of just cutting the optic chiasm, you also cut the corpus callosum?

WHAT THEY DID. The previous experiment, except instead of just cutting the optic chiasm, they also cut the corpus callosum.

WHAT THEY FOUND First off, the cats were fine, with no obvious problems in coordination or anything else. (This is probably the most surprising result of all!) As for performance, the untrained eye did much worse than the trained eye, usually only getting 50% correct, the same as random guessing.

In two cases (Bgw and Hnr) the cats did generalize OK. Myers claims these aren't "true exceptions", though I'm a bit skeptical.

Sperry 1956

Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 1956

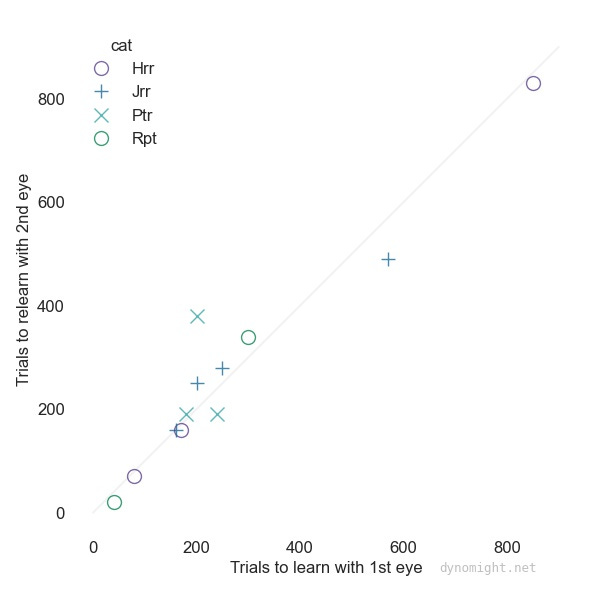

WHAT THEY WANTED TO TEST. Say you again cut the optic chiasm and corpus callosum. We saw above that they usually do poorly with the test eye. But can they at least re-learn the pattern with the test eye faster? This would suggest that some information is still getting between the two halves of the cortex.

WHAT THEY DID. They took 4 cats and again cut the optic chiasm and the corpus collosum. They trained one eye of the cats to recognize the pattern, doing trials of 10 and stopping when a success condition was reached, meaning the cat was doing well. They then trained the other eye, and compared how long it took to reach the same condition.

WHAT THEY FOUND. There’s not much speedup with the second eye. (They didn’t verify that there was a speedup with an intact corpus callosum, presumably because Myers 1955 already did that.)

Stamm 1957

Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 1957

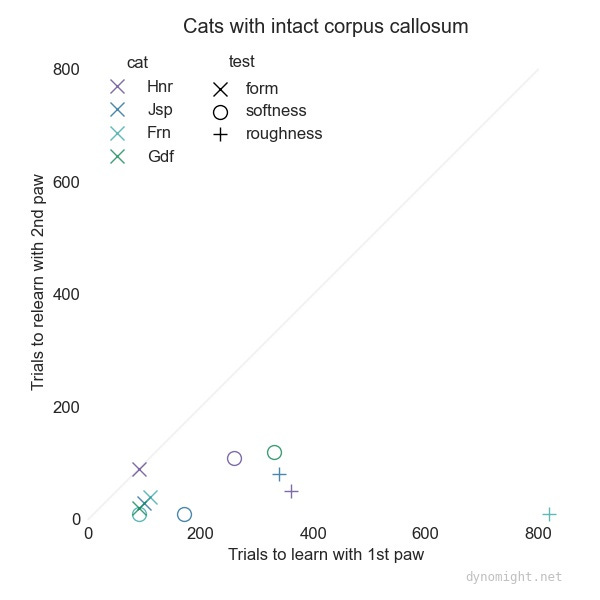

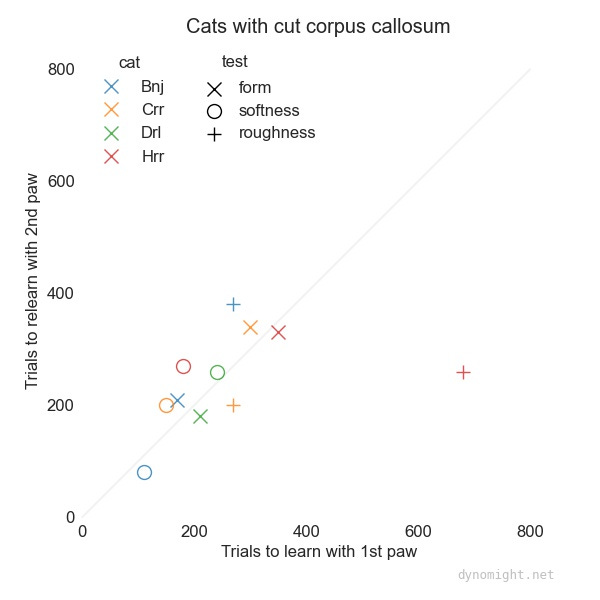

WHAT THEY WANTED TO TEST. Do similar results hold if you use touch rather than vision?

WHAT THEY DID. They took eight cats and cut the corpus callosum of four. One cat (Hrr) also had the optic chiasma cut in the above experiment, but presumably this doesn’t matter since vision isn’t being used. These cats were placed in a box where only one forepaw (right or left) could press two pedals. These varied in either form (prism vs. square) softness (wood vs. rubber) or roughness (smooth wood vs. sandpaper)

WHAT THEY FOUND. Cats with intact corpus callosum could re-learn the same task with the second paw more quickly. In the following plot, x, o, and + marks the different types of tests.

In cat with the corpus callosum cut, however, relearning with the second paw usually took almost as long as learning with the first paw.

Myers 1958

AMA Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 1958

WHAT THEY WANTED TO TEST. Cutting the corpus callosum seems to prevent the other hemisphere from being able to perform the task the other eye was trained on. But is that because the two hemispheres ordinarily make two “copies” of the learned information, or is there one copy with the information shared during testing? Suppose you train a cat while only one hemisphere of the cortex gets any visual information. Then you surgically remove much of the trained hemisphere. Will the other one be able to do anything?

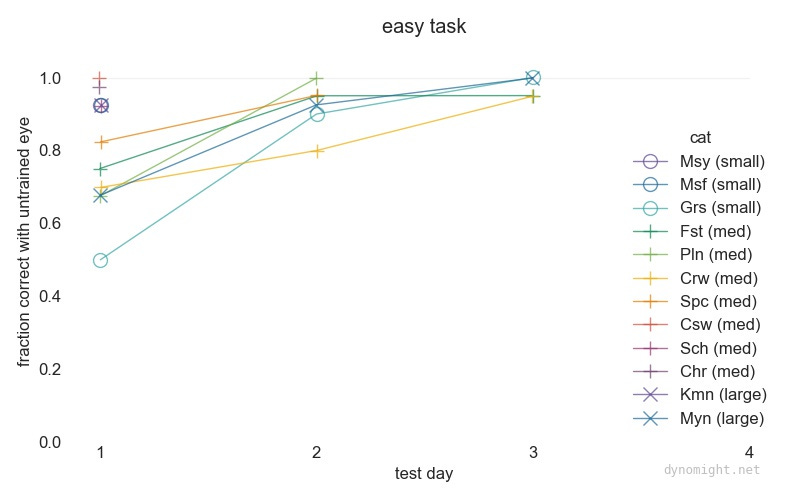

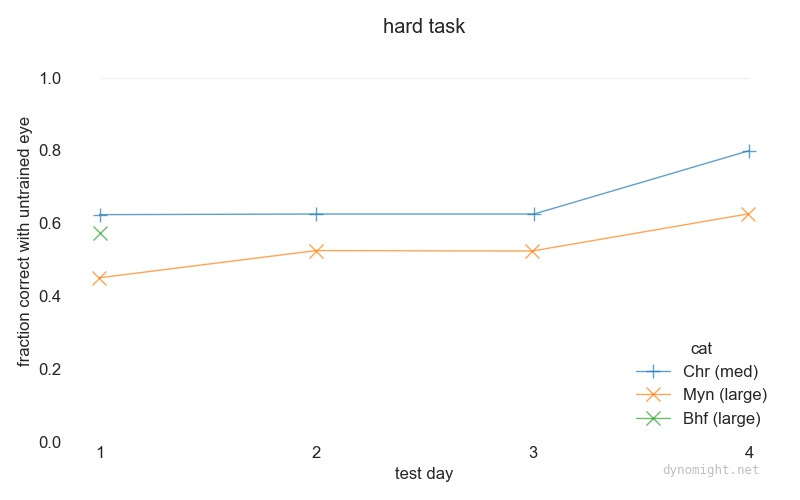

WHAT THEY DID. They took 14 cats and cut the optic chiasm. (They did not cut the corpus callosum.) They then trained them to recognize visual patterns with one eye covered, similarly to Myers 1955. Once they reached a performance of 34/40 trials correct, they got 10 more days of 40 trials. Then, they removed various amounts of the “trained” cortex corresponding to the eye that could see. They did all the tests on two tasks, one “easy” and one “hard”.

After 12 days to recover, they did 40 new tests per day, and recorded how the cats did.

WHAT THEY FOUND. On the easy task, the cats almost all did well within a few days, while on the hard task, there was little transfer. This plot shows the different cats with markers depending on how much cortex was removed.

Here are the results on the hard task.

There are no numbers on how long it took to learn with the first eye but judging from Sperry 1956 it was presumably more than 1-3 days.

Trevarthen 1962

Science, 1962. (Although the actual data below is from Trevarthen’s PhD thesis.)

WHAT HE WANTED TO TEST. The previous experiments train one hemisphere and then test on the other. What if we take a monkey, sever the hemispheres as much as possible, and then show the two hemispheres contradictory things simultaneously? Will these monkeys get less confused than monkeys with intact brains?

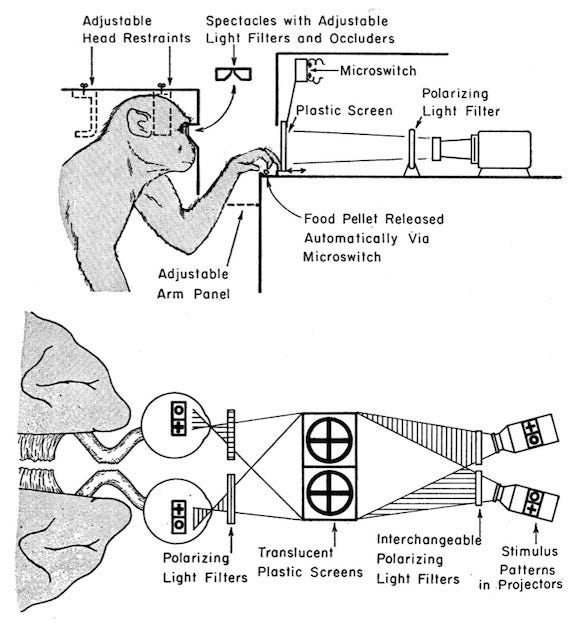

WHAT HE DID. He took two monkeys, and cut the optic chiasm, the corpus callosum, and the anterior and hippocampal commissures. Then, he used polarized glasses to show opposite patterns to the two eyes. For example, the left eye might see +o while the right eye sees o+. The order of the patterns is randomly altered. There were 14 such patterns.

There were two screens in front of the monkey. They would get a morsel of food if they pressed the correct one. For example, the monkey might always need to choose the side that’s + for the left eye and o for the right eye. They repeated these trials in groups of 10 until the monkeys either got 10/10 right or 9/10 twice in a row. Then they switched to doing trials with just one eye, repeated it until the monkey learned it, and finally the other eye.

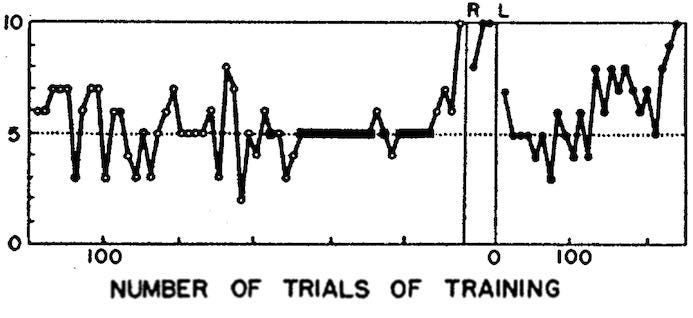

WHAT HE FOUND. The monkeys could always do well with one eye (almost always the right) but sometimes did well with both eyes. Here’s a typical example of the full training process. The main part shows the training period, while R and L show the results of re-training each eye.

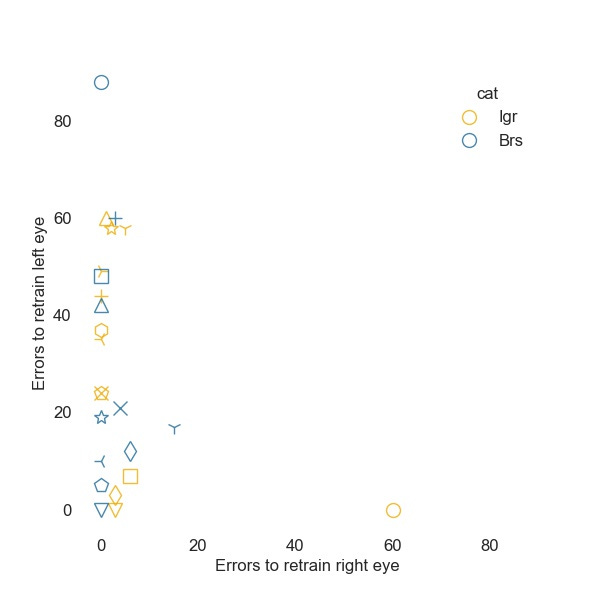

Here are the full results of the number of trials needed to re-train with each eye. The different markers show the 14 different shape patterns that were used.

They tried various patterns and couldn’t easily figure out which would transfer well to both and which wouldn’t. They mention that the two monkeys were similar in which patterns this happened for, though. For tasks involving color or brightness differences, things tended not to transfer to both eyes.

He took two extra monkeys and cut the posterior commissure, habenular commissure, and rostral two-thirds of the quadrigeminal plate. (I think in addition to the other stuff) In these monkeys there didn’t seem to be the “interference” in color discrimination, though there still was in brightness.

Discussion

Obviously, it’s strange that these animals appear to behave normally, even when these tests show they don’t always behave like a single unified system. We even know that humans after similar procedures will explicitly tell you that everything feels totally normal. Still, the whole goal of this article is to avoid injecting personal narrative about what it all means, so I’ll shut up here. It’s much more fun to DIY your own philosophical rambling anyway.

The "reminder about mammal brains" sections begins with the phrase, "the other layer of the brain is the cortex." Is part of this article missing?